30 Images of Wartime America from a Pioneering Female Photojournalist

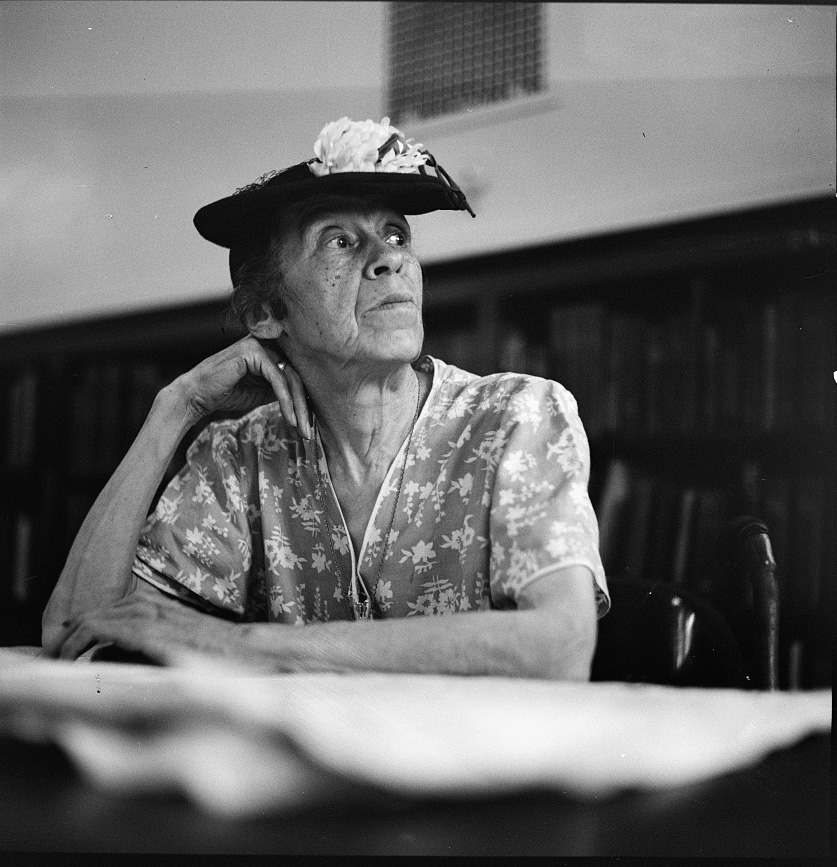

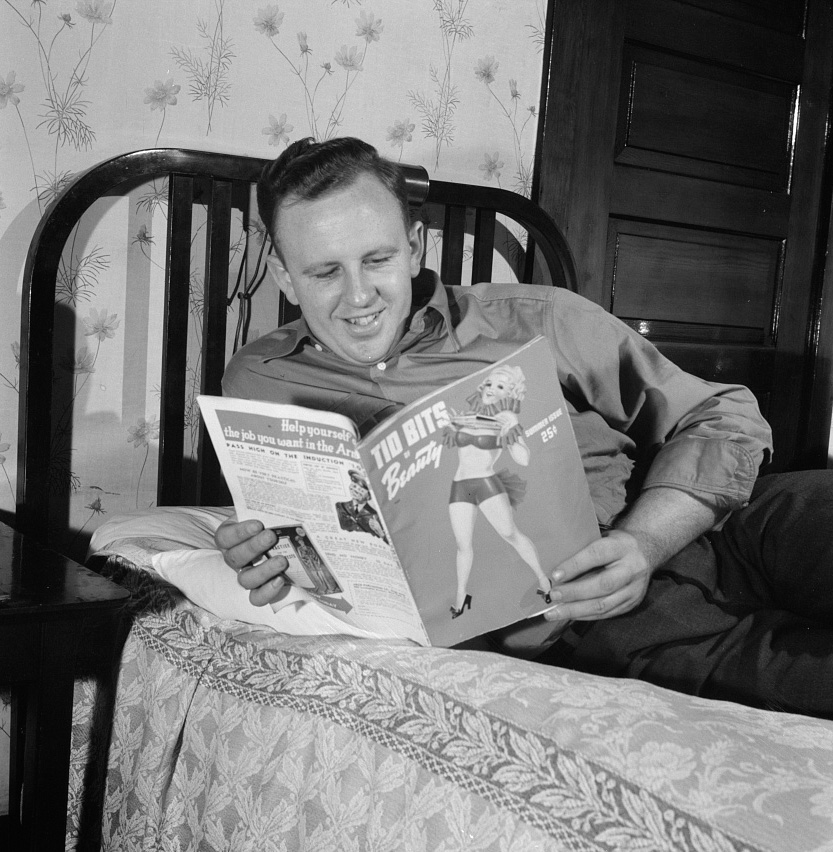

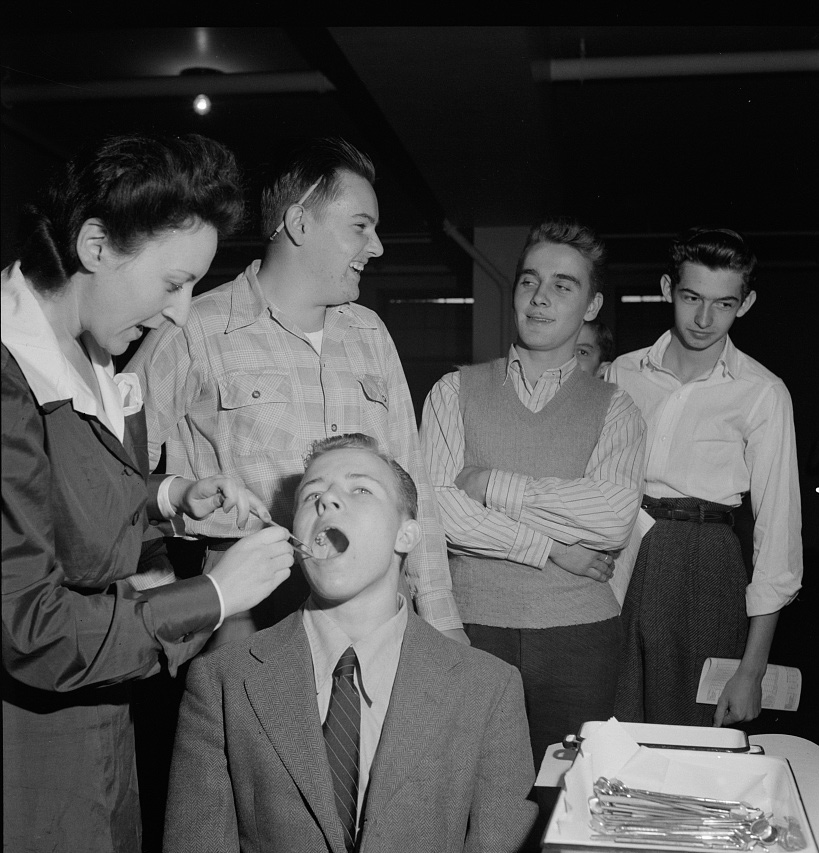

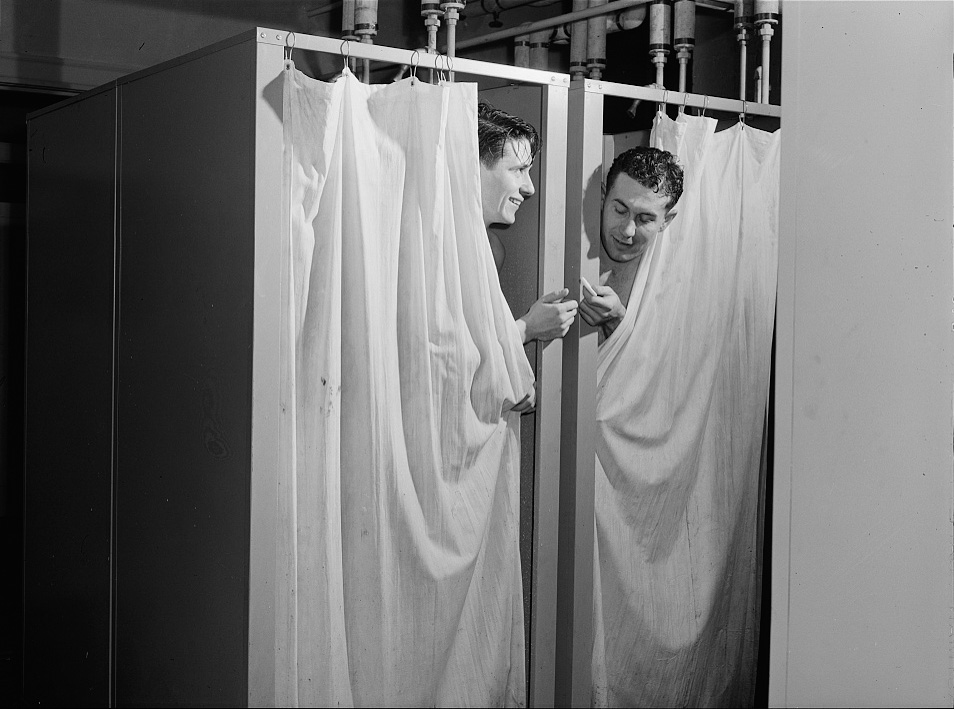

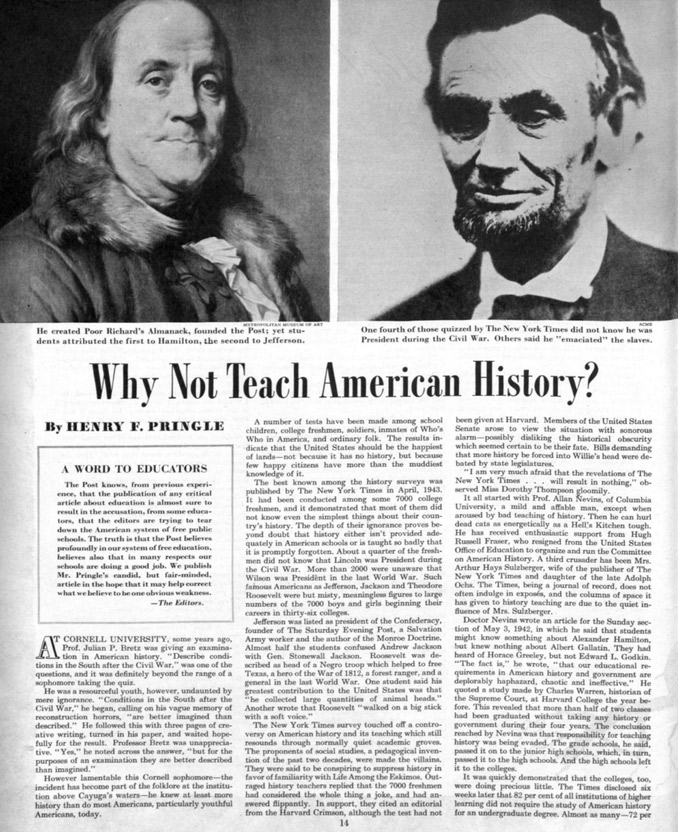

When Life magazine printed its first issue in 1936, the cover featured an austere photograph of the newly built Fort Peck Dam shot by Margaret Bourke-White. In a small town in Wisconsin, a teen girl named Esther Bubley saw that cover and decided that she, too, wanted to become a photographer. Her career would span the pages of the country’s leading magazines — Vogue, Life, The Saturday Evening Post — and send the intrepid photojournalist around the globe capturing hundreds of thousands of photos of people and places in the middle century. Today is the centennial of Bubley’s birth.

Much of Bubley’s work was industrial or commercial — depicting life in company towns for Standard Oil or photographing cute animals and babies for publishing houses. Before she made a name for herself, though, Bubley cut her teeth working as a lab assistant in Washington, D.C. for Roy Stryker, head of the photography project of the Office of War Information.

In 1943, to prove her acumen to her boss, Bubley used her free time to shoot hundreds of images around the city, and she accompanied them with detailed text that documented the stories of high-schoolers, sailors, boardinghouse tenants, and other everyday people in D.C. He quickly sent her on the road to photograph Greyhound riders and workers. Stryker and Bubley left the OWI later that year to work for Standard Oil, and she left more than 2,000 images for the government’s archives.

Bubley documented many facets of the U.S. — and the world — throughout her expansive career. She photographed a series on the Pittsburgh Children’s Hospital; magazine stories on farmers, single mothers, and teenagers; and tens of thousands of images of workers across the world. Writing about Bubley’s work in American Heritage, Nicholas Lemann noted “an effortless equivalence among subject, photographer, and audience.”

Her photography has been featured in several exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art, and she attracted some attention during her life for her oversized role in photojournalism in the 20th century. Still, Bubley’s life and work remain relatively obscure, and her unique eye for capturing the nuances of everyday American life underobserved.

In the following images, selected from her work at the Office of War Information in 1943, Bubley’s skill for documenting an unvarnished portrayal of Americans of various walks of life results in an invaluable record of the period.

The Conspiracy Theory That Spawned a Political Party

Good, Christian American families were whipped into a hysteria over a shadowy, secretive — and possibly even satanic — cabal subverting our nation’s democracy, conspiring against justice, and performing bizarre, blasphemous rituals.

This may sound like a modern, paranoid movement on social media, but it’s actually describing a 200-year-old conspiracy theory in the U.S. that alleged that men in the growing Freemasonry fraternity were engaged in a nefarious plot to exert unchecked control over the republic. The Anti-Masonry movement grew to become the first “third party” in the country’s history, permanently altering American politics during a transformative political realignment that would see new parties, ideals, and democratization of the U.S. system.

The spread of Anti-Masonry and its attendant conspiracy theories were aided by the simultaneous religious revivals sweeping across the states, and the movement’s transference into the political sphere met with other opponents of Andrew Jackson. But an important aspect of this conspiracy theory has often been overlooked: it began in reaction to an actual conspiracy.

No other modern historian has spent as much time digging into the history of Anti-Masonry as Kathleen Smith Kutolowski. Born and raised in a small town in Genessee County, New York, she collected otherwise untouched Masonic data from the region, offering a more complete picture of 1820s New York and demystifying the period of supposed hysteria.

Kutolowski’s father belonged to a Masonic lodge. When she began writing her dissertation on the general political development of the area in the 19th century, she says, “I kept running into Masons as political leaders, right down to candidates for county coroner.” She analyzed the records of Genessee and nearby counties and found that Masons were not necessarily the upper-class elites that many had thought; they came from a variety of backgrounds, economic statuses, and denominations.

This was in line with her discovery that there were many more Masonic lodges in Western New York than anyone else had cared to document.“Masonry was a more widespread phenomenon than people understand, and they dominated political office,” she says.

In the 1820s, Freemasonry enjoyed explosive growth in cities, towns, and even small villages in the Northeast. Tens of thousands of Masons had established hundreds of lodges in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, and they held “influential civic positions out of proportion to their numbers,” according to Kutolowski’s research. Many of the founding fathers, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, had been Masons. In New York especially, Masons held power. But the popular movement against them arose because of the ways they wielded it, particularly in Genessee County in 1826.

That summer, a man named William Morgan announced his plans to publish a sort of Freemasonry tell-all with the Batavia Republican Advocate publisher David Miller. Morgan had attended some local Masonic meetings and claimed to be a longtime member, although the latter was unsubstantiated. His exposé was to be called Illustrations of Masonry, and the Masons at the Batavia lodge became obsessed with stopping him.

They began to harass Morgan and Miller. The sheriff of Genessee County, a Mason, complied with his fraternity and arrested Morgan several times on petty debt charges. Another gang of Masons attempted to ransack and set fire to Miller’s offices. In September, Morgan was sitting in jail in Canandaigua when a stranger bailed him out. Upon release, the writer was ambushed by several Masons and forced into a closed carriage. They drove him to Fort Niagara, and he was never seen again.

Most historical analysis of Anti-Masonry focuses on Morgan’s disappearance as a fairly simple explanation for the birth of the movement, but Kutolowski explored the circumstances around the incident more thoroughly, saying, “The important event was not necessarily the kidnapping itself, but the cover-up that followed.”

Though Morgan’s kidnapping and (likely) murder were an outrage, the Masonic subterfuge that was to come would only exacerbate any extant public perceptions that the fraternity posed a legitimate threat to freedom.

For more than four years, trials and grand jury investigations kept the “Morgan Excitement” in the news and on Americans’ lips. Dozens of Masons were eventually indicted, but not without obstruction from Freemason police officers, politicians, lawyers, doctors, and clergy. Once-Mason and well-regarded New York publisher William Leete Stone thoroughly documented every moment of the Morgan affair at the time in his Letters on Masonry and Anti-Masonry … , maintaining that “the men engaged in this foul conspiracy, thus terminating in a deed of blood, belonged to the society of Freemasons.” Stone tracked the indignant public protest and subsequent legal action over Morgan’s disappearance, but, as he wrote, “they soon found their investigations embarrassed, by Freemasons, in every way that ingenuity could devise.” In the Genessee grand jury trials of 1826-27, five of the six foremen were Masons, including one who was implicated in the scandal. The juries — picked by sheriffs at the time — were full of Masons, or their brothers or sons, and the few Masons who spoke out against the fraternity’s militant protection of its own were expelled from their lodge. Similar circumstances stalled or obstructed justice in Ontario County trials as well.

While the obvious perpetuation of injustice at the hands of Masons generated plenty of reasonable Anti-Masonic sentiment, the more fervent among the movement spun irresistibly fascinating webs of accusations against the fraternity. Kutolowski says that “protest did not leap full-blown from the kidnapping to beliefs about Satanic conspiracies,” but a market for the latter seemed to open up nonetheless.

Morgan’s manuscript was published a few months after his disappearance, and, while it offered an abundance of detail on Masonic practices, the book failed to live up to its sensational promise as “a master key to the secrets of Masonry.” It was soon eclipsed by legions of articles, books, speeches, and entire Anti-Masonic periodicals that disclosed — often fallacious — claims regarding the fraternity’s evils.

In Danville, Vermont, the local paper North Star (not to be confused with Frederick Douglass’s publication of the same name) published a message from the Genessee Baptist Convention in 1828: “That Free Masonry is an evil, we have incontrovertible proof; and this appears from its ceremonies, its principles, and its obligations.” A few months later, the Star reprinted (from Morristown, New Jersey’s Palladium of Liberty) one Mason’s “renunciation” from Freemasonry, colorfully painting the fraternity’s membership as men “whose hands reek with the blood of human victims offered in sacrifice to devils, or who worships a Crocodile, a Cat or an Ox.” Such dramatic renunciations by supposed ex-Masons were regular fixtures in Anti-Masonic papers, and lists bearing the names and towns of recent Masonic renouncers often accompanied them.

An 1831 issue of Vermont’s Middlebury Free Press featured a fictionalized dialogue between the mythic demons Belphagor and Beelzebub in which they boast of their Satanic sway over Freemasonry (“That bulwark of our empire on earth!”) and delight in their ungodly machinations against the republic (“ — that post, well-fortified, in our enemy’s country, from whence, at pleasure, we may make successful inroads upon his friends and people!”) .

Anti-Masonic fervor wasn’t contained to printed communications; it manifested in real-world violence as well. Though Freemasons had traditionally marched in annual St. John’s Day parades, their celebration in Genessee County in 1829 was met with Anti-Masons who threw rocks at them. Then, protesters ransacked a Royal Arch Chapter headquarters. Freemasons were spooked — particularly those in Genessee County, where 16 of the 17 lodges and two chapters soon dissolved. But for many Anti-Masons, public renunciations and even dissolution of local Masonic charters was not enough. They held that Freemasonry must be abolished, that its mere existence — even if it was weakened and relegated to the shadows — was proof that their work was yet unfinished. Wilkes-Barre’s Anti-Masonic Advocate expressed as much in 1832: “To overcome this evil is a work of intelligence, and a work of time. We have scotched the snake, not killed it. We have forced it to hide in darkness — but though unseen, it is not less dangerous.”

Anti-Masonry’s entrance into electoral politics was swift: the spring after Morgan’s kidnapping saw Anti-Masonic candidates for office in Genessee County. “Their level of organization was amazing,” Kutolowski says, “right down to school district committees, taking a social issue to the ballot box.” Since Anti-Masons viewed the fraternity as an existential threat to the budding country’s republican values, they turned to grassroots democratic mobilization to uproot it.

The Anti-Masonic Party grew into a national force vying for power up and down the ballot in the 1830s. It was the first such third party in the country, dwarfed by the National Republican Party (later the Whigs) and the Democratic Party. The Anti-Masonic Party held the first presidential nomination convention of any political party in U.S. history in Baltimore in 1831, choosing former U.S. Attorney General William Wirt for their ticket. Wirt garnered more than 100,000 votes (almost eight percent of the popular vote) and won the sole state of Vermont in the 1832 election. The party also elected Vermont’s governor along with plenty of local and state seats, but it fizzled out over the course of the decade.

The question of the Anti-Masonic Party’s legacy is anything but settled among political historians. Was it all a righteous democratic force for justice or a cynical conspiracy cult? Many have cast the Anti-Masonry movement as a right-wing reactionary one, citing the economic angst and ardent religious character of its adherents. Although “its witch hunting disrupted churches, families, and communities,” Anti-Masonry had a negligible effect on American politics, according to Donald J. Ratcliffe.

But two-time Pulitzer-winner Richard Hofstadter, writing on the “paranoid style” of American politics in Harper’s in 1963, allowed that Anti-Masonry “was intimately linked with popular democracy and rural egalitarianism.” Other histories have also credited the Anti-Masons for enshrining democratic processes as a populist force for “equal rights, equal laws, and equal privileges.” Author and historian Ron Formisiano examines the populist aspects of Anti-Masonry in his book For the People … . He says that Anti-Masonry has received similar unfair treatment as other American third parties in the 19th century, reduced to “movements of bigotry” without consideration for the complexity therein. He claims the Know Nothing Party is similarly derided and misunderstood in modern times in spite of its connection with important, democratizing reforms.

The kneejerk labeling of Anti-Masons as religious zealots and reactionaries has met resistance as historians like Kutolowski have more closely examined the circumstances around the movement.

Kutolowski says the Anti-Masonry movement had “an enormous role in the development of American political culture.” In addition to pioneering democratic political party operations like the national nominating convention, Kutolowski points to the party’s championing of reforms like making kidnapping a felony and ending the appointment of jurors by sheriffs, as well as their backing of economic goals that would become mainstream, like antitrust laws. After its dissolution, much of the movement’s supporters would turn to the cause of anti-slavery.

With regard to the Anti-Masons’ primary goal — the complete abolition of the fraternity — they were, of course, unsuccessful. Though the reputation of Freemasonry was tarnished for decades, Mason lodges still operate in the U.S. and around the world. Masonic history of the Anti-Masons has often cast the phenomenon as a paranoid, discriminatory crusade. Even in recent years, members of the “ancient and honourable order” have occasionally decried public “misconceptions” about their organization, namely regarding the inconsistent inclusion of women among lodges.

The popular movement against Masons is long over, but in the age of social media — one in which virtually any conspiracy theory can take root — anti-Mason rhetoric is still out there. The charges leveled against Masons indiscriminately by internet users are much more complicated than those out of Western New York a few centuries ago. Conspiracy theorists on social media have woven anti-Masonic theories into the lore of “QAnon,” along with many other theories regarding a cabal of satanic, cannibalistic pedophiles and the Trump administration’s heroic crusade against them. Such posts might call attention to Masonic-seeming symbols in photographs of the British royal family or in the logos of Gmail or government seals. The implication is that Freemasons (along with Illuminati, Hollywood, Democrats, and Jews) exert far-reaching influence in government and culture and hint at their schemes with cryptic numerology. Recent studies have documented enormous spikes this year in social media users spreading the baseless QAnon theory, leading to several platforms taking steps to remove such content.

Kutolowski has not followed much recent news about QAnon or current conspiracy theories around Freemasonry, but she says they could be with us for a long time. She is adamant that the Anti-Masons of the 1820s and ’30s — unlike Pizzagaters and QAnons — have been branded unfairly as wacky conspiracy theorists by historians and journalists. She recalls the words of an Anti-Masonic town leader, defending the veracity of their cause: “All the evidence of historic demonstration will be necessary to convince those that come after us that the record is true.” But, as Kutolowski’s work might demonstrate, the existence of such evidence is not necessarily enough; someone must be willing to seek it out.

Featured image: “The Lord’s Prayer of the Freemasons,” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, 1870 and Illustrations of Masonry, Utah Lighthouse Ministry, 1827

America’s School Nursing Crisis Came at the Worst Time

On a recent episode of the podcast RN-Mentor, Robin Cogan gave a less-conspicuous perspective on the current push for schools across the country to return to in-person learning: that of a school nurse. “When I look at opening schools,” she said, “and I’ve been very entrenched in it both at the state level and at the local level — it feels to me like we’re doing the biggest social experiment ever without an IRB [institutional review board] … our hypothesis: we are going to have kids and staff that are sick and, God forbid, die.”

Cogan, a Nationally Certified School Nurse from New Jersey, writes the blog Relentless School Nurse, where she’s been sharing useful information as well as stories from school nurses around the country. One has been tasked with providing their own personal protective equipment. Another spoke out against her school’s reopening plan in Georgia and resigned from her position. Cogan’s recent posts have revolved around a central theme: “It Has Taken a Pandemic to Understand the Importance of School Nurses.”

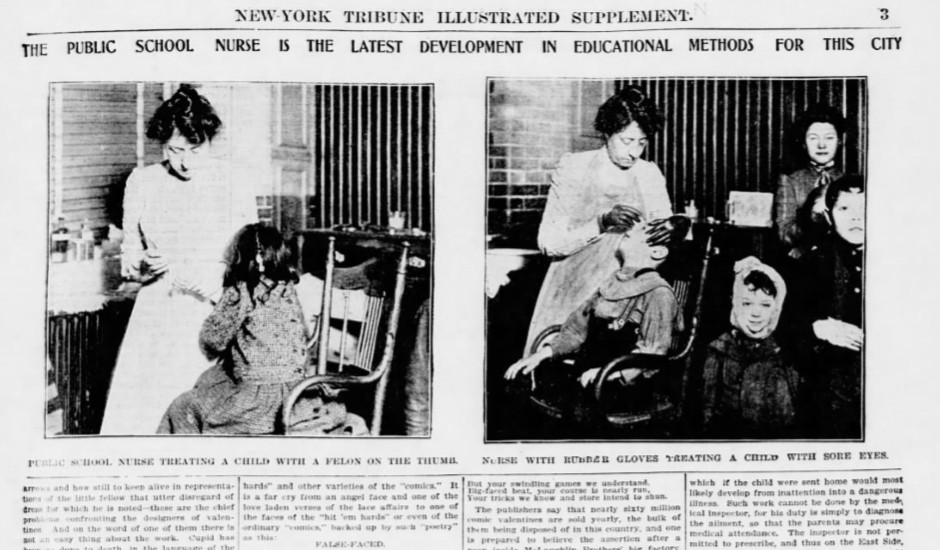

Around a century ago, school districts around the country were just coming to realize the value of adding a nurse to their ranks. In newspapers from Sacramento to Bloomington, Illinois to Washington, D.C., stories applauded school boards for often-unanimous decisions to budget for school nurses.

In 1918, The Charlotte News reproduced an entire paper read by a Miss Stella Tylski at a P.T.A. meeting: “There can be little doubt, that as the work of the nurse becomes better understood, there will be a greater demand all over the world for her services in the schools, for wherever she has made her entry, her value has been recognized.”

At some point in the last 100 years, however, school nurses fell off the list of public school priorities. In recent decades, many school districts have been eliminating qualified school nurse positions. According to a 2017 study from the National Association of School Nurses, less than 40 percent of schools employ a full-time nurse. In the western U.S., it’s only 9.6 percent. Twenty-five percent of American schools don’t even have part-time nurses.

As health considerations have taken center stage in conversations around education, it’s difficult to imagine a responsible plan for returning to school during a deadly pandemic that doesn’t include an on-site medical professional. Yet, for many of the country’s strapped schools, that may seem to be the only option.

Since its inception, school nursing has been predicated on public health.

School nursing in the U.S. began as a sort of experiment. At the turn of the century, when cities were becoming crowded with unsanitary slums that beckoned reform, public schools faced attendance problems stemming from influenza, tuberculosis, and skin conditions like eczema and scabies.

Although the New York Board of Health performed routine medical inspections of the city’s schools — and sent home children with troubling symptoms — there wasn’t a system in place to ensure students would recover properly. In 1902, The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by nurse Lillian Wald, pioneered a program to place one nurse in four city schools — with around 10,000 students total — for one month.

The nurse was Lina Rogers, and her undertaking was a significant one. She was to perform her nursing duties at each school with makeshift facilities. At one school, she had only a janitorial closet as an office and an old highchair and radiator as examining furniture. At another, she treated students on the playground. “When children found out that they could have treatment daily and remain in school,” she wrote, “‘sore spots’ seemed to crop up over night.” Perhaps most importantly, Rogers made visits to students’ homes to discuss their ailments and treatment with their parents. She found it difficult, but necessary, to demonstrate medical care and explain the importance of hygiene in preventing illness.

At the end of the Henry Street Settlement’s month-long experiment, Rogers was appointed to lead a team of school nurses in the city. The month before she started in schools, the city saw more than 10,000 absences in a month. One year later, the number of absences for the month was 1,101.

Rogers became a chief advocate for school nursing, and cities across the country noted the Henry Street Settlement’s success. In 1908, The Spokane Press, among many others, applauded the New York school nurses for improving their city’s school attendance and “converting the truant into a studious pupil.”

Rogers wrote a textbook in 1917 detailing her work and giving guidance to the nation’s women who were setting out on this new occupation. She found the presence of health professionals in schools to be a vital aspect of public education’s mission to prepare American children for happy and healthy lives, but she recognized the tall order of staking the health of a community on one position. As she visited students’ homes, she found that things other than illness were keeping them from school, such as babysitting, housework, street crime, and neglect. “So the field of vision of the school nurse rapidly widened,” she wrote. “It was easy to see that if the school children were to be given even a fair opportunity of preparation for life’s work and duties, many things in the social life of the homes had to be improved. All the social problems of humanity, problems as old as the world, face the school nurse at the threshold of her work.”

Throughout the postwar years and the Great Society programs of the 1960s, school health programs were expanded to address drug abuse, students with disabilities, and mental health, among other public health inequities. School nurses became iconic fixtures of American schools, tasked with identifying and treating rising chronic illnesses.

But after the recession of 2008, school funding took a hit. Most states cut funding to education, and much of those losses have yet to be fully recovered. Since school nursing programs rely on school budgets — and few states mandate them — they’ve been quietly eliminated, consolidated, or replaced by untrained employees for years. Less than one-third of private schools employ any kind of school nurse at all.

American school nurses still find themselves advocating for public health amid dire circumstances. Most of them are paid less than 51,000 dollars per year, and the prospects of career mobility in the field are stark. A University of Pennsylvania study found that 46 percent of school nurses were dissatisfied with their opportunities for advancement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, nurses could be among the most important figures at any school.

In a phone call, the president of the National Association of School Nurses, Laurie Combe, mentioned that the first swine flu outbreak was discovered by a school nurse in 2009: Mary Pappas of Queens, New York. “We have expertise in collaborating with health departments to identify, record, and manage communicable diseases in schools,” she said. “We’re the public health practitioners closest to communities on a daily basis.”

According to Combe, nurses are a vital position in any school. She says they have, in many cases, already been working with schools on emergency operations planning. Throughout this pandemic, school nurses have informed their schools on the safe dissemination of food — to families who rely on free and reduced lunches — and technology and educational materials. They’ve continued to make sure students have access to their health providers and medications, as well.

“When schools don’t have the public health and infection control expertise of school nurses, they’re at risk of mismanaging the proper procedures. They risk mixing well children with those who might be symptomatic of COVID-19,” Combe says. “We know that when school teachers have to direct their time to managing health conditions, there is a loss of instructional time, principals lose administrative time. If students are unnecessarily dismissed, parents may lose wages. There is a cross-sector loss of time and money when there is not a school nurse present.”

Combe says the precautions that schools need to put in place in order to reopen during the pandemic are costly, like facility improvement, personnel, and PPE. The NASN is calling on the federal government to direct 208 billion dollars to support schools’ needs. “If schools are essential to reopen the economy,” she says, “then schools need the same financial support as businesses.”

The question of when it is safe for schools to reopen has different answers for different parts of the country, since schools are experiencing the burden of the virus at varying degrees. Cogan writes, “The bare minimum that we need to safely reopen schools is a stable, low rate of COVID-19 in the community [about 5 percent]; funding for and availability of basic public health precautions … and access to testing for students and school staff.”

In the midst of the most drastic public health crisis of our time, the forgotten heroes of our schools may prove to be an imperative component to our national recovery. If it did “take a pandemic to understand the importance of school nurses,” then perhaps that national lesson will endure this time around.

Featured image: American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress), July 1921

The First Black U.S. Senator Argued for Integration after the Civil War

Despite a days-long outcry from Democratic senators attempting to block the first African-American member of the U.S. Congress from taking his seat, Hiram Rhodes Revels was finally voted in to the Senate along party lines 150 years ago today.

Revels had been appointed to his seat by Mississippi Republicans, as senators at the time were selected by the state legislature instead of by popular vote. Revels had served as an alderman in Natchez, Mississippi, having settled there after traveling the country as a minister, educator, and chaplain for the Union army. When he arrived in Washington, D.C. to be sworn in, Revels was met with protest from the minority Democrats.

“There was not an inch of standing or sitting room in the galleries, so densely were they packed,” according to The New York Times, “and to say that the interest was intense gives but a faint idea of the feeling which prevailed throughout the entire proceeding.” An atmosphere of fervent argument erupted in the chamber in those few days of deliberation over whether or not to allow the first black senator into the body, but the Times only hints at the insulting, racist language hurled at Revels and his defenders.

The official argument used against Revels was that he had not been a U.S. citizen for the nine years required to be eligible for the U.S. Senate. Even though Revels was born a free man — in 1827 — Democratic senators argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 had given the Mississippi alderman only four years of citizenship. Several Republicans held that this was an absurd argument, and that the Senate ought to vote Revels in and begin a new age of representation for African Americans. Democrats accused them of “hollowness and insincerity” for the causes of black men, claiming Republicans were only looking after “partisan considerations.”

In the late afternoon, on February 25th, the vote was taken, and Democrats lost, 48 yays to 8 nays. The Times credited Revels for remaining dignified even though “the abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of anyone.” He took an oath of office, took his seat, and the Senate was adjourned for the weekend.

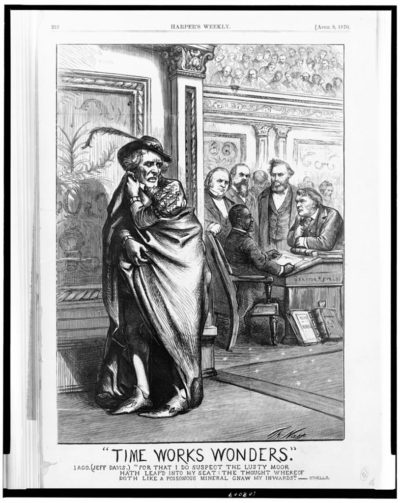

Of the two Mississippi Senate seats filled in that session, one had been most recently occupied by Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon by Thomas Nast that featured Davis as Iago, the traitorous villain of Shakespeare’s Othello, looking on at Revels taking his place in the chamber: “For that I do suspect the lusty moor hath leap’d into my seat: the thought whereof doth like a poisonous mineral gnaw my inwards.”

Revels only served in the U.S. Senate for about a year. Toward the end of his term, on February 8, 1871, Revels sat on the Committee on the District of Columbia as it heard arguments over a clause that would have effectively desegregated D.C. schools. Senator Revels addressed the committee, arguing against an amendment to strike the clause, saying, “If the nation should take a step for the encouragement of this prejudice against the colored race, can they have any ground upon which to predicate a hope that Heaven will smile upon them and prosper them?” He spoke about the oppression of African Americans all over the country that continued because of segregation in housing, church, transportation, and education, and he pleaded his fellow senators to consider how desegregated schools could help to empower African Americans “without one hair upon the head of any white man being harmed.” Unfortunately, his side lost the vote, and school segregation remained lawful in Washington, D.C. until 1954.

Revels was the first in a small wave of black southern congressmen during the Reconstruction Era. A few years after his term, another African American — Blanche Bruce — was elected to the Mississippi Senate. Bruce was able to serve a full term, but Mississippi hasn’t elected an African-American U.S. senator since. In fact, only ten have served in the history of the country.

Featured image: Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve as a U.S. senator. (Library of Congress / Brady Handy Photograph Collection)

A History of Hating the Rich

Billionaires are a threat to democracy.

Most rich people got rich by taking advantage of other people.

Wealth should be taken from the rich and given to the poor.

Those are a few statements on which most people can agree — most people under age 30, that is, according to the Cato 2019 Welfare, Work, and Wealth National Survey.

A few days ago, the Academy Award for Best Picture went to a foreign language film for the first time in Oscar history. The Guardian calls Parasite, a Korean comedy-thriller, “a searing satire of a family at war with the rich,” and the subtitled film saw unexpected popularity in U.S. theaters. Simultaneously, a presidential candidate who stakes his campaign on a fight with billionaire oligarchs has just taken the lead in national poll averages for the Democratic primary race.

This country has always had a precarious relationship with its super-wealthy. The richest rich have, at various points in history, filled Americans with fascination or anger. Lately, a trend toward the latter is evident, and it follows a long tradition of distrust of the upper crust.

Sometimes, the historical parallels of American attitudes toward wealth reveal themselves in subtle ways.

Last March, then-presidential candidate and entrepreneur John Hickenlooper appeared on MSNBC’s Morning Joe to talk about his presidential bid. Host Joe Scarborough commended Hickenlooper’s business success as “an advertisement for American capitalism” and asked the candidate if he was a proud capitalist. When Hickenlooper evaded the question, decrying the label, Scarborough asked twice more — visibly losing patience each time — if the small business man would even consider himself a capitalist.

Larry Glickman, a professor of history at Cornell University, says he has used this clip in one of his classes to illustrate the criticism of so-called robber barons of the late nineteenth century: “In the Gilded Age, ‘capitalist’ was really a term given by its enemies to people who had earned wealth in an unfair, immoral way, so a lot of small business men said something similar to what Hickenlooper said.” Glickman says the distrust of robber barons (or capitalists) comes back to the question of hard work. “There was this idea that you had labor producing things, and that accumulating wealth through honest production was a good thing,” he says, “but there was a new class of people called capitalists getting their wealth through unproductive, exploitative ways.”

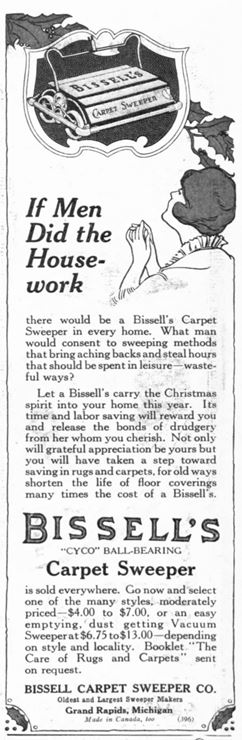

British economist John Stuart Mill referred to this kind of wealth — in the mid-19th century — as the “unearned increment.” Divine right was un-American, but passive income was filling the wallets of a select few in the country while farmers and workers struggled. Men like Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller acquired hundreds of millions of dollars in the 19th century by building monopolistic empires and strong-arming competition (and their own workers) into submission.

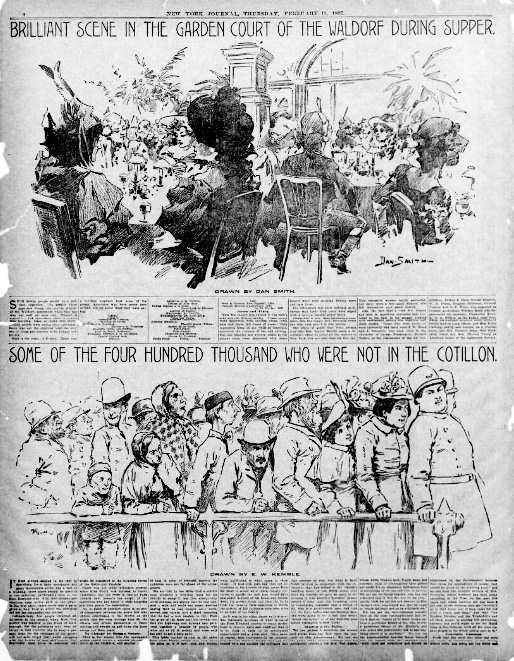

It was against this backdrop of economic disparity that heiress Cornelia Bradley Martin decided to stage an exclusive gathering for the country’s financial elite.

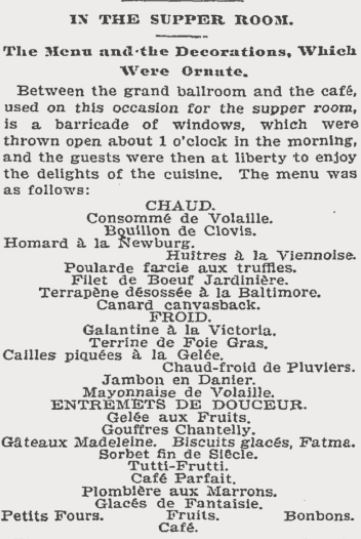

In 1897, the New York socialite hatched an idea for a costume ball in the Waldorf Hotel that she hoped would be the most extravagant party in the nation’s history. With thousands of orchids and roses, rare tapestries and velvet canopies, and terrine de foie gras, Cornelia would dress as Mary, Queen of Scots, while her husband played a member of Louis XV’s court. Hundreds more of the rich elite would turn up dressed mostly in historic royal garb, like the dozen Marie Antoinettes who, perhaps, had forgotten about the queen’s fate.

At St. George’s Episcopal Church in New York, where the congregation included the likes of J.P. Morgan, the clergyman warned his flock against attending Mrs. Bradley Martin’s ball: “Never were the lines between the two classes — those who have wealth and those who envy them — more distinctly drawn … Such elaborate and costly manifestations of wealth would only tend to stir up widespread discontent.” When the night came, hundreds of policemen — led by Theodore Roosevelt — closed the sidewalks outside the Waldorf to pedestrians to make way for the giant dress-up party.

Newspapers around the country, and even many society people, criticized the ostentatiousness (or plain stupidity) of the ball. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers’ Monthly Journal wrote, “The Bradley Martins are said to have spent $300,000 … which would have made glad thousands upon thousands of the poor of New York who are struggling in abject poverty, was used up in some five or six hours of the grossest exhibition of the arrogance of wealth America has ever witnessed.” The host and hostess were puzzled by all of the bad press, since they believed their event had stimulated New York’s economy. After all, “many New York shops sold out brocades and silks which had been lying in their stock-rooms for years.”

Meanwhile, New York’s tenements were filled with people living in crowded, unsanitary apartments, as evidenced by Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives in 1890. Poor and immigrant children worked long hours at factories, and families slept together in rooms stacked with beds.

As the various lower classes grappled with the complications of Victorianism receding, a vocabulary for condemning the lavishness of the rich was taking shape. In 1899, Thorstein Veblen wrote The Theory of the Leisure Class, a groundbreaking volume of social and economic criticism that explained the extravagances that had emerged, as well as the phenomenon of “conspicuous consumption,” in industrial societies. “The possession of wealth confers honour; it is an invidious distinction,” Veblen wrote.

That same year, the pages of this magazine recorded the details of the still-excessive lives of New York society, particularly the new set that had grown accustomed to fancy evenings out every night of the year: “Take the dinner with its costly delicacies, wines and flowers, at so much per head; add to that a seat in a portière box at the opera afterward; and go on to the ball or cotillion where the money lavished upon decorations, music, supper at little tables, toilettes and jewels represents an aggregation of opulence almost incredible to the outsider.”

It wasn’t always like this, though, according to the author, Mrs. Burton Harrison, a genteel woman who had lived through the Civil War: “Quiet people who recall the New York of earlier days, and shared in its social diversions then as now, may well stand back in astonishment at our swift advance in luxury.” Mrs. Harrison felt the great wealth accumulation of society families, like the Bradley Martins and the Vanderbilts, was acceptable, even if it had “in theory, no right to exist in an overgrown democracy,” but she believed Americans would adore their burgeoning aristocracy: “our people are fain to give it more deference than the English, or any of the Continental European peoples, bestow on even their reigning family.”

But Mrs. Harrison’s ruby-colored spectacles must have prevented her from seeing the writing on the wall. With the coming Progressive Era, populist politics were on the rise and disdain for the “upper ten” was taking hold across the country.

Historian Michael McGerr wrote in A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America:

By choice and by necessity, America’s social classes lived starkly divergent daily lives and invoked different and often conflicting values to guide, explain, and justify their ways of life. The classes held distinctive views on fundamental issues of human existence: on the nature of the individual: on the relationship between the individual and society.

The Progressive Era brought reform that curbed some excess wealth and confronted corruption around the country, but, as McGerr makes clear, the individualist philosophy behind the Carnegies’ and the Rockefellers’ rise to wealth and power persevered.

Likewise, glimpses into the daily lives of the one percent still provoked amusement and ire.

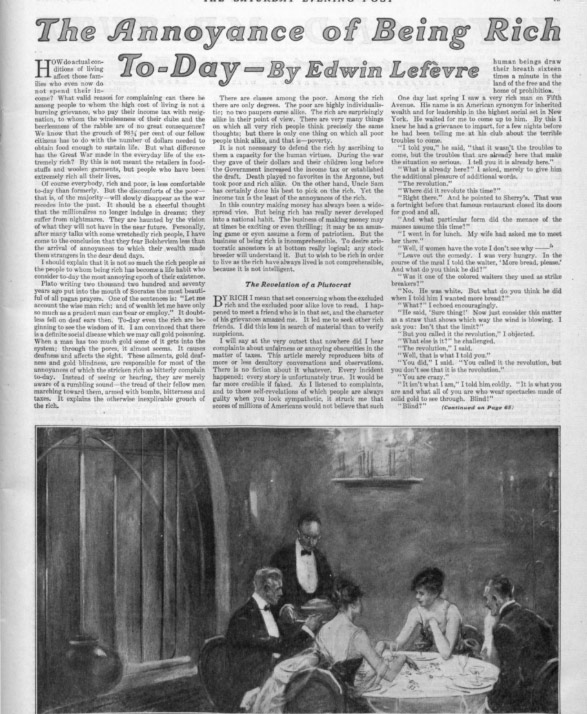

In 1920, Wall Street reporter Edwin Lefèvre derided “some wretchedly rich people” in a Post article called “The Annoyances of Being Rich Today.” Without naming names, Lefèvre detailed conversations with bankers and heirs about their gripes with imperfect service and ungrateful butlers. One rich man told the author that he feared a revolution was afoot after he asked a waiter for bread and — instead of silent obedience — the response came: “Sure thing!” Others complained about accusations of vanity or the prospect of their service staff seeking higher wages.

Lefèvre sums up the groans of the plutocrats by casting wealth as a sort of illness:

I am convinced that there is a definite social disease which we may call gold poisoning. When a man has too much gold, some of it gets into the system; through the pores, it almost seems. It causes deafness and affects the sight. These ailments, gold deafness and gold blindness, are responsible for most of the annoyances of which the stricken rich so bitterly complain today. Instead of seeing or hearing, they are merely aware of a rumbling sound—the tread of their fellow men marching toward them, armed with bombs, bitterness, and taxes.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, even after having seen financial success, wrote about the illnesses of wealth. In his 1926 novel The Rich Boy, Fitzgerald describes the spiritual corruption of the rich, how “they are different from you and me,” and how “they think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves.”

Historian Larry Glickman says there is a tradition of suspicion of great wealth because “there is a feeling that at least some of that wealth did not emerge from honest labor but by illegitimate means.” He says this suspicion remains in the background of American life until it is pushed into prominence in a forceful way every couple of generations or so, sometimes because conditions become unbearable for people who are not rich.

Glickman says the Occupy movement and the subsequent Bernie Sanders campaigns have been a somewhat delayed reaction to decades of rising wealth inequality. What follows, historically, is something like a “rich man’s panic” or “elite victimization,” Glickman says, over calls for a more level playing field, like progressive taxation. In 2014, businessman Tom Perkins warned of a “Progressive Kristallnacht” over what he called The San Francisco Chronicle’s demonization of the rich. Although he apologized for the Nazi reference, other billionaires have publically renounced so-called class demonization.

But as long as extreme wealth continues to accumulate among America’s elite, the young and indebted may always see the complaints of the one percent as mere groans from the costumed aristocracy of a nonstop masked ball.

Featured image: Illustration from “How to Live on $36,000 a Year” by F. Scott Fitzgerald from the April 5, 1924, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, ©SEPS

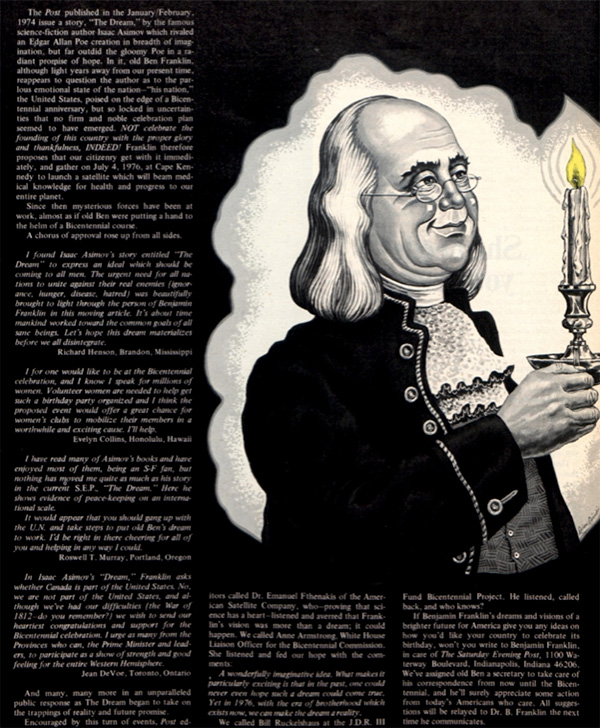

Isaac Asimov’s Conversations with Ben Franklin

Spanning time and space, the fictional worlds of scientist and prolific writer Isaac Asimov imagine alternative realities. Ones in which scientists and engineers resolve galactic struggles and robots walk among people.

Asimov also expressed concerns with the real world in his nonfiction writing, as in 1971 when he proposed — in this magazine — that the United States ought to make the long-overdue transition from its imperial system of measurement to the one utilized by most other nations. “Sanity is the metric system!” he railed, challenging his readers to attempt to memorize the convoluted conversions and calculations required to keep up the pigheaded American tradition of inches and pounds.

Today is the 100th anniversary of Asimov’s birth, and his writings display deep admiration, and tough love, for the country the Russian immigrant made his second home.

In addition to his arguments for reason in the way of official measurement and his musings on extraterrestrial life, Asimov imagined a series of conversations he might have with the founding father (and founder of The Saturday Evening Post) Benjamin Franklin. His most popular writings in the Post were a series in 1974 that depicted somnambulant run-ins with a ghostly Ben Franklin, starting with “The Dream.”

In Asimov’s story, Franklin is delighted to hear about the technological advancements of the modern era, and he excitedly learns the news that his nation is about to celebrate its bicentennial. Though the details of radio communication and television are difficult to conceive, Franklin is most bemused by his country’s failure to bring about world peace and unity amidst a time of unprecedented possibilities in travel and communication.

“My world seems like a science fiction world even to those of us who have lived through the recent years to reach the present,” Asimov tells the founding father. After explaining to Franklin the capabilities of space travel, satellites, and fossil fuels, Asimov also lets him in on the difficult prospects of nuclear war, gas shortages, and pollution. As in much of Asimov’s work, the tragic irony of looming catastrophe in an age of rapid advancement is all too real:

Franklin said, “You say, the, that every nation needs every other nation; for oil, or for metal, or for industrial experience and technological knowledge. You say that the oil supplies will soon be used up and that permanent new energy supplies must be found by nations working together. You say that failure to cooperate means the end of your technological civilization and the death of billions You say it all as though it were such apparent truth that it wearied you to have to explain it to me.”

In the final installment, Franklin gives his simple advice to Asimov on the message great writers must strive to express to avoid the end of civilization: “Unite or die.”

Asimov criticized American anti-intellectualism and widespread ignorance, but it is difficult to say exactly what the science fiction writer might think of the state of his country if he could see it on his 100th birthday. He would be quite surprised (or not at all) at the ubiquity of touchscreen technology and the prospects of artificial intelligence. Perhaps he would be disappointed in the failure of 21st-century people to unite in solving our climate crisis. But one thing is for sure: if Asimov could visit the United States today, he would be appalled to find that we are still stubbornly holding out on a shift to the metric system.

Featured image by Lucian Lupinski in The Saturday Evening Post, May 1974

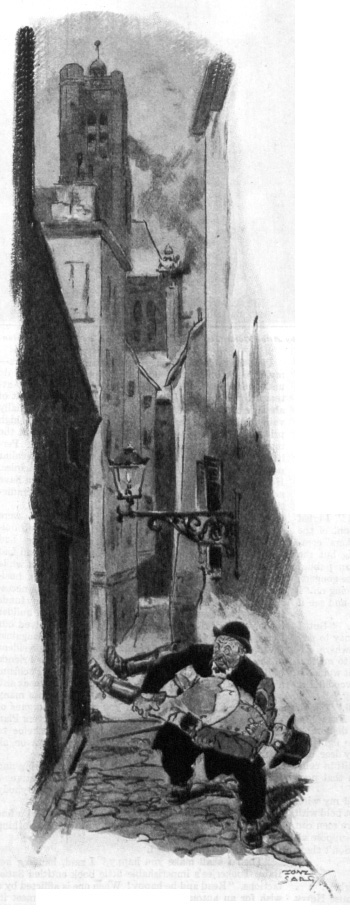

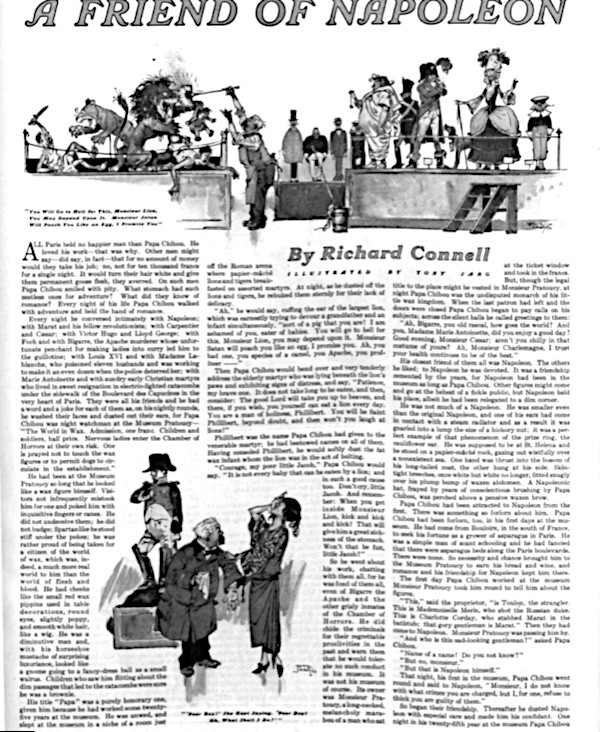

“A Friend of Napoleon” by Richard Connell

Author of the widely-read short story “The Most Dangerous Game,” Richard Connell wrote fiction, screenplays, and more in the early 20th century. His O. Henry Prize story “A Friend of Napoleon” follows a well-meaning wax museum night guard in a farcical romp of crime and romance.

Published on June 30, 1923

All Paris held no happier man than Papa Chibou. He loved his work — that was why. Other men might say — did say, in fact — that for no amount of money would they take his job; no, not for ten thousand francs for a single night. It would turn their hair white and give them permanent goose flesh, they averred. On such men Papa Chibou smiled with pity. What stomach had such zestless ones for adventure? What did they know of romance? Every night of his life Papa Chibou walked with adventure and held the hand of romance.

Every night he conversed intimately with Napoleon; with Marat and his fellow revolutionists; with Carpentier and Caesar; with Victor Hugo and Lloyd George; with Foch and with Bigarre, the Apache murderer whose unfortunate penchant for making ladies into curry led him to the guillotine; with Louis XVI and with Madame Lablanche, who poisoned eleven husbands and was working to make it an even dozen when the police deterred her; with Marie Antoinette and with sundry early Christian martyrs who lived in sweet resignation in electric-lighted catacombs under the sidewalk of the Boulevard des Capucines in the very heart of Paris. They were all his friends and he had a word and a joke for each of them as, on his nightly rounds, he washed their faces and dusted out their ears, for Papa Chibou was night watchman at the Museum Pratoucy — “The World in Wax. Admission, one franc. Children and soldiers, half price. Nervous ladies enter the Chamber of Horrors at their own risk. One is prayed not to touch the wax figures or to permit dogs to circulate in the establishment.”

He had been at the Museum Pratoucy so long that he looked like a wax figure himself. Visitors not infrequently mistook h im for one and poked him with inquisitive fingers or canes. He did not undeceive them; he did not budge; Spartan-like he stood stiff under the pokes; he was rather proud of being taken for a citizen of the world of wax, which was, indeed, a much more real world to him than the world of flesh and blood. He had cheeks like the small red wax pippins used in table decorations, round eyes, slightly poppy, and smooth white hair, like a wig. He was a diminutive man and, with his horseshoe mustache of surprising luxuriance, looked like a gnome going to a fancy-dress ball as a small walrus. Children who saw him flitting about the dim passages that led to the catacombs were sure he was a brownie.

His title “Papa” was a purely honorary one, given him because he had worked some twenty-five years at the museum. He was unwed, and slept at the museum in a niche of a room just off the Roman arena where papier-mâché lions and tigers breakfasted on assorted martyrs. At night, as he dusted off the lions and tigers, he rebuked them sternly for their lack of delicacy.

“Ah,” he would say, cuffing the ear of the largest lion, which was earnestly trying to devour a grandfather and an infant simultaneously, “sort of a pig that you are! I am ashamed of you, eater of babies. You will go to hell for this, Monsieur Lion, you may depend upon it. Monsieur Satan will poach you like an egg, I promise you. Ah, you bad one, you species of a camel, you Apache, you profiteer —”

Then Papa Chibou would bend over and very tenderly address the elderly martyr who was lying beneath the lion’s paws and exhibiting signs of distress, and say, “Patience, my brave one. It does not take long to be eaten, and then, consider: The good Lord will take you up to heaven, and there, if you wish, you yourself can eat a lion every day. You are a man of holiness, Phillibert. You will be Saint Phillibert, beyond doubt, and then won’t you laugh at lions!”

Phillibert was the name Papa Chibou had given to the venerable martyr; he had bestowed names on all of them. Having consoled Phillibert, he would softly dust the fat wax infant whom the lion was in the act of bolting.

“Courage, my poor little Jacob,” Papa Chibou would say. “It is not every baby that can be eaten by a lion; and in such a good cause too. Don’t cry, little Jacob. And remember: When you get inside Monsieur Lion, kick and kick and kick! That will give him a great sickness of the stomach. Won’t that be fun, little Jacob?”

So he went about his work, chatting with them all, for he was fond of them all, even of Bigarre the Apache and the other grisly inmates of the Chamber of Horrors. He did chide the criminals for their regrettable proclivities in the past and warn them that he would tolerate no such conduct in his museum. It was not his museum of course. Its owner was Monsieur Pratoucy, a long-necked, melancholy marabou of a man who sat at the ticket window and took in the francs. But, though the legal title to the place might be vested in Monsieur Pratoucy, at night Papa Chibou was the undisputed monarch of his little wax kingdom. When the last patron had left and the doors were closed Papa Chibou began to pay calls on his subjects; across the silent halls he called greetings to them:

“Ah, Bigarre, you old rascal, how goes the world? And you, Madame Marie Antoinette, did you enjoy a good day? Good evening, Monsieur Caesar; aren’t you chilly in that costume of yours? Ah, Monsieur Charlemagne, I trust your health continues to be of the best.”

His closest friend of them all was Napoleon. The others he liked; to Napoleon he was devoted. It was a friendship cemented by the years, for Napoleon had been in the museum as long as Papa Chibou. Other figures might come and go at the behest of a fickle public, but Napoleon held his place, albeit he had been relegated to a dim corner.

He was not much of a Napoleon. He was smaller even than the original Napoleon, and one of his ears had come in contact with a steam radiator and as a result it was gnarled into a lump the size of a hickory nut; it was a perfect example of that phenomenon of the prize ring, the cauliflower ear. He was supposed to be at St. Helena and he stood on a papier-mâché rock, gazing out wistfully over a nonexistent sea. One hand was thrust into the bosom of his long-tailed coat, the other hung at his side. Skintight breeches, once white but white no longer, fitted snugly over his plump bump of waxen abdomen. A Napoleonic hat, frayed by years of conscientious brushing by Papa Chibou, was perched above a pensive waxen brow.

Papa Chibou had been attracted to Napoleon from the first. There was something so forlorn about him. Papa Chibou had been forlorn, too, in his first days at the museum. He had come from Bouloire, in the south of France, to seek his fortune as a grower of asparagus in Paris. He was a simple man of scant schooling and he had fancied that there were asparagus beds along the Paris boulevards. There were none. So necessity and chance brought him to the Museum Pratoucy to earn his bread and wine, and romance and his friendship for Napoleon kept him there.

The first day Papa Chibou worked at the museum Monsieur Pratoucy took him round to tell him about the figures.

“This,” said the proprietor, “is Toulon, the strangler. This is Mademoiselle Merle, who shot the Russian duke. This is Charlotte Corday, who stabbed Marat in the bathtub; that gory gentleman is Marat.” Then they had come to Napoleon. Monsieur Pratoucy was passing him by.

“And who is this sad-looking gentleman?” asked Papa Chibou.

“Name of a name! Do you not know?”

“But no, monsieur.”

“But that is Napoleon himself.”

That night, his first in the museum, Papa Chibou went round and said to Napoleon, “Monsieur, I do not know with what crimes you are charged, but I, for one, refuse to think you are guilty of them.”

So began their friendship. Thereafter he dusted Napoleon with especial care and made him his confidant. One night in his twenty-fifth year at the museum Papa Chibou said to Napoleon, “You observed those two lovers who were in here tonight, did you not, my good Napoleon? They thought it was too dark in this corner for us to see, didn’t they? But we saw him take her hand and whisper to her. Did she blush? You were near enough to see. She is pretty, isn’t she, with her bright dark eyes? She is not a French girl; she is an American; one can tell that by the way she doesn’t roll her r’s. The young man, he is French; and a fine young fellow he is, or I’m no judge. He is so slender and erect, and he has courage, for he wears the war cross; you noticed that, didn’t you? He is very much in love, that is sure. This is not the first time I have seen them. They have met here before, and they are wise, for is this not a spot most romantic for the meetings of lovers?”

Papa Chibou flicked a speck of dust from Napoleon’s good ear.

“Ah,” he exclaimed, “it must be a thing most delicious to be young and in love! Were you ever in love, Napoleon? No? Ah, what a pity! I know, for I, too, have had no luck in love. Ladies prefer the big, strong men, don’t they? Well, we must help these two young people, Napoleon. We must see that they have the joy we missed. So do not let them know you are watching them if they come here tomorrow night. I will pretend I do not see.”

Each night after the museum had closed, Papa Chibou gossiped with Napoleon about the progress of the love affair between the American girl with the bright dark eyes and the slender, erect young Frenchman.

“All is not going well,” Papa Chibou reported one night, shaking his head. “There are obstacles to their happiness.

“He has little money, for he is just beginning his career. I heard him tell her so tonight. And she has an aunt who has other plans for her. What a pity if fate should part them! But you know how unfair fate can be, don’t you, Napoleon? If we only had some money we might be able to help him, but I, myself, have no money, and I suppose you, too, were poor, since you look so sad. But attend; tomorrow is a day most important for them. He has asked her if she will marry him, and she has said that she will tell him tomorrow night at nine in this very place. I heard them arrange it all. If she does not come it will mean no. I think we shall see two very happy ones here tomorrow night, eh, Napoleon?”

The next night when the last patron had gone and Papa Chibou had locked the outer door, he came to Napoleon, and tears were in his eyes.

“You saw, my friend?” broke out Papa Chibou. “You observed? You saw his face and how pale it grew? You saw his eyes and how they held a thousand agonies? He waited until I had to tell him three times that the museum was closing. I felt like an executioner, I assure you; and he looked up at me as only a man condemned can look. He went out with heavy feet; he was no longer erect. For she did not come, Napoleon; that girl with the bright dark eyes did not come. Our little comedy of love has become a tragedy, monsieur. She has refused him, that poor, that unhappy young man.”

On the following night at closing time Papa Chibou came hurrying to Napoleon; he was a-quiver with excitement.

“She was here!” he cried. “Did you see her? She was here and she kept watching and watching; but, of course, he did not come. I could tell from his stricken face last night that he had no hope. At last I dared to speak to her. I said to her, ‘Mademoiselle, a thousand pardons for the very great liberty I am taking, but it is my duty to tell you — he was here last night and he waited till closing time. He was all of a paleness, mademoiselle, and he chewed his fingers in his despair. He loves you, mademoiselle; a cow could see that. He is devoted to you; and he is a fine young fellow, you can take an old man’s word for it. Do not break his heart, mademoiselle.’ She grasped my sleeve. ‘You know him, then?’ she asked. ‘You know where I can find him?’ ‘Alas, no,’ I said. ‘I have only seen him here with you.’ ‘Poor boy!’ she kept saying. ‘Poor boy! Oh, what shall I do? I am in dire trouble. I love him, monsieur.’ ‘But you did not come,’ I said. ‘I could not.’ she replied, and she was weeping. ‘I live with an aunt; a rich tiger she is, monsieur, and she wants me to marry a count, a fat leering fellow who smells of attar of roses and garlic. My aunt locked me in my room. And now I have lost the one I love, for he will think I have refused him, and he is so proud he will never ask me again.’ ‘But surely you could let him know?’ I suggested. ‘But I do not know where he lives,’ she said. ‘And in a few days my aunt is taking me off to Rome, where the count is, and oh, dear, oh, dear, oh, dear — ’ And she wept on my shoulder, Napoleon, that poor little American girl with the bright dark eyes.”

Papa Chibou began to brush the Napoleonic hat.

“I tried to comfort her,” he said. “I told her that the young man would surely find her, that he would come back and haunt the spot where they had been happy, but I was telling her what I did not believe. ‘He may come tonight,’ I said, ‘or tomorrow.’ She waited until it was time to close the museum. You saw her face as she left; did it not touch you in the heart?”

Papa Chibou was downcast when he approached Napoleon the next night.

“She waited again till closing time,” he said, “but he did not come. It made me suffer to see her as the hours went by and her hope ebbed away. At last she had to leave, and at the door she said to me, ‘If you see him here again, please give him this.’ She handed me this card, Napoleon. See, it says, ‘I am at the Villa Rosina, Rome. I love you. Nina.’ Ah, the poor, poor young man. We must keep a sharp watch for him, you and I.”

Papa Chibou and Napoleon did watch at the Museum Pratoucy night after night. One, two, three, four, five nights they watched for him. A week, a month, more months passed, and he did not come. There came instead one day news of so terrible a nature that it left Papa Chibou ill and trembling. The Museum Pratoucy was going to have to close its doors.

“It is no use,” said Monsieur Pratoucy, when he dealt this blow to Papa Chibou. “I cannot go on. Already I owe much, and my creditors are clamoring. People will no longer pay a franc to see a few old dummies when they can see an army of red Indians, Arabs, brigands and dukes in the moving pictures. Monday the Museum Pratoucy closes its doors forever.”

“But, Monsieur Pratoucy,” exclaimed Papa Chibou, aghast, “what about the people here? What will become of Marie Antoinette, and the martyrs and Napoleon?”

“Oh,” said the proprietor, “I’ll be able to realize a little on them perhaps. On Tuesday they will be sold at auction. Someone may buy them to melt up.”

“To melt up, monsieur?” Papa Chibou faltered.

“But certainly. What else are they good for?”

“But surely monsieur will want to keep them; a few of them anyhow?”

“Keep them? Aunt of the devil, but that is a droll idea! Why should anyone want to keep shabby old wax dummies?”

“I thought,” murmured Papa Chibou, “that you might keep just one — Napoleon, for example — as a remembrance — ”

“Uncle of Satan, but you have odd notions! To keep a souvenir of one’s bankruptcy!”

Papa Chibou went away to his little hole in the wall. He sat on his cot and fingered his mustache for an hour; the news had left him dizzy, had made a cold vacuum under his belt buckle. From under his cot, at last, he took a wooden box, unlocked three separate locks and extracted a sock. From the sock he took his fortune, his hoard of big copper ten-centime pieces, tips he had saved for years. He counted them over five times most carefully; but no matter how he counted them he could not make the total come to more than two hundred and twenty-one francs.

That night he did not tell Napoleon the news. He did not tell any of them. Indeed he acted even more cheerful than usual as he went from one figure to another. He complimented Madame Lablanche, the lady of the poisoned spouses, on how well she was looking. He even had a kindly word to say to the lion that was eating the two martyrs.

“After all, Monsieur Lion,” he said, “I suppose it is as proper for you to eat martyrs as it is for me to eat bananas. Probably bananas do not enjoy being eaten any more than martyrs do. In the past I have said harsh things to you, Monsieur Lion; I am sorry I said them, now. After all, it is hardly your fault that you eat people. You were born with an appetite for martyrs, just as I was born poor.” And he gently tweaked the lion’s papier-mâché ear.

When he came to Napoleon, Papa Chibou brushed him with unusual care and thoroughness. With a moistened cloth he polished the imperial nose, and he took pains to be gentle with the cauliflower ear. He told Napoleon the latest joke he had heard at the cabmen’s café where he ate his breakfast of onion soup, and, as the joke was mildly improper, nudged Napoleon in the ribs, and winked at him.

“We are men of the world, eh, old friend?” said Papa Chibou. “We are philosophers, is that not so?” Then he added, “We take what life sends us, and sometimes it sends hardnesses.”

He wanted to talk more with Napoleon, but somehow he couldn’t; abruptly, in the midst of a joke, Papa Chibou broke off and hurried down into the depths of the Chamber of Horrors and stood there for a very long time staring at an unfortunate native of Siam being trodden on by an elephant.

It was not until the morning of the auction sale that Papa Chibou told Napoleon. Then, while the crowd was gathering, he slipped up to Napoleon in his corner and laid his hand on Napoleon’s arm.

“One of the hardnesses of life has come to us, old friend,” he said. “They are going to try to take you away. But, courage! Papa Chibou does not desert his friends. Listen!” And Papa Chibou patted his pocket, which gave forth a jingling sound.

The bidding began. Close to the auctioneer’s desk stood a man, a wizened, rodent-eyed man with a diamond ring and dirty fingers. Papa Chibou’s heart went down like an express elevator when he saw him, for he knew that the rodent-eyed man was Mogen, the junk king of Paris. The auctioneer, in a voice slightly encumbered by adenoids, began to sell the various items in a hurried, perfunctory manner.

“Item 3 is Julius Caesar, toga and sandals thrown in. How much am I offered? One hundred and fifty francs? Dirt cheap for a Roman emperor, that is. Who’ll make it two hundred? Thank you, Monsieur Mogen. The noblest Roman of them all is going at two hundred francs. Are you all through at two hundred? Going, going, gone! Julius Caesar is sold to Monsieur Mogen.”

Papa Chibou patted Caesar’s back sympathetically.

“You are worth more, my good Julius,” he said in a whisper. “Good-by.”

He was encouraged. If a comparatively new Caesar brought only two hundred, surely an old Napoleon would bring no more.

The sale progressed rapidly. Monsieur Mogen bought the entire Chamber of Horrors. He bought Marie Antoinette, and the martyrs and lions. Papa Chibou, standing near Napoleon, withstood the strain of waiting by chewing his mustache.

The sale was very nearly over and Monsieur Mogen had bought every item, when, with a yawn, the auctioneer droned: “Now, ladies and gentlemen, we come to Item 573, a collection of odds and ends, mostly damaged goods, to be sold in one lot. The lot includes one stuffed owl that seems to have molted a bit; one Spanish shawl, torn; the head of an Apache who has been guillotined, body missing; a small wax camel, no humps; and an old wax figure of Napoleon, with one ear damaged. What am I offered for the lot?”

Papa Chibou’s heart stood still. He laid a reassuring hand on Napoleon’s shoulder. “The fool,” he whispered in Napoleon’s good ear, “to put you in the same class as a camel, no humps, and an owl. But never mind. It is lucky for us, perhaps.”

“How much for this assortment?” asked the auctioneer.

“One hundred francs,” said Mogen, the junk king.

“One hundred and fifty,” said Papa Chibou, trying to be calm. He had never spent so vast a sum all at once in his life.

Mogen fingered the material in Napoleon’s coat.

“Two hundred,” said the junk king.

“Are you all through at two hundred?” queried the auctioneer.

“Two hundred and twenty-one,” called Papa Chibou. His voice was a husky squeak.

Mogen from his rodent eyes glared at Papa Chibou with annoyance and contempt. He raised his dirtiest finger — the one with the diamond ring on it — toward the auctioneer.

“Monsieur Mogen bids two hundred and twenty-five,” droned the auctioneer. “Do I hear two hundred and fifty?”

Papa Chibou hated the world. The auctioneer cast a look his direction.

“Two hundred and twenty-five is bid,” he repeated. “Are you all through at two hundred and twenty-five? Going, going — sold to Monsieur Mogen for two hundred and twenty-five francs.”

Stunned, Papa Chibou heard Mogen say casually, “I’ll send round my carts for this stuff in the morning.”

This stuff!

Dully and with an aching breast Papa Chibou went to his room down by the Roman arena. He packed his few clothes into a box. Last of all he slowly took from his cap the brass badge he had worn for so many years; it bore the words “Chief Watchman.” He had been proud of that title, even if it was slightly inaccurate; he had been not only the chief but the only watchman. Now he was nothing. It was hours before he summoned up the energy to take his box round to the room he had rented high up under the roof of a tenement in a nearby alley. He knew he should start to look for another job at once, but he could not force himself to do so that day. Instead, he stole back to the deserted museum and sat down on a bench by the side of Napoleon. Silently he sat there all night; but he did not sleep; he was thinking, and the thought that kept pecking at his brain was to him a shocking one. At last, as day began to edge its pale way through the dusty windows of the museum, Papa Chibou stood up with the air of a man who has been through a mental struggle and has made up his mind.

“Napoleon,” he said, “we have been friends for a quarter of a century and now we are to be separated because a stranger had four francs more than I had. That may be lawful, my old friend, but it is not justice. You and I, we are not going to be parted.”

Paris was not yet awake when Papa Chibou stole with infinite caution into the narrow street beside the museum. Along this street toward the tenement where he had taken a room crept Papa Chibou. Sometimes he had to pause for breath, for in his arms he was carrying Napoleon.

Two policemen came to arrest Papa Chibou that very afternoon. Mogen had missed Napoleon, and he was a shrewd man. There was not the slightest doubt of Papa Chibou’s guilt. There stood Napoleon in the corner of his room, gazing pensively out over the housetops. The police bundled the overwhelmed and confused Papa Chibou into the police patrol, and with him, as damning evidence, Napoleon.

In his cell in the city prison Papa Chibou sat with his spirit caved in. To him jails and judges and justice were terrible and mysterious affairs. He wondered if he would be guillotined; perhaps not, since his long life had been one of blameless conduct; but the least he could expect, he reasoned, was a long sentence to hard labor on Devil’s Island, and guillotining had certain advantages over that. Perhaps it would be better to be guillotined, he told himself, now that Napoleon was sure to be melted up.

The keeper who brought him his meal of stew was a pessimist of jocular tendencies.

“A pretty pickle,” said the keeper; “and at your age too. You must be a very wicked old man to go about stealing dummies. What will be safe now? One may expect to find the Eiffel Tower missing any morning. Dummy stealing! What a career! We have had a man in here who stole a trolley car, and one who made off with the anchor of a steamship, and even one who pilfered a hippopotamus from a zoo, but never one who stole a dummy — and an old one-eared dummy, at that! It is an affair extraordinary!”

“And what did they do to the gentleman who stole the hippopotamus?” inquired Papa Chibou tremulously.

The keeper scratched his head to indicate thought.

“I think,” he said, “that they boiled him alive. Either that or they transported him for life to Morocco; I don’t recall exactly.”

Papa Chibou’s brow grew damp.

“It was a trial most comical, I can assure you,” went on the keeper. “The judges were Messieurs Bertouf, Goblin and Perouse — very amusing fellows, all three of them. They had fun with the prisoner; how I laughed. Judge Bertouf said, in sentencing him, ‘We must be severe with you, pilferer of hippopotamuses. We must make of you an example. This business of hippopotamus pilfering is getting all too common in Paris.’ They are witty fellows, those judges.”

Papa Chibou grew a shade paler.

“The Terrible Trio?” he asked.

“The Terrible Trio,” replied the keeper cheerfully.

“Will they be my judges?” asked Papa Chibou.

“Most assuredly,” promised the keeper, and strolled away humming happily and rattling his big keys.

Papa Chibou knew then that there was no hope for him. Even into the Museum Pratoucy the reputation of those three judges had penetrated, and it was a sinister reputation indeed. They were three ancient, grim men who had fairly earned their title, The Terrible Trio, by the severity of their sentences; evildoers blanched at their names, and this was a matter of pride to them.

Shortly the keeper came back; he was grinning.

“You have the devil’s own luck, old-timer,” he said to Papa Chibou. “First you have to be tried by The Terrible Trio, and then you get assigned to you as lawyer none other than Monsieur Georges Dufayel.”

“And this Monsieur Dufayel, is he then not a good lawyer?” questioned Papa Chibou miserably.

The keeper snickered.

“He has not won a case for months,” he answered, as if it were the most amusing thing imaginable. “It is really better than a circus to hear him muddling up his clients’ affairs in court. His mind is not on the case at all. Heaven knows where it is. When he rises to plead before the judges he has no fire, no passion. He mumbles and stutters. It is a saying about the courts that one is as good as convicted who has the ill luck to draw Monsieur Georges Dufayel as his advocate. Still, if one is too poor to pay for a lawyer, one must take what he can get. That’s philosophy, eh, old-timer?”

Papa Chibou groaned.

“Oh, wait till tomorrow,” said the keeper gayly. “Then you’ll have a real reason to groan.”

“But surely I can see this Monsieur Dufayel.”

“Oh, what’s the use? You stole the dummy, didn’t you? It will be there in court to appear against you. How entertaining! Witness for the prosecution: Monsieur Napoleon. You are plainly as guilty as Cain, old-timer, and the judges will boil your cabbage for you very quickly and neatly, I can promise you that. Well, see you tomorrow. Sleep well.”

Papa Chibou did not sleep well. He did not sleep at all, in fact, and when they marched him into the inclosure where sat the other nondescript offenders against the law he was shaken and utterly wretched. He was overawed by the great court room and the thick atmosphere of seriousness that hung over it.

He did pluck up enough courage to ask a guard, “Where is my lawyer, Monsieur Dufayel?”

“Oh, he’s late, as usual,” replied the guard. And then, for he was a waggish fellow, he added, “If you’re lucky he won’t come at all.”

Papa Chibou sank down on the prisoners’ bench and raised his eyes to the tribunal opposite. His very marrow was chilled by the sight of The Terrible Trio. The chief judge, Bertouf, was a vast puff of a man, who swelled out of his judicial chair like a poisonous fungus. His black robe was familiar with spilled brandy, and his dirty judicial bib was askew. His face was bibulous and brutal, and he had the wattles of a turkey gobbler. Judge Goblin, on his right, looked to have mummified; he was at least a hundred years old and had wrinkled parchment skin and red-rimmed eyes that glittered like the eyes of a cobra. Judge Perouse was one vast jungle of tangled grizzled whisker, from the midst of which projected a cockatoo’s beak of a nose; he looked at Papa Chibou and licked his lips with a long pink tongue. Papa Chibou all but fainted; he felt no bigger than a pea, and less important; as for his judges, they seemed enormous monsters.

The first case was called, a young swaggering fellow who had stolen an orange from a pushcart.

“Ah, Monsieur Thief,” rumbled Judge Bertouf with a scowl, “you are jaunty now. Will you be so jaunty a year from today when you are released from prison? I rather think not. Next case.”

Papa Chibou’s heart pumped with difficulty. A year for an orange — and he had stolen a man! His eyes roved round the room and he saw two guards carrying in something which they stood before the judges. It was Napoleon.

A guard tapped Papa Chibou on the shoulder. “You’re next,” he said.

“But my lawyer, Monsieur Dufayel — ” began Papa Chibou.

“You’re in hard luck,” said the guard, “for here he comes.”

Papa Chibou in a daze found himself in the prisoner’s dock. He saw coming toward him a pale young man. Papa Chibou recognized him at once. It was the slender, erect young man of the museum. He was not very erect now; he was listless. He did not recognize Papa Chibou; he barely glanced at him.

“You stole something,” said the young lawyer, and his voice was toneless. “The stolen goods were found in your room. I think we might better plead guilty and get it over with.”

“Yes, monsieur,” said Papa Chibou, for he had let go all his hold on hope. “But attend a moment. I have something — a message for you.”

Papa Chibou fumbled through his pockets and at last found the card of the American girl with the bright dark eyes. He handed it to Georges Dufayel.

“She left it with me to give to you,” said Papa Chibou. “I was chief watchman at the Museum Pratoucy, you know. She came there night after night, to wait for you.”

The young man gripped the sides of the card with both hands; his face, his eyes, everything about him seemed suddenly charged with new life.

“Ten thousand million devils!” he cried. “And I doubted her! I owe you much, monsieur. I owe you everything.” He wrung Papa Chibou’s hand.

Judge Bertouf gave an impatient judicial grunt.

“We are ready to hear your case, Advocate Dufavel,” said the judge, “if you have one.”

The court attendants sniggered.

“A little moment, monsieur the judge,” said the lawyer. He turned to Papa Chibou. “Quick,” he shot out, “tell me about the crime you are charged with. What did you steal?”

“Him,” replied Papa Chibou, pointing.

“That dummy of Napoleon?”

Papa Chibou nodded.

“But why?”

Papa Chibou shrugged his shoulders.

“Monsieur could not understand.”

“But you must tell me!” said the lawyer urgently. “I must make a plea for you. These savages will be severe enough, in any event; but I may be able to do something. Quick; why did you steal this Napoleon?”

“I was his friend,” said Papa Chibou. “The museum failed. They were going to sell Napoleon for junk, Monsieur Dufayel. He was my friend. I could not desert him.”

The eyes of the young advocate had caught fire; they were lit with a flash. He brought his fist down on the table.

“Enough!” he cried.

Then he rose in his place and addressed the court. His voice was low, vibrant and passionate; the judges, in spite of themselves, leaned forward to listen to him.

“May it please the honorable judges of this court of France,” he began, “my client is guilty. Yes, I repeat in a voice of thunder, for all France to hear, for the enemies of France to hear, for the whole wide world to hear, he is guilty. He did steal this figure of Napoleon, the lawful property of another. I do not deny it. This old man, Jerome Chibou, is guilty, and I for one am proud of his guilt.”

Judge Bertouf grunted.

“If your client is guilty, Advocate Dufayel,” he said, “that settles it. Despite your pride in his guilt, which is a peculiar notion, I confess, I am going to sentence him to — ”

“But wait, your honor!” Dufayel’s voice was compelling. “You must, you shall hear me! Before you pass sentence on this old man, let me ask you a question.”

“Well?”

“Are you a Frenchman, Judge Bertouf?”

“But certainly.”

“And you love France?”

“Monsieur has not the effrontery to suggest otherwise?”

“No. I was sure of it. That is why you will listen to me.”

“I listen.”

“I repeat then: Jerome Chibou is guilty. In the law’s eyes he is a criminal. But in the eyes of France and those who love her his guilt is a glorious guilt; his guilt is more honorable than innocence itself.”

The three judges looked at one another blankly; Papa Chibou regarded his lawyer with wide eyes; George Dufayel spoke on.