Tiger Woods and More Triumphant Sports Returns

As Tiger Woods steps onto the grass at The Masters this week, the eyes of the sports world are upon him. Woods, returning from what many had thought was a career-ending accident, has defied the odds before. In 2019, Woods won The Masters after an 11-year drought at major tournaments. Could Woods make another thrilling return? In that spirit, here are five other returns by athletes that should never have been counted out.

Before we look at the Big Five, here’s a Bonus Two-for-One Special:

Bonus: Magic Johnson and Larry Bird

The Best of the Dream Team (Uploaded to YouTube by Olympics)

In 1992, Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics was on the verge of retirement. Plagued by back problems, he’d had a disc removed, missed 37 games during that season, and was headed out the door. His great friend and nemesis, Magic Johnson of the L.A. Lakers, had retired in 1991 after being diagnosed as HIV-positive. However, the two had a chance for one last run together: the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. Joining one of the greatest athletic teams ever assembled, Bird, Magic, and the rest of Team USA stormed their way to a gold medal. For basketball fans that had watched the pair battle from the 1979 NCAA Finals and through the entire 1980s in the NBA, well, that’s why they called it “The Dream Team.” While Bird did retire after the Olympics, Magic returned to the NBA as a player in 1996, helping the team get fourth seed in the playoffs. After the Lakers lost to the Rockets, Magic retired for good.

5. George Foreman

George Foreman in 1973 (Photo by Bert Verhoeff via Wikimedia Commons; Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication)

One of the best to ever lace up a pair of boxing gloves, George Foreman took gold in the 1968 Olympics as a heavyweight. Foreman went on to knock out an undefeated Joe Frazier to become heavyweight champ in 1973. His title reign came to an end at the hands of Muhammad Ali at 1974’s legendary “Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman retired in 1977. After spending several years as a minister, Foreman came back to boxing in 1987. In 1994, the 45-year-old Foreman knocked out Michael Moorer to become the unified heavyweight champion. He remains the oldest man to be heavyweight champion.

4. Bethany Hamilton

This Iz My Story (Uploaded to YouTube by Bethany Hamilton)

Bethany Hamilton excelled at surfing from an early age. An avid competitor by age eight with sponsorships by age ten, Hamilton had her eyes on big titles. However, in 2003 when she was 13, the unthinkable happened. During a surfing excursion, a 14-foot long tiger shark bit off Hamilton’s left arm below her shoulder. It was a trauma that would have crushed most people, but not Hamilton. She returned to the waves a mere month after the incident. In 2005, she took first in the NSSA Nationals and won her first pro tournament in 2007.

3. Mario Lemieux

Lemieux Scored 100 Points 10 Different Times (Uploaded to YouTube by NHL)

There’s no debate about the greatness of Mario Lemieux. He’s widely regarded as one of the greatest hockey players ever. Lemieux debuted for the Pittsburgh Penguins in 1984 and quickly became a star. He was Rookie of the Year and was only outscored in his sophomore season by Wayne Gretzky. Though Lemieux would struggle with back injuries, he was a major force in the NHL as one of the sport’s biggest scorers. In 1993, “Super Mario” was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma. Undeterred, he continued to play, even on the same day as radiation treatments. Incredibly, he won the scoring title that year. Though he continued to play at a high level, the years of back problems and his earlier battle with cancer factored in to Lemieux’s decision to retire in 1997. With the Penguins facing money trouble, Lemieux came in with a plan to become the team’s majority owner. He helped turn things around the ledger, and then did something more incredible: he returned to the ice. Lemieux played from 2000 to 2006, ending his career with dozens of records and an Olympic gold medal from 2002.

2. Michael Jordan

The Best of Jordan’s Playoff Games (Uploaded to YouTube by NBA)

For Michael Jordan, an NBA championship wasn’t a question of “if,” but a question of “when.” Joining the league in decade dominated by the Celtics and the Lakers, Jordan turned around the fortunes of the Chicago Bulls. He led the team to a finals win in 1991, and then again in 1992 and 1993. Tragically, Jordan’s father, James Jordan, Sr., was murdered by carjackers in July of 1993. That October, Jordan retired, citing his father’s death, a loss of desire to play, and general exhaustion. After detour to play minor league baseball, Jordan issued a two-word press release (“I’m back”) and returned to the NBA in March 1995. He lifted the struggling Bulls into the playoffs, where they lost to the Orlando Magic. As the meme goes, Jordan took that personally. Over the next three seasons, Jordan led the Bulls to championships in 1996, 1997, and 1998, cementing his status as one of, if not the, greatest to ever play the game.

1. Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali – The Greatest of All Time (Uploaded to YouTube by Nonstop Sports)

How could The Greatest now be #1? Muhammad Ali’s life was defined by battle. Whether it was taking the Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960 or taking his draft evasion conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, Ali never backed down from a challenge. After becoming champion in 1964, Ali voiced his opposition to the war in Vietnam and proclaimed his status as a conscientious objector. His titles were stripped, and Ali fought the decisions in court. The conviction was overturned in 1971 and Ali found himself in the position to challenge Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title. Both men were undefeated going in, but it was Ali that left with his first professional loss. Of course, that didn’t mean that Ali was done. He faced Frazier again in 1974, defeating his old rival to get a shot at the then-current champ, George Foreman. At the “Rumble in the Jungle,” Ali knocked out Foreman to retake the title. He would eventually retire in 1981, a three-time heavyweight champion

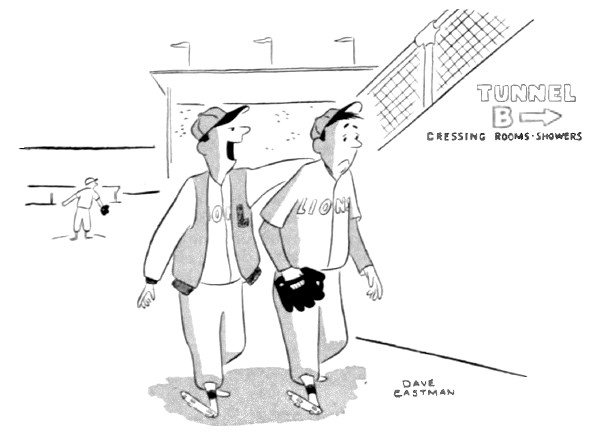

Baseball: Our One Perfect Institution

In 1908, the game was untarnished by cheating scandals and drug abuse. The top ballfield heroes were Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner, and the new song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” became a hit. With the World Series just ended, the editors looked back on the past season with satisfaction and pride in the national pastime.

In an imperfect and fretful world, we have one institution which is practically above reproach and beyond criticism. There is no movement afoot to uplift it, like the stage, or to abolish it, like marriage. No one complains that it is vulgar, like the newspapers, or that it assassinates genius, like the magazines. It rouses no class passions, and, while it has magnates, they go unhung with our approval.

This one comparatively perfect flower of our sadly defective civilization is, of course, baseball — the only important institution that the United States regards with a practically universal, uncritical, unadulterated affection. The fact doesn’t fit any theory, for baseball is somewhat of a trust and monopoly and is operated with an eye to the gate receipts.

The strength of baseball is simply that it gets results. Politics bores, the newspaper irritates, the drama frequently, at best, leaves you in doubt as to whether you have had a pleasant evening, a cold in the head takes the perfume from the rose of matrimony. But there is no doubt, no bar, no discount upon the thrill of the double play, or the deep joy of the three-bagger.

—“Our One Perfect Institution,” Editorial, October 31, 1908

The Saturday Evening Post

October 31, 1908

Featured image: Robert Robinson / SEPS

Cartoons: Take Me Out to the Ball Game

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Bo Brown

June 28, 1952

Tom Henderson

June 21, 1952

Dave Eastman

June 12, 1954

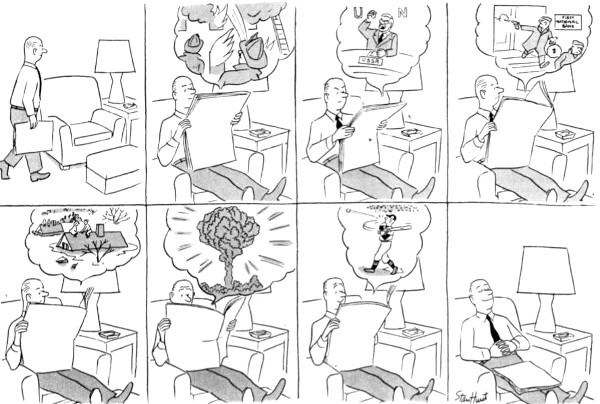

Chon Day

April 19, 1952

April 17, 1954

Bill Harrison

April 16, 1955

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

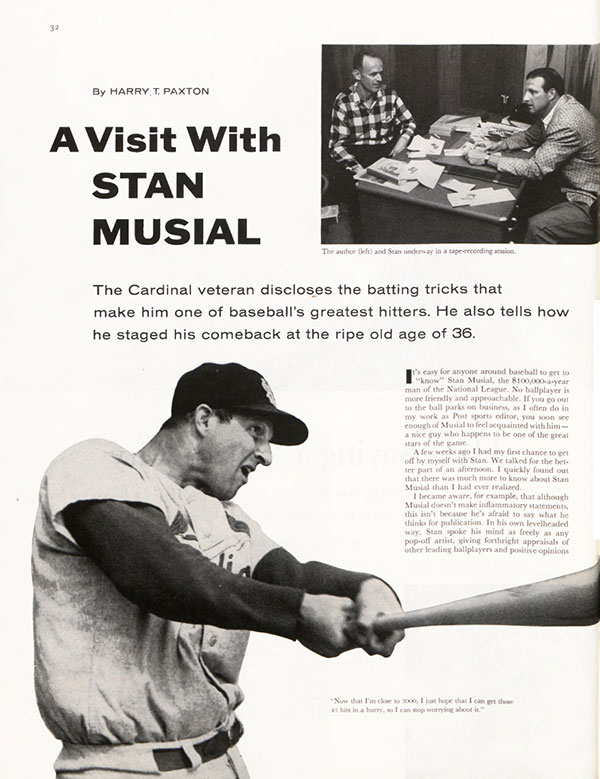

The Midwest Salutes a Hero: The Celebration of Stan Musial’s 3,000th Hit

On Tuesday afternoon May 13, 1958, in the top of the sixth inning at Chicago’s historic Wrigley Field, Stanley Frank Musial was announced as a pinch-hitter for the St. Louis Cardinals. Musial was only one hit shy of a Major League Baseball milestone, 3,000 career hits — only seven players had ever entered that exclusive club, and no one since 1942. Ideally, Musial would have loved to break into the 3000-hit club before the adoring St. Louis fans, but if anything best epitomized his career, it was that he was a team player not focused on individual plaudits. With St. Louis down 3-1 with a runner on second base, Musial stepped in as the potential tying run.

Young Cubs right-handed Moe Drabowsky — coincidentally born in Poland where Musial’s father hailed from — peered in for the sign. Musial took his unique stance in the left-handed hitter’s batter box, once described by pitcher Ted Lyons as like “a little boy peeking around the corner to see if the cops are coming.” On a 2-2 pitch from Drabowsky, Cardinals broadcaster Harry Caray delivered his characteristically ebullient call: “Line drive! Into left field! His number three thousand! A run has scored. Musial around first, on his way to second with a double. Holy cow! He came through!” On his first try at 3,000, Musial showed the true mark of a champion rising to pressure.

The moment after Musial hit 3,000, bedlam broke out on the field. Pitchers in the bullpen, where Musial had been tanning himself earlier in the game, ran out to embrace him. Cardinals manager Fred Hutchinson came running out from the dugout to hug his star.

The train ride back to St. Louis was memorable. As George Vecsey notes in his biography, Stan Musial: An American Life, winning pitcher Sam Jones, whom Musial had pinch hit for, presented him with a magnum of champagne. Harry Caray presented Musial with a gift from all the broadcasters, commemorative gold cufflinks with a 3,000 logo. The Illinois Central Railway company provided a big cake with “3,000” in Cardinal-red icing on the top. It would be the last time that the Cardinals took this route; airplane travel had become a necessity as San Francisco and Los Angeles had just entered the National League.

The train was supposed to arrive in St. Louis shortly after 11 p.m., but it was delayed because jubilant fans were pouring out at local stops along the train’s route. At the Clinton, Illinois station, about 50 Cardinal devotees clamored for their hero, shouting: “We Want Musial! We Want Musial!” He waved from the back of the train and stretched out to give autographs. The celebration grew larger when the Cardinals arrived in the Illinois state capital in Springfield. More than 100 fans started singing, “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.” Musial came out of the dining car to greet and sign for the fans on the platform.

When Musial re-entered the train, he must have thought about another Springfield in Missouri, where in 1941, playing for the Cardinals’ Class C Minor League Affiliate, he mastered the art of hitting after failing earlier in his minor league career as a pitcher. Warm memories flooded back of the good times he had enjoyed in Springfield. As recounted in delicious detail by biographer James Giglio in Musial: From Stash to Stan The Man, he remembered how he instructed the bat boy, “Give me a bat with a hit in it”; how he peppered line drives off the Coca-Cola and 7-Up signs on the right field wall; how he made acrobatic catches in right field that thrilled the fans and showed that he had learned his lessons well from gymnastics classes taken as a youth; how he had gone fishing with teammates and then headed to a local pool hall where they could follow on ticker tape the scores of major league games.

As Vecsey wrote in his book, when the Cardinals train finally pulled into St. Louis’s Union Station near midnight, more than a half-hour late because of the earlier celebrations, nearly a thousand fans greeted Musial. “I never realized that batting a little ball around could cause so much commotion,” Musial told the crowd on the platform. “I know now how Lindbergh must have felt when he returned to St. Louis.” (Thirty-two years earlier, aviator Charles Lindbergh had piloted his plane “The Spirit of St. Louis” across the Atlantic Ocean and returned home to a hero’s welcome.) Seeing many youngsters up way past their bedtime, Musial quipped, “No school tomorrow!” (Musial’s teenaged daughter Gerry told biographer Vecsey that she remembers her mother driving her to school rather late the next day.)

The celebration was not over. High-ranking team officials and a raft of the Musial family’s close friends headed to Stan and Biggie’s, the restaurant that Musial co-owned with partner Biggie Garagnani. Musial didn’t get home until 3 a.m., but he was fresh enough the next day to hit a home run on his first at-bat for his 3,001st hit. He belted two more hits in a Cardinals victory that extended a winning streak that momentarily gave them hope of pennant contention.

Later Missouri Governor James T. Blair Jr. gave him a special license plate with “3,000” on it. Tris Speaker and Paul Waner, two of the still-living members of the 3,000-hit-club, joined the occasion. (The other living members, Ty Cobb and Napoleon Lajoie, were too ill to attend, and Cap Anson, Eddie Collins, and Honus Wagner were no longer alive.)

Looking back at how the Midwest poured out to celebrate Stan Musial’s 3,000th hit, it brings to mind President Harry Truman’s whistle stop train rides ten years earlier. A native of Independence, Missouri and an underdog in the 1948 presidential race, Truman took trains all over the country, stopping in many small towns, speaking from railway platforms to excited admirers, and ultimately winning a surprise victory over Republican candidate Thomas Dewey in November.

As a native of a heavily Democratic town near Pittsburgh, Musial had been happy for Truman’s come-from-behind triumph, but during the 1950s he supported President Dwight Eisenhower. Come 1960, however, Musial enthusiastically supported John F. Kennedy, whom he had met the year before; as Vecsey recounts, Kennedy had impressed him with his youth and energy. “They tell me you’re too old to play ball, and I’m too young to be president, but maybe we’ll both fool them,” quipped Kennedy, who at 43 was only three-and-a-half years older than Musial.

Musial retired at the end of the 1963 season with awe-inspiring statistics: career batting average of .331, 475 home runs, 1,951 runs batted, 1,949 runs scored, and 3,630 hits, second at the time only to Ty Cobb and second only to Babe Ruth in total extra-base hits. “If consistency were a place, it would be lightly populated,” goes the perceptive sports adage. No greater testimony to Stan the Man’s steady performance can be found than in how his 3,630 hits were divided: 1,815 at home and 1,815 on the road. He appeared in a record-tying 24 All-Star games and still holds the record for most home runs in the Midsummer Classic.

It was disappointing that after winning three World Series in his first four full seasons, Musial and the Cardinals never returned to the Fall Classic after 1946. But it was no surprise when in 1969 he was elected on the first ballot to the National Baseball Hall of Fame garnering over 93 percent of the vote. He became a fixture at future Hall of Fame ceremonies, his beloved harmonica in his pocket and ready to be used at the drop of a hat. According to Derrick Goold at the St. Louis Post Dispatch, one year he serenaded the crowd with a serviceable version of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

Unfortunately, in recent years Musial has slipped from memory as one of the all-time greats. Playing outside the major media markets didn’t help his marketability. The departure of the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles may have also dulled his reputation. Brooklyn fans had given Musial his nickname “Stan The Man” because of how he wrecked the home team with his bat year after year.

But to those who came of age in mid-20th century America, especially in the heartland, Stan Musial remains a paragon of excellence. On the day he retired, baseball commissioner Ford Frick praised him as “baseball’s perfect warrior . . . baseball’s perfect knight.” Musial biographer James Giglio has called him “a true sportsman and a role model . . . . virtually to all.” Two statues of him grace areas near the new Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Former President Bill Clinton remembers growing up in Arkansas doing his homework while listening to Musial’s at-bats on the radio. And when President Barack Obama bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Musial in 2011, two years before his passing, he extolled him as “an icon untarnished, a beloved pillar of the community.”

Featured image: Saturday Evening Post cover detail, “Stan the Man” by John Falter, from our May 1, 1954, issue (© SEPS)

Considering History: Baseball, Chinese Americans, and the Worst and Best of America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In honor of Asian and Pacific Islander American Heritage Month, PBS is airing this week a compelling and vital new five-part documentary, Asian Americans. This examination of the longstanding, multi-faceted histories of the Asian-American community (across many different nationalities and cultures) could not come at a more important moment, as xenophobic and racist associations of COVID-19 with China have led to a dramatic spike in harassment and hate crimes targeting Asian Americans.

Such prejudice and violence are driven by equally longstanding collective narratives of Asian Americans not only as carriers of disease, but also as fundamentally outside of and foreign to “American” identity. Even a prominently progressive American figure like Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote, as part of his famous dissent to the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision, that Chinese Americans were “a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States” (contrasting that idea with his support for African-American equality under the law). In a public lecture two years later, he went even further, arguing that “this is a race utterly foreign to us and never will assimilate with us.”

In that late 19th century era of Chinese-American exclusion, such racist and xenophobic sentiments were given voice not only in governmental and legal documents, but also in violent gatherings of white supremacist protesters and agitators. Yet in one of the most prominent sites for these angry and divisive gatherings, a sandlot in California, we can also find a far more inclusive and inspiring vision.

As anti-Chinese sentiment became a dominant social and political perspective in the 1870s, one of its leading proponents was an Irish-American businessman, labor activist, and demagogue named Denis Kearney (1847-1907). Born in County Cork, Ireland, Kearney left home at the age of 11 and sailed the globe for a decade on clipper ships, working his way up from cabin boy to first mate before finally settling in the U.S. in 1868. Over the next decade, he married a fellow Irish immigrant (Mary Ann Leary), started a family, and established a successful delivery business in San Francisco, but it was his evolving labor and anti-immigration activism that would earn him national attention.

Kearney’s activism began with a focus on labor, including specific opposition to a city monopoly on hauling and broader support for workers’ rights; to that end he helped found in 1877 a new political party, the Workingmen’s Party of California. But he became especially famous for his fiery rhetoric, often delivered at an outdoor San Francisco space known as “The Sandlot.” In speeches that often lasted as long as two hours, delivered to thousands of angry workingmen, Kearney attacked opposition politicians, advocated for violence if their demands were not met, and, more and more over time, identified Chinese Americans as the community’s true adversary (leading the era’s anti-Chinese narratives to be frequently called “Kearneyism” and “Sandlotism”).

Kearney’s oratory quickly gained national prominence, and a February 1878 Sandlot speech reprinted in the Indianapolis Times exemplifies his incendiary, violent, and anti-Chinese rhetoric. “Do not believe those who call us savages, rioters, incendiaries, and outlaws. We seek our ends calmly, rationally, at the ballot box,” he argues, but he adds, “We shall arm. We shall meet fraud and falsehood with defiance, and force with force, if need be…We are men, and propose to live like men in this free land, without the contamination of slave labor, or die like men, if need be, in asserting the rights of our race, our country, and our families.” And he concludes, “California must be all American or all Chinese. We are resolved that it shall be American, and are prepared to make it so.”

Kearney ended most of his speeches with the repeated phrase “The Chinese Must Go,” which became likewise a campaign slogan for the Workingmen’s Party of California. Profoundly influenced by these social and political developments, over the next decade-and-a-half Congress would pass the Chinese Exclusion Act and follow-up laws like the Scott and Geary Acts, measures designed not just to limit future Chinese immigration but also to destroy the nation’s existing, sizeable Chinese American community. They did not succeed at doing so, but these laws and policies did drastically affect all Chinese Americans, as illustrated by the story of a baseball team and another California sandlot.

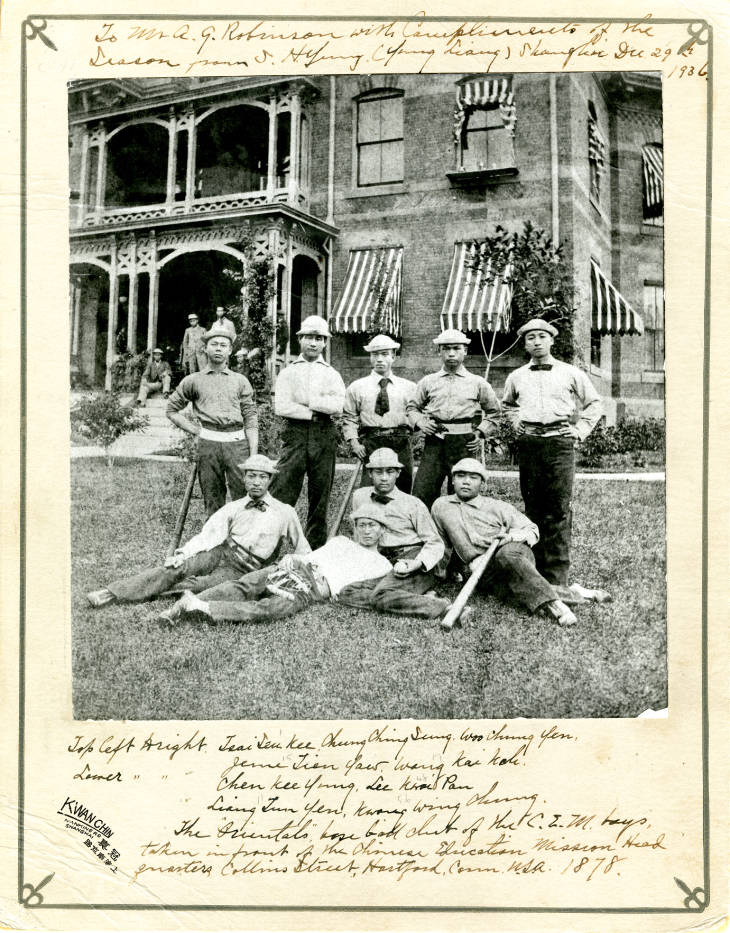

While anti-Chinese sentiment developed across the 1870s, so too did the story of a very different American community, the Hartford (CT) Chinese Educational Mission (CEM). Opened in 1872 by Yung Wing (1828-1912), the Chinese American diplomat, activist, and educator, the CEM brought 120 Chinese young men to the United States to study at New England preparatory schools and colleges, live with American families and communities, and, in Yung’s words from his 1909 autobiography My Life in China and America, “grow in knowledge and stature under New England influence.”

One product of that influence was the Chinese Educational Mission baseball team. Known officially as the Orientals but usually referred to by their preferred name, the Celestials, the team featured CEM students who had been star athletes at Yale (among other college squads). In the mid-1870s the Celestials joined one of the era’s new semi-pro baseball leagues, making quite a name for themselves on that New England regional circuit. In a chapter from his 1939 autobiography, the prominent literary scholar William Lyon Phelps, a high school and Yale classmate of many of the students, describes the team’s strengths and successes at length, noting for example of its star pitcher Wu Yangzeng, that “he was a great pitcher, impossible to hit.”

The period’s rising anti-Chinese sentiment led the U.S. government to break promises to support the Chinese Educational Mission, and in 1881 the school was closed and most of the students forced to leave the U.S. But before they disbanded, the Celestials experienced a final, symbolic moment on a California sandlot. The departing CEM students traveled to San Francisco in the summer of 1881 to take a steamship away from their adopted home and back to China. While they awaited that departure, a local Oakland baseball team challenged the Celestials to a game. It’s unclear whether that challenge represented bad or good sportsmanship, an extension of anti-Chinese sentiment or a brief respite from such divisions and discriminations. In any case, as CEM student Wen Bing Chung would later write, “the Oakland men imagined that they were going to have a walk-over with the Chinese.” But the Celestials rose to this almost unimaginable moment and won their final game by a score of 11–8, per a September 4, 1881, story in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The battle between exclusionary and inclusive definitions of American identity has always been with us, but is never more significant than in times of national emergency and trauma. In such moments, we desperately need to remember the stories captured in the PBS documentary — and embodied by the California sandlots that reflect the worst and best of America, in the late 19th century and in 2020.

Featured image: The baseball players of the Chinese Education Mission, 1878 (Thomas La Fargue Papers, MASC, Washington State University Libraries. Used with permission.)

How a Road Less Traveled Led to Baseball’s Boys of Summer

As Americans long for the return of baseball — now indefinitely delayed due to a virus that has shuttered the country — there is no better time to reflect on a soulful interview that sparked one of the game’s most nostalgic human narratives.

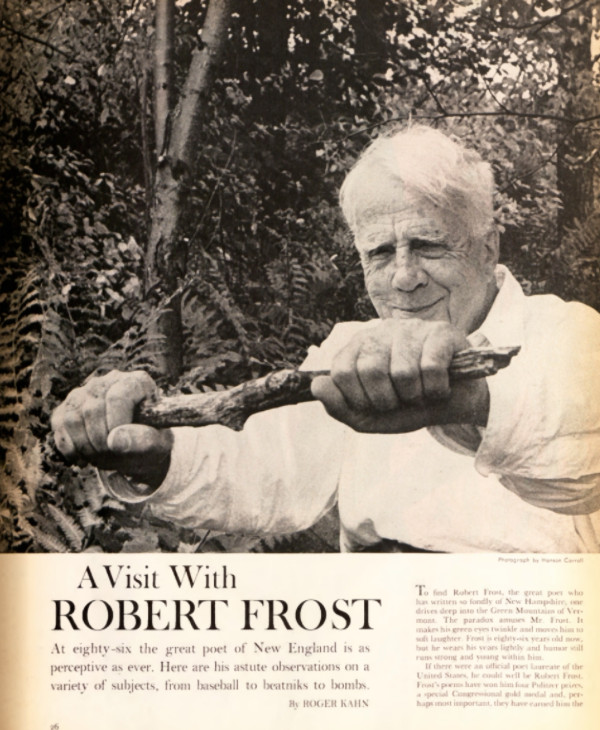

In 1960 The Boys of Summer author Roger Kahn was in his early 30s when he drove along backroads bordering streams in the Green Mountains to spend the afternoon with New England poet Robert Frost. When the sportswriter reached the end of a dirt road, he got out of his car and walked up a hill to Frost’s cabin, where he lived alone, from May until the leaves changed in the fall, when the poet returned to Cambridge.

At the time, Kahn was a celebrated sportswriter who covered the Brooklyn Dodgers for the Herald Tribune in the early 1950s. He based The Boys of Summer on players such as Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, Pee Wee Reese, Preacher Rowe, Carl Erskine, and Roy Campanella. Twenty years after his Boys retired, Kahn caught up with his middle-aged Boys as they struggled through life.

Kahn had met Frost at the Bread Loaf Writers’ conference at Middlebury College in 1951, where the poet pitched to the writer in a summer baseball game with the spine of the Green Mountains in the background. It was there, on that grassy field, when a love for America’s Pastime connected two artists who appreciated the delicate, often brutal plight of the aging athlete.

The World Series was a month away when the 86-year-old snow-headed poet greeted Kahn, wearing blue slacks and a ragged gray sweater. With a face as weathered as the mountain, Frost cut a strapping agrarian frame from years of laboring behind a plow, and daily hikes through the woods, where he conjured phrases about the road less traveled.

The Saturday Evening Post’s “A Visit with Robert Frost” interview drew a response that stunned both Kahn and Frost. Hundreds of letters poured into the magazine from readers. Many enclosed the November 19th feature, asking Kahn to autograph it because they knew he captured Frost in his purest form toward the end of his life.

The Interview

1960 was a tumultuous year. The United States announced plans to send its first wave of troops to Vietnam, John F. Kennedy narrowly won the presidential election, the Soviet Union shot down a U2 spy plane, and Fidel Castro nationalized American oil and other interests.

Xerox introduced the first copier and computers with punch cards were transforming society, yet Frost lived like a pioneer in a previous century. He didn’t have a desk. A ragged row of books lined the shelves of his sparse living room. Frost never learned to type and agreed to the interview on the condition that a tape recorder was not used, feeling the device would disrupt the natural flow of the conversation.

Working on a portable typewriter, Kahn noted that Frost “runs a conversation as a good pitcher runs a baseball game, never giving you quite what you expect.” That afternoon Frost paced around the living room, holding his chin in his hands as he pondered the unfinished business of Russia and Castro, two years before the Cuban Missile Crisis captured headlines. As a poet, Frost spoke of beatniks, loneliness, and the natural, unchanging rhythm of the tides. As a farmer, he explained why he thought it was important for people to be self-sufficient and for every man to know how to live poor.

On the ballfield Frost was a pitcher, and a damn good one who didn’t have a problem with players who slid into base, spikes up. He grew up going to games at Fenway Park and rooted for the Red Sox. His favorite player was Ted Williams, whose last game was eulogized by John Updike on October 22, 1960, in his lyrical New Yorker essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.”

Some of Frost’s most memorable lines compared life to baseball. In a 1956 Sports Illustrated story the poet sat in the grandstand and wrote, “Some baseball is the fate of us all. For my part, I am never more at home in America than at a baseball game.” He also turned this phrase: “Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.”

That afternoon, as the sun lowered over the mountains, Kahn asked his friend, “Is there one basic point to all fine poetry?”

“The phrase,” Frost said, offering this explanation: “A clutch of words that gives you a clutch at the heart.”

A decade later, Kahn clutched readers’ hearts with his true-to-life account of his Dodgers when they hit middle age.

The Last Surviving Boy of Summer

Roger Kahn passed away at a nursing facility in Mamaroneck, New York, on February 6, 2020. As fans from Brooklyn to Los Angeles celebrated his poetic take on baseball, almost all of his “Boys” were gone. Jackie Robinson died at age 53 in 1972, catcher Roy Campanella, who was confined to a wheelchair after a car accident, died in 1993. Pee Wee Reese passed in 1999 and Duke Snider died in 2011, just to name a few.

One particularly resilient player who shared a love of poetry with Kahn and Frost resides in his hometown of Anderson, Indiana.

Ninety-three-year-old Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine returned to Indiana with his wife and family 60 years ago. Kahn affectionately branded Erskine as “Oisk,” based on the way Brooklyners leaned over iron railings at Ebbets Field, rooting for their boy “Cal Oiskine.”

Erskine grew up pitching into a strike zone painted on the side of a barn. He played his entire career with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, from 1948 through 1959. As a starting pitcher, Oisk helped the Dodgers collect five National League pennants, winning the World Series in 1955 against the New York Yankees. At the high point of his career in 1953, Erskine won 20 games and set a World Series strikeout record in a single game on October 2, 1953, in “chilly sunshine” as described by Kahn.

Reporters and writers (like myself) sought out Erskine after Kahn’s passing, asking him questions about the author and his Boys. When I called on a frozen Valentine’s Day, his wife Betty cheerfully answered the phone as the temperature plummeted across the Indiana plains. Erskine was tinkering with something in the garage when he politely came into the house to take my call.

That day he explained why The Boys of Summer will endure as one of America’s most relatable baseball classics. “Roger saw life in more depth than any other beat sportswriter. He drew out the broad personalities of ballplayers in an era of hero worship,” Erskine said.

Kahn always praised Erskine as his most empathetic player. In The Boys of Summer the sportswriter focused on a life decision the soft-spoken Hoosier made to return to Indiana at age 32, staying put to make a better life for his son Jimmy, born with Down syndrome in 1960.

Erskine explained that The Boys of Summer is really two books. “The first part is about Kahn’s childhood, growing up in Brooklyn, where his mother never read him a baseball book, but taught him about Greek mythology, which he applied to ballplayers. The second part is about athletes who age,” he said. The title is derived from the opening stanza of a poem by Dylan Thomas, the struggling Welsh playwright who died at age 39 in 1953. It reads:

I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils.

The Brooklyn Dodgers

The Boys of Summer was met with mixed reviews when it was released in 1972, when Kahn drank heavily and began to resemble Hemingway with a graying beard. Erskine said Walter O’Malley, who moved the team from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, did not like the book because he felt it played on the bad luck and some of the unfortunate circumstances the players faced later in life.

“Kahn exposed this Dodger team that was snake bit – they all had some tough outcomes in life,” Erskine said, recalling that his roommate Duke Snider was not pleased about the way in which he and his family was portrayed.

“I never felt that way. Kahn’s book reflected what real life is like,” he said very matter-of-factly. “It had nothing to do with how many baseballs you hit or players you struck out – you ended up so human that you were just like everybody else.”

Author Gay Talese, who helped define literary journalism, described Kahn’s narrative as a book about ourselves in the October 26, 1972 issue of The Herald & Republican. “It is about youthful dreams in small American towns and big cities decades ago, and how some of these dreams were fulfilled, and about what happened to those dreamers after reality and old age arrived. It is also a book about ourselves, those of us who shared and identified with the dreams and glories of our heroes.”

After The Boys of Summer was published Erskine mailed Kahn a poem by Robert W. Service, entitled “My Masterpiece” about having good intentions but never following through. The sportswriter framed the poem on the wall by the fireplace at his home at Croton-on-the Hudson, New York. The last stanza reads:

A humdrum way I go to-night,

From all I hoped and dreamed remote:

Too late… a better man must write

The Little Book I Never Wrote.

Though Robert Frost, Roger Kahn, and Carl Erskine came from different worlds, the New Englander, New Yorker, and a Midwesterner will forever be united by a love of poetry and baseball. They also help us understand that some of the roughest and most unpredictable roads that life takes us down make us human.

Austin, Texas, writer Anne R. Keene is the author of The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII, being released in paperback on April 21st.

Featured image: © SEPS

Game On! Sunny Weather and Affordable Tickets Make Spring Training in Florida a Winner

For decades, fans have flocked to Florida for a pre-season preview of America’s favorite pastime: baseball. Boasting more than 74 million citrus trees, Florida’s aptly named Grapefruit League squeezes out home runs and plenty of fun from late February through March.

With 15 Major League teams, the Sunshine State is the sweet spot for fans of baseball and saving money. The average cost of a ticket to see the Mets play in New York is $61, but tickets start at $25 to see them play in their spring training facility in Port St. Lucie, 90 minutes south of Cape Canaveral.

East Coast

This spring, West Palm Beach holds the hottest ticket in baseball. That’s because the two teams who share West Palm’s FITTEAM spring training stadium, the Houston Astros and Washington Nationals, both made it to last year’s World Series. The Nationals were last year’s winner, while the Astros won in 2017, the opening year for this rookie South Florida sports complex.

Of course there’s a lot more than just sports to be enjoyed in Palm Beach. The arts are thriving, and a stop at one of the local museums, like Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens or Flagler Museum, is a must. Or take a stroll to gawk at the price tags at the upscale boutiques (think Lilly Pulitzer, Chanel, Gucci) lining Worth Avenue, Palm Beach’s version of Rodeo Drive. Head over to brunch at the grande dame of Palm Beach hotels, The Breakers, for a break from hot dog-and-burgers ballpark fare.

Just 15 minutes north is the northernmost Palm Beach County town of Jupiter, home base for the St. Louis Cardinals and Miami Marlins. Though this sleepy beach town has a population of only 65,000, it’s home to the largest number of professional golfers in the country. With perfect weather, quiet beaches, and magnificent golf courses, it’s no wonder some 35 PGA Tour pros live there, including Tiger Woods.

Take time to enjoy nature by renting a canoe and paddling through the cypress tree-lined waterways of the Loxahatchee River at Riverbend Park, only 10 minutes from Jupiter’s Roger Dean Stadium.

Enjoy the water while dining as well. For a romantic night out, book a waterfront table at the upscale 1000 North. Make sure and ask for a view of Jupiter’s iconic red lighthouse. For more laid-back waterfront dining, head over to Guanabanas, a beloved local hangout known for its live music and casual island vibe.

The Jupiter Beach Resort and Spa is the only oceanfront hotel in Jupiter, making it a great lodging choice. Ride one of the hotel’s free bicycles 15 minutes south to the Juno Beach Pier. A day-long fishing permit at this classic Florida pier is $4 for adults, $2 for kids. Fishing poles, tackle, and bait can be rented on site.

Gulf Coast

Florida’s Atlantic Coast scores with three spring training facilities, but it’s the Gulf Coast that sees most of the Big League action, with teams spread from as far south as Fort Myers up to the Clearwater/St. Pete area.

For Boston Red Sox fans, Fort Myers is a fantasy getaway. Daily direct flights from Logan make it easy to enjoy pre-season baseball at JetBlue Park, known as Fenway South. The Minnesota Twins also call Fort Myers home. Should you want to round out your Fort Myers trip with a little more excitement, it’s a two-hour drive along Alligator Alley to the Atlantic Coast’s Miami or Fort Lauderdale.

An hour north is where the Tampa Bay Rays and Atlanta Braves play. Another 40 minutes north, and you’ve landed in Florida’s “Cultural Coast” of Sarasota, home to a professional ballet, opera, orchestra, ten theaters, and the brand new Sarasota Art Museum. Of course Sarasota’s also home base for the Baltimore Orioles and, a half-hour north, to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Don’t let the pristine beaches and vibrant arts scene of the Clearwater/St. Pete region throw you a curve. It’s also got a winning sports scene, with three Major League teams playing within an easy drive of swanky Sandpearl Resort, located on a magnificent wide stretch of Clearwater’s powdery, white beach. Sandpearl’s on the main drag of Clearwater Beach, where you’ll find hip restaurants, surf shops and the iconic Pier 60 with its nightly sunset party. The Phillies and Toronto Blue Jays play in stadiums twenty minutes from Clearwater Beach. Tampa’s George Steinbrenner Field, 45 minutes away, is home to who else but the New York Yankees.

If you’re game for combining spring training baseball with a trip to Disney World, Universal Studios or other theme parks, the Detroit Tigers play a half hour from Orlando.

For baseball lovers, it doesn’t get much better than this: sunny weather, affordable tickets and the rare chance to get up close with the best players in the Major League. If you’re a baseball fan, you won’t strike out with a spring visit to any of these Florida destinations.

Featured image: Hammond Stadium in Ft. Myers Florida, home of the Minnesota Twins (Evan Meyer / Shutterstock)

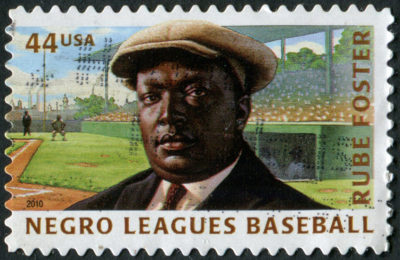

The Negro National League Broke More Than One Barrier

One of the unfortunate truths about everyday life in the America of 1920 was segregation was in full effect. It extended into every avenue of life, from housing to employment to sports. Major league baseball was in its infancy; the National and American Leagues had just come under the control of a single Commissioner of Baseball. Nevertheless, the game wouldn’t be integrated for another 27 years. Black ballplayers had to find a league of their own. While a variety of attempts had been made to elevate such a league going back to the 1800s, an organization with staying power took years to happen. That was the Negro National League, officially formed 100 years ago today.

When it comes to the NNL, you have to start with Rube Foster, known today as the “father of Black Baseball.” Born in Texas in 1879, Foster was already playing for the independent black team, the Waco Yellow Jackets, in his teens. Foster built a reputation over the years as one of the best pitchers in baseball, playing for black pro teams and integrated semipro outfits. By 1917, he’d been a player, a manager, and an owner. His next venture would be even bigger.

In 1920, Foster met with six other team owners to try to build a strong circuit. The result was the first Negro National League. The original teams included the Chicago American Giants (owned by Foster), the Chicago Giants (a separate team), the Cuban Stars, the Dayton Marcos, the Detroit Stars, the Indianapolis ABCs, the Kansas City Monarchs, and the St. Louis Giants. The league provided a stable season for teams, and attendance and earnings went up across the board. Intense competition came from the Eastern Colored League in 1923 and 1924 as that league poached talent from the NNL, but the conflict was resolved when the two leagues came to an agreement that created the Colored World Series, in which their championship teams would compete. A number of other teams would rotate in and out of the league over time, though no more than eight teams would belong at one time.

Rube Foster is featured the Baseball Hall of Fame Biographies series. (Uploaded to YouTube by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Foster took ill after a gas leak nearly killed him in 1925. He began a mental decline and was institutionalized the following year; he died in 1930. The league continued to thrive, though, lasting until 1931 when it was felled by financial problems brought on by the Great Depression. A second Negro National League, known as NNLII, was launched in 1933; the Negro American League launched in 1937 and continued until 1962. By 1947, however, Jackie Robinson had broken the color line for Major League Baseball, leading to an eventual bleed-off of talent and the closing of that league.

In 1981, Foster was admitted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Among the players from the Negro Leagues that made the jump to fame in MLB were such enduring legends as Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella, and Willie Mays. Charley Pride played in the Negro Leagues and then in the minors of MLB before finding fame as an award-winning country singer. The NNLI and all of the other, similar leagues remain a foundational step in the world of sports. They proved that the black community wasn’t just a source of viable sports talent, but a wellspring for coaches, management, and executives. In a strange way, their existence was fulfilled when they no longer needed to exist, helping forge a world in which all players could belong to one inclusive league.

Featured image: Niday Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Cartoons: Play Ball!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Max Porter

August 16, 1952

J. Monahan

August 16, 1952

Ray Helle

August 4, 1951

Rea

July 28, 1951

Larry Frick

July 14, 1951

Schus

September 2, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image and all cartoons: SEPS.

30 Years Ago: Nolan Ryan Threw His 5000th K

He never threw a perfect game. He never won the Cy Young Award. But he dominated baseball across an improbable four decades. He was an eight-time All-Star. He remains the all-time leader in no-hitters. And he is the only player to hurl more than 5,000 strikeouts. He broke that seemingly impossible line 30 years ago this week as a member of the Texas Rangers, and he would continue to add to that gaudy total for four more years. The man in question is, of course, the legendary Nolan Ryan.

Born in 1947, Ryan took up the game at a young age and excelled in high school. He was first scouted by the Mets during a 1963 game. After graduation in 1965, the Mets took Ryan in the 12th round of the MLB draft. From 1965 through 1967, Ryan pitched for the minor league organizations of the Mets, making some Major League appearances in 1966 during late-season roster expansion. He was out for much of 1967 for a combination of Army Reserve service and illness. During his tenure in the minors, as he worked on his control, he posted more than 450 strikeouts.

By 1968, Ryan was firmly ensconced in the majors. He was part of the 1969 “Miracle Mets,” a New York line-up that reversed years of Mets frustration; since its inception in 1962, the team hadn’t had a single winning season. Thanks in large part to a murderer’s row of pitchers that included Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Gary Gentry, Ron Taylor, Tug McGraw, and Ryan, the ’69 team overtook the Cubs as they made their way to 100 wins. Ryan played pivotal roles in two “Game 3” appearances in the post-season. In Game 3 of the National League Championship Series against the Braves, he came on for seven relief innings and his first playoff win; he then saved Game 3 of the World Series in relief, shutting out the Orioles for 2-1/3 innings. The Mets went on to win the World Series.

However, Ryan’s tenure in New York wouldn’t last forever. After being traded to the Angels, Ryan finally got to be a starter. He responded by throwing 329 strikeouts in 1972, which was the fourth-highest total of the century at that point. This set the tone for Ryan’s career; while he was extremely prone to walking (or, on occasion, hitting) batters, his blistering speed and propensity for dominating performances made him a star. He went to the Houston Astros as a free agent in 1980, becoming the first player to earn a million dollars per season. In April of 1983, Ryan broke the all-time strikeout record by retiring his 3,509th batter; just over two years later, he recorded his 4,000th K.

Ryan signed with the Texas Rangers for 1989; he was 42. The seemingly impossible plateau of 5,000 strikeouts was in sight. On August 22, at the top of the 5th in a game with the Oakland Athletics, Ryan faced off against future Hall of Famer Ricky Henderson, whom he’d already struck out previously in the evening (he was 4,998, to be exact). Ryan retired Henderson on a blazing fastball. As the crowd went crazy, Ryan simply doffed his cap, shook hands with some teammates, and went back to work.

Nolan Ryan throws strikeout 5,000. (©MLB)

Over the next four years, Ryan just kept on going. He announced his retirement before the beginning of the 1993 season. Unfortunately, he didn’t get to finish as, two starts short of his expected end date, he tore a ligament in his throwing arm. He was still, at the age of 46, throwing around 98 mph. Upon his retirement, Ryan had set a Major League record for seasons played (27); he was, at the time, also the only remaining player to have made the big leagues in the 1960s.

The numbers for Ryan’s career remain extraordinary. He finished with 5,714 strikeouts; having pitched 5,386 career innings, which means he averaged 1.06 Ks per inning over the course of his entire career. He did, however, give up 2,795 walks, though his career ERA (Earned Run Average) was a rock-solid 3.19. Ryan’s career Win-Loss record was 324-292. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999, his first year of eligibility, with a landslide vote (491-6). Ryan’s number was retired by the Angels, the Astros, and the Rangers, making him one of only a handful of players to have their number retired by more than one team. In his post-playing career, Ryan has become the owner of two minor league teams, served as Texas Rangers president and CEO from 2008 to 2013, and currently acts as executive adviser to Jim Crane, owner of the Astros. Ryan’s son Reid, one of the Hall of Famer’s three children with his wife, Ruth, is the Astros’ president of business operations.

They say that no record is permanent, but Ryan’s crowning achievement might well be untouchable. Number two on the all-time strikeout list, Randy Johnson, retired at 839 pitches behind Ryan. You have to go all the way down to slots 17 and 18 to find the only active players on the list; at this writing, CC Sabathia has 3,068 (and will retire this year after 18 years), and Justin Verlander has 2,934 after 14 years. A Houston Astro, Verlander is currently averaging more strikeouts than innings pitched in his career. Sound familiar? If he continues at his current rate, Verlander might be able to eclipse Ryan . . . in 10 more years. While we wait to see if that mountain can be climbed, we can still sit back in awe and appreciate of one of the greatest to ever play the game.

Featured Image: Nolan Ryan – Tiger Stadium, 1990. (Photo by Chuck Andersen; Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license)

What’s Wrong with Kids’ Sports

Several years ago, I read a book about Harry Emerson Fosdick, who pastored Riverside Church in New York City. It was an interesting book, chock full of curious facts, chief among them that Riverside Church gave Fosdick the summer off each year. I’ve pastored for 35 years and am itching to have a summer off, but when I suggested it to my church, the idea landed with a splat, like a fat man doing a belly flop.

My wife is a school librarian, so has a summer break before hitting the books again the first week of August, which signals the conclusion of summer, even though it officially ends in September. Summer is over once the kids head back to school. If I were the president, the first thing I’d do is raise taxes, which would infuriate everyone, but the second thing I’d do is order schools not to start until the day after Labor Day, and everyone would like me again. Yes, I know what you’re thinking, it would throw off the high school football schedule, but there’s something wrong, something unnatural, perhaps even ungodly, about playing football in August.

While I’m on the subject of sports and seasons, Major League Baseball had its opening day on March 28 this year, the earliest start in history. It will wrap up on or around October 30. That’s just wrong. When I was a kid, we started playing baseball in Barry’s front yard after Memorial Day and wrapped the season up in September, when football began in Marvin Rutledge’s backyard. When football was over, basketball began, deep in the winter, in our gravel driveway, using a hoop my dad nailed to the side of our Indiana barn. Any kid who learns to dribble a basketball on gravel, while wearing gloves, can scarcely believe the utter ease of playing basketball on a hardwood floor. If professional basketball were played on gravel, any random group of Hoosier boys would win the NBA championship every year.

There’s something unnatural, perhaps even ungodly, about playing football in August.

There wasn’t a soccer season when I was a kid because we were Americans and didn’t believe in it, but now soccer is everywhere and has pretty well doomed youth baseball and football. Most everyone else in the world calls soccer “football” in order to trick us into thinking they play football — but they don’t, they play soccer. It’s like me saying I drive a Rolls Royce, when I actually drive a Ford. I don’t trust people who don’t call things by their right name. The third thing I’d do if I were president is outlaw soccer.

As long as I was passing laws about sports, I’d also make it illegal for kids to play on travel teams. I know a 9-year-old kid in Indianapolis whose parents drove him 600 miles to Omaha, Nebraska, so he could play a game of soccer with kids from North Dakota. In the days of old, I was allowed to play sports anywhere, provided I could get there on my bicycle. My parents would no more have loaded me in a car to drive me to a game than they would have quit the Catholic Church to become Buddhists.

We have a lot of problems in our country, what with the national debt, the war in Afghanistan, income inequality, and political division, but I’d be happy if we just started playing the right sports at the right time of year. I have a hunch that if we got that right, everything else would fall right into place.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

The 7 Most Controversial Sports Moves

More than sixty years ago, the Dodgers made a move that’s still hotly debated. It wasn’t about management or personnel; it was about the location of the team itself. Forsaking Brooklyn for Los Angeles, the Dodgers earned New York’s eternal enmity in 1957 (and were followed by another New York team, the Giants, the following year). Team moves happen for a number of reasons (mostly money), but some have a harsher effect on the locals than others. Here are seven of the most controversial team moves in sports.

1. 1945: What Do You Mean the Rams Are from Cleveland?

The Rams franchise was established in Cleveland in 1936; initially, they were part of the American Football League. The following year, they switched to the competing National Football League, and remained until 1945, when they won the League championship. In 1946, the team moved to Los Angeles, based in part on poor attendance. Even the championship game couldn’t fill more than half the seats. Their departure didn’t leave Cleveland teamless; that same year, they got the Browns (named after Ohio State coach Paul Brown).

Upon moving to L.A., the Rams integrated African-American players as a condition of being able to use the Coliseum. With the Browns also choosing the take African-American players, the Rams helped open the League to a whole new segment of athletes and fans. The move also helped establish pro sports in L.A. and set the tone for many future teams to go west.

2. 1957: The Dodgers Move to L.A.

The Dodgers had been in Brooklyn since 1884, breaking the color barrier along the way when Jackie Robinson joined the club in 1947. After a number of rough years, they made it to the World Series in 1956, only to lose to the Yankees. The Dodgers’ majority owner, Walter O’Malley had encountered a number of obstacles acquiring land around New York for a new stadium, and the city of Los Angeles was simultaneously trying to entice teams to come west. After striking a deal with the city that allowed the franchise to build where they wanted, and to also own the stadium (rather than split it with the city), the Dodgers decided to move. One last roadblock came from the National League itself, which told the team they’d block the move unless another team went west. The Giants had been having their own stadium troubles, and it wasn’t long before both teams split for California. The double departure paved the way for the foundation of the Mets in 1962.

In a 2010 interview with WNYC, Michael Shapiro, author of The Last Good Season: Brooklyn, the Dodgers, and Their Final Pennant Race Together, summed up the impact of the move on the city: “What I came to understand is that what the Dodgers were about was a topic of conversation. That, in many ways, is what really makes cities work and what holds cities together . . .I think you can make a really powerful argument that what Brooklyn lost after the Dodgers left was a topic of conversation.”

3. 1960: Alliteration is More Important Than the Number of Lakes

The Lakers actually started with a move when Ben Berger and Morris Chalfen bought the Detroit Gems in 1947 and brought the team to Minneapolis. After a losing season that included the team surviving their plane crash-landing during a snowstorm, then-owner Bob Short decided to move the team to Los Angeles. They became the NBA’s first west coast team; in that inaugural year, star Elgin Baylor and rookie Jerry West led the team back to the playoffs, though they missed the finals by a basket. One interesting wrinkle about the move is that while the name “Lakers” was completely attributed to Minnesota’s 12,000 lakes, the name was preserved in the move, partially because of the nice alliteration.

4. 1982: The Raiders Begin Their Travels

The Oakland Raiders debuted in 1960 as one of the founding teams of the American Football League (which later merged with the NFL in 1970). In 1982, the Raiders moved to L.A., a change that lasted 12 years. At the outset of the 1995 season, they shifted back to Oakland, partially enticed by the city spending $220 million on stadium renovations. In 2016, billionaire casino magnate Sheldon Adelson put together a proposal for a new domed stadium in Las Vegas that would house both the UNLV team and a potential NFL franchise. Adelson held discussions with Raiders owner Mark Davis, who offered to contribute $500 million to the construction of the stadium if Las Vegas would also contribute. When Nevada legislators came through with $750 million in funding, Davis announced his declaration to move, a motion that was approved by the NFL. The Las Vegas Raiders are scheduled to kick off in 2020.

5. 1984: The Colts Sneak Out

After a lengthy and complicated run of cities, team names, and organization changes that stretched from Dayton, Ohio in 1920 through Brooklyn, Miami, Boston, and Dallas, the franchise officially became the Baltimore Colts in 1953. Over the years, conditions at Memorial Stadium continued to deteriorate, with seating, office space, and other amenities being inadequate for the needs of both the Colts and the Orioles baseball team, which shared the stadium. After years of struggle and attempts to get stadium improvements and funds, the city essentially said that they wouldn’t put in the improvements unless the Colts and Orioles signed long-term leases. The Orioles signed for one year; the Colts didn’t sign at all. The city of Indianapolis had begun construction of the Hoosier Dome, hoping to lure a team to the city; when they pitched Colts owner Robert Irsay, it had the desired effect. As the Maryland legislature attempted to pass a bill to seize the organization, Mayflower moving trucks rolled up to the Colts complex and moved the team equipment and belongings out. By the time that the legislature passed the eminent domain bill to seize the team, the Colts had made their way to Indianapolis. They became the Indianapolis Colts with the onset of the 1984 season, earning the enmity of Baltimore forever; however, they did endorse Baltimore receiving a franchise in the ‘90s, which eventually became the Ravens.

For some former Baltimore Colts, the move came as a savage betrayal. Legendary Colts quarterback and Hall of Famer Johnny Unitas severed all of his ties with the Colts organization after the move. He later threw his support behind the Ravens, recognizing them as the true legacy team. Today, a statue of Unitas stands outside M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore, a defiant reminder that some team moves are felt deeply by former players.

6. 2012: The Nets Get Out of New Jersey While They’re Young

The Nets began life as a charter team of the ABA, a presumptive rival to the NBA that debuted in 1967. In their first season, they were the New Jersey Americans. The next year, they moved to Long Island and became the New York Nets; they would win two ABA championships under that name. In 1976, the ABA collapsed and four teams merged with the NBA, including the Nets. They went back to the New Jersey in 1977 and became, of course, the New Jersey Nets. That lasted until 2012. As early as 2005, the Nets had announced their intention to move to Brooklyn, but financing, partnership agreements, and lawsuits among various parties spaced out both the move and the building of their eventual home, the Barclays Center. However, all the obstacles were cleared by 2012, and the Nets, like everyone else, moved to Brooklyn.

7. 2014: Ending 12 Years of Hornet/Bobcat/Pelican Drama

Sometimes, you have a fairly straight team move. Other times, you have a very confusing series of circumstances. The Charlotte Hornets debuted in the NBA in 1988 as an expansion team; that lasted until 2002, when the team moved to New Orleans and became the New Orleans Hornets. In 2004, the NBA placed a new expansion team in Charlotte, which became the Charlotte Bobcats.

An unintended side effect of the Hornets’ residency in their new city came in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when the storm seriously damaged New Orleans Arena. The team was forced to play in Oklahoma City’s Ford Center for the rest of that season and the next season before they could return home. However, their success in OCK allowed the Seattle SuperSonics to successfully move and become the Oklahoma City Thunder.

By 2013, the Hornets decided that they wanted to rebrand and give themselves a name more closely associated with NOLA. Ultimately, they decided that they would become the New Orleans Pelicans. The following year, the Bobcats took back the now-vacant Hornets to become the Charlotte Hornets once again. Today, the Pelicans, Hornets, and Thunder continue to be active, with the Thunder serving as a perennial playoff contender.

Questions remains if the NBA will return to Seattle. Though the Jet City did recently get the franchise for a new NHL team, NBA commissioner Adam Silver says that while he loves Seattle, getting the city another team isn’t a high priority for the league at the moment. Then again, from what we’ve seen, team moves will always be a possibility.

Featured image: The RCA Dome (originally the Hoosier Dome) was built to lure teams to Indianapolis; it was demolished in 2008 and replaced by Lucas Oil Stadium. (Josh Hallett, Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.).

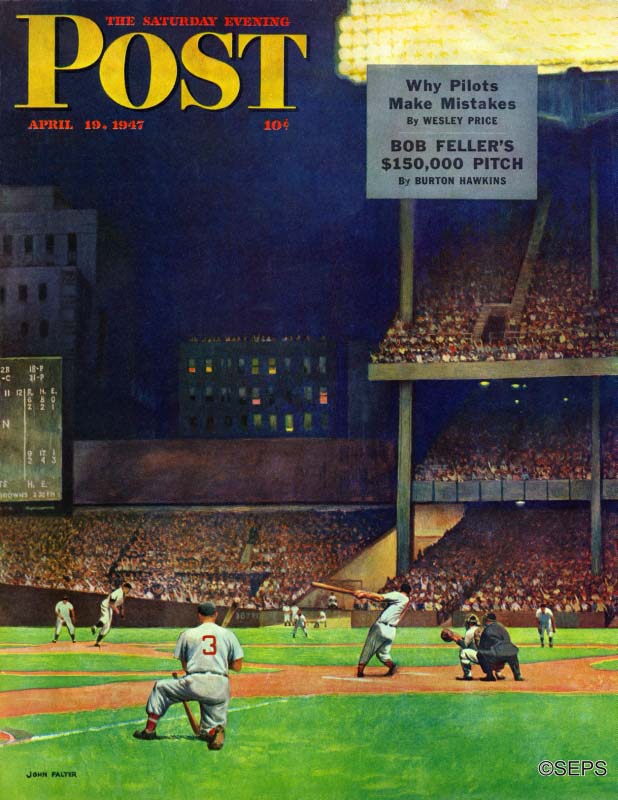

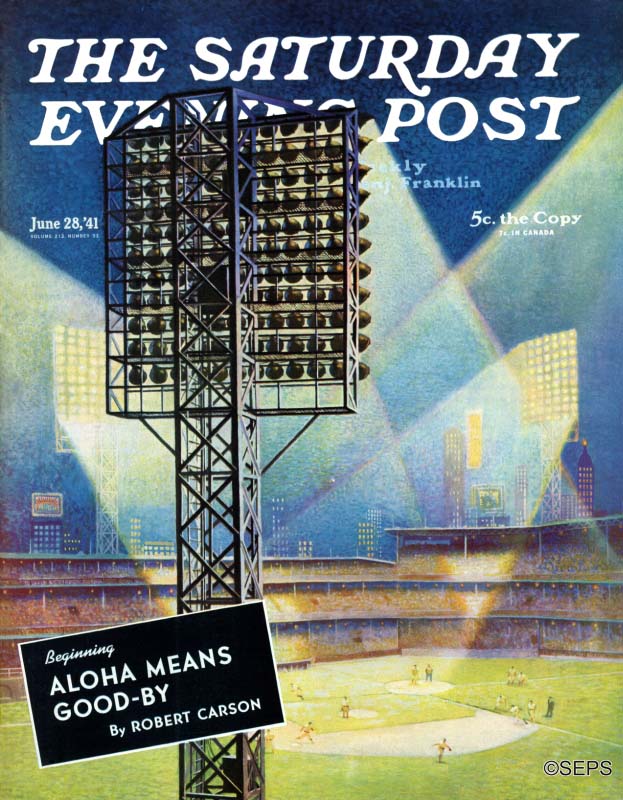

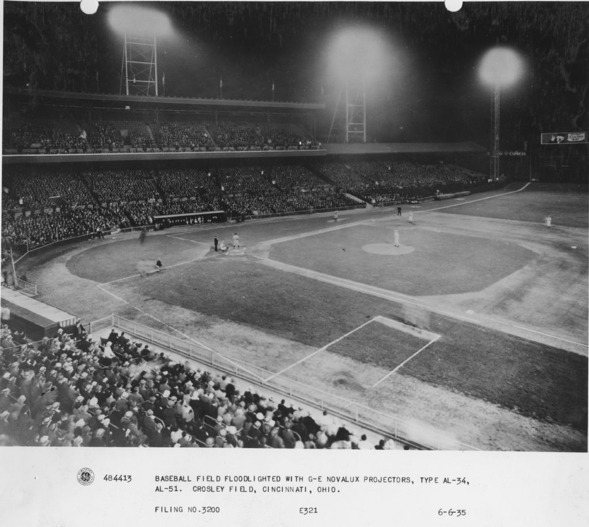

Let There Be Light on the Baseball Diamond

There is something majestic about the electric green glow of the baseball diamond at night, the rush of the cool evening air and the moon bowing its silver face over the stadium rafters. Night games help fans escape the worries of work and life, and The Saturday Evening Post’s artists were there to capture the glory of those first illuminated games that transformed the pastime of baseball.

The first-ever professional baseball game played under “permanent lights” took place May 2, 1930, when a Des Moines, Iowa, team hosted Wichita for a Western League game. The game drew 12,000 people at a time when the team typically attracted a couple hundred fans per game. Those first “nighters” debuted in an era when a tiny fraction of American farms had electricity; lighted games in small towns helped struggling teams survive during the Depression; they allowed farmers, factory workers, teachers, civil servants, and policemen to attend games after an exhausting work day when the entire country was trying to rebuild the economy.

On the evening of May 24, 1935, the Cincinnati Reds were scheduled to face the Philadelphia Phillies in Major League Baseball’s first night game, played under lights installed by the City at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Initially, some baseball executives frowned on the prospect of America’s best baseball being played under artificial lights. In Washington, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt punched a button from his desk firing more than one million watts of electricity to bathe the field in light. Ford Frick, President of the National League, threw out the first pitch of the game before 20,422 fans who munched on hot dogs and popcorn and watched the Reds beat the Phillies 2-1.

Today, more than 80 percent of all Major League Baseball games are played after the sun goes down.

Memories of those games are fresh in the minds of Big Leaguers who came up in the ’40s and ’50s. Philadelphia Phillies’ pitcher Robert “Bob” Miller, age 92, is a U.S. Army veteran and one of two surviving members of the “Whiz Kids,” the young team that unexpectedly made it to the 1950 World Series against the New York Yankees. Thinking back to those nighters, Bob says the lights were pretty darn good. “You could see a pitch … catch a fly ball.” But when the sun went down in cities like San Francisco and Philadelphia, it got cold pretty fast, and he would put on an overcoat. The schedules changed too. Bob recalls, “The team ate dinner around 2. After the game we may have had a beer or two. Then it was midnight and I loved every minute of it. After all, I was in the Big Leagues and how can you not like that!”

Feature image: The first Major League night game , in Cincinnati, Ohio. (GE)

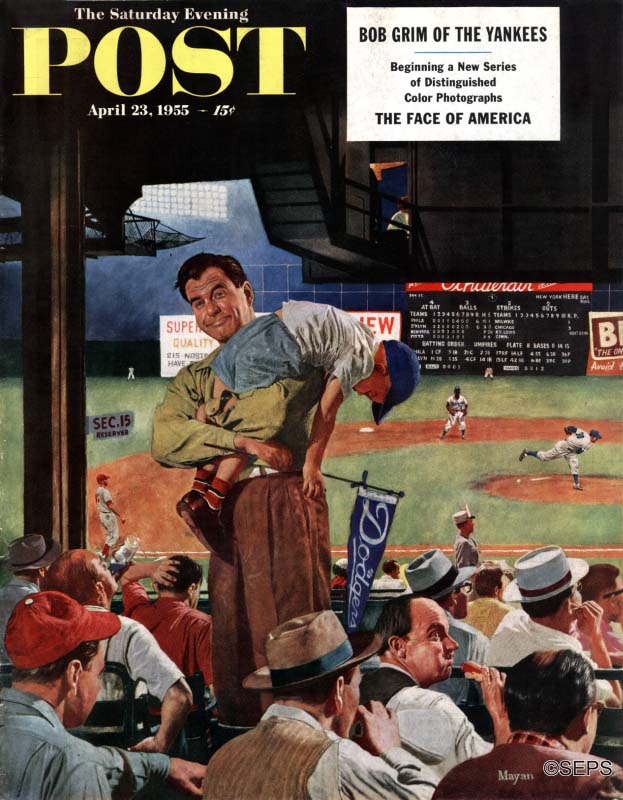

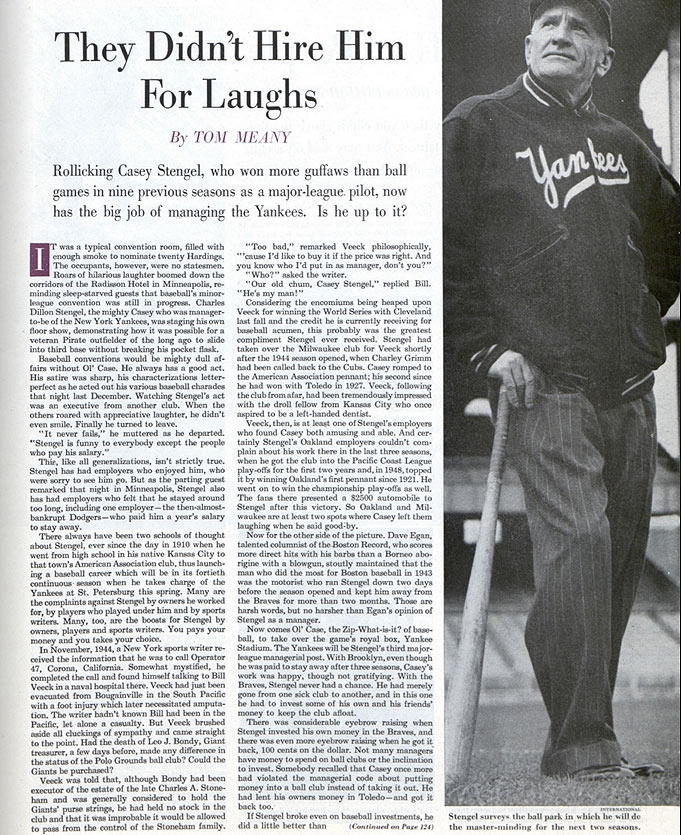

Casey Stengel: They Didn’t Hire Him for Laughs

When Casey Stengel became manager of the New York Yankees in October of 1948, most people weren’t too excited about the new hire.

The previous manager, Bucky Harris, had been wildly popular, having taken the Yankees to the World Series championship in 1947. They finished third in 1948, but it was rumored that the reason Harris was fired was that he wouldn’t give general manager George Weiss his home phone number.

When Stengel joined the Yankees, his career as a manager for the Brooklyn Dodgers (1934–1936) and Boston Braves (1938–1943) was considered lackluster. Boston newspaper columnist Dave Egan remarked that Boston’s 1943 team should have considered themselves lucky when a taxi driver ran Stengel over two days before the season opener, fracturing his leg and keeping him away from his duties for almost two months.

When a profile of Stengel appeared in the March 12, 1949, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, writer Tom Meany noted that the Yankees weren’t so sure about Stengel, either: “There has been considerable speculation over the reaction of the old-line Yankees to the appointment of Stengel. … It will be novel, to say the least, for them to be directed by a manager who thus far has gained more fame by his humor than by winning pennants.”

Indeed, Stengel’s most notable traits at the time were his quips and quirky conversational style. Meany wrote, “Although always an entertaining conversationalist, Stengel has a habit of wandering from his point, like a dog turned loose in a rabbit patch.” Stengel once observed that “the secret of successful managing is to keep the five guys who hate you away from the four guys who haven’t made up their minds.”

What Meany couldn’t have guessed as Stengel started his stint with the Yankees is that Stengel would lead the team to five consecutive World Series wins (1949–1953), the most consecutive wins ever by a major league baseball team. What Meany did predict was Stengel’s drive to succeed, writing, “Nine years of trying to win with has-beens and never-weres left its mark on Stengel. He became a desperation manager, like a fellow playing the races with the rent money.” That desperation may have led Stengel to develop some of his unique strategies, including platooning, leveraging pitchers, and getting creative with lineups.

Meany concluded that “despite Stengel’s critics, who think he does it with wisecracks, baseball jobs such as managing the Yankees are handed out on the basis of what you know rather than whom you know. Baseball observers think Casey knows a lot.”

Turns out, he did.

Featured image: Edited image from Baseball Digest, front cover, October 1953 issue (Wikimedia Commons / public domain)

Wiffle Hall of Fame

In the annals of Wiffle Ball, that breezy June afternoon in 1966 will forever remain etched in gravel.

My brother Martin stood on the pitcher’s mound, a dimly defined region between first base (the end of a downspout at the rear corner of our house) and third base (a piece of wood). It was just the two of us.

“Up at bat is Bill Newcott,” he said, narrating the game from the playing field. “He looks like he’d really like to put one out of here today. Here comes the pitch …”

A hollow thud echoed through the neighborhood, the sound of a plastic ball catching the sweet spot of a plastic bat, not that inconsequential “click” you heard most of the time. No, this was a good, throaty, slugger’s “whoomp.”

“Holy cow!” Martin exclaimed in homage to New York Yankee announcer Phil Rizzuto.

In a graceful arc, the ball headed up toward the canopy of trees that overhung the field in those days. But instead of becoming tangled in the branches, the sphere found its way through a gap in the trees and continued its trajectory up… up…

“Holy cow!” Martin exclaimed again, pointing down the driveway as the ball slapped up against the wall of the apartment house all the way across the street!

A hollow thud echoed through the neighborhood; the sound of a plastic ball catching the sweet spot of a plastic bat.

We did our best to measure the distance of that moonshot, putting one foot in front of the other and counting off our steps. Initial estimates placed it at 300 feet. Subsequent measurements trimmed the actual distance to 110.

There is a certain melancholy attached to an athlete who peaks so young (in this case, age 11). Looking back now, the ensuing 50 years or so have offered their share of successes, but few moments have made my heart stand still the way it did as I stood there in a scratched-out batter’s box, having a Mickey Mantle moment.

Our Cathedral of Wiffle Ball on Sunnyside Avenue in Dumont, New Jersey, was in reality an unpaved driveway, 12 feet across at its widest spot, nestled between a small tree-studded lot (“the woods”) and our house. The garage at one end of the playing field served excellently as a backstop, except when the ball was fouled back over the garage and into our neighbor’s backyard. This was patrolled by a large, unfriendly dog, but we had rules for that: If the dog ate the ball, the batter was out. If the dog merely mangled the ball, the batter’s team lost an out the following inning.

Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball followed this tradition of clear, concise rule-making throughout its golden era, which lasted from 1963 to somewhere around 1973. In that decade, legends were born. Dynasties rose and fell. Windows were broken (not so much in the early days, but later, as adolescence set in, even with a plastic ball one mighty swing could do real damage to a pane of glass just 20 feet away).

The distance from home plate to the first base downspout was 15 feet. If a car was parked in the driveway, the front license plate was second base; otherwise a rock, a piece of wood, or a scratched-out box would do. Third base was the end of a board my father had half-buried along the edge of the driveway in a futile attempt to block the garbage and dead leaves that blew over from “the woods.”

Anything that landed in the street was a home run. Anything that landed in the driveway was fair, and anything that landed off of it was not. This unique ground rule led to us becoming expert in driving balls to straightaway center field, but it caused me some consternation when I endured an abbreviated career playing for my town’s Babe Ruth League.

“Newcott, you hit every ball up the middle,” my coach barked. “Can’t you pull it once in awhile?”

“No, coach, I can’t,” I admitted, heading back to the bench where I spent most of my time.

It should be noted that the Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball league did not often use official Wiffle Balls — the variety with the holes in one end that supposedly give anyone the ability to throw a curve ball that will write your name in midair. Hitting was the name of our game, and the Wiffle Curve Ball just didn’t travel far enough. As sluggers, we preferred cheap hollow plastic balls, the kind that came four to a bag.

Also, the drawback of using actual Wiffle Balls became evident one autumn day when I popped one up and it became impaled on an overhanging branch. We had no rule for that, so we suspended play and started a new game with a new ball.

On a winter’s day a few months later, when he must have had nothing else to do, Martin threw rocks at the thing until it came down and he caught it. I was inside watching TV when he dashed in from the yard, holding the ball aloft. “Out!” he yelled. By mutual agreement, that ended the game.

While Martin and I were the primary figures in the Sunnyside Avenue Wiffle Ball league and most often played one-on-one, there were a number of journeyman players who drifted in and out of the lineup. We had to admit that when the three Richards brothers from across the street participated, it almost looked like we were playing an actual game and not simply two kids engaging in some sort of baseball-inspired Kabuki.

The ultimate proof of strength and championship ability was home run production. The author was the all-time home run king of the league, although in his fading years he was overtaken and ultimately surpassed by his younger brother (to whom he taught everything he knows). In 1966, at age 11, the author hit 52 home runs, including the aforementioned Longest One on Record.

Undoubtedly the most important regulation in the league was the now-famous “interference” rule. If a ball was headed fair but was then knocked foul by a branch, the batter could yell “interference” and it would be a dead ball and he got a do-over. If the ball was headed foul and then knocked fair, the fielder had the option of yelling “interference” or attempting to catch the ball. However, he had to yell “interference” before the ball hit the ground. Many a tussle and broken plastic bat resulted from arguments on this point. In the name of sportsmanship, the rule was eventually ditched.

A few other rules we relied on:

- “Invisible Men” often served as runners, since there were rarely enough players to occupy the bases. (If a fielder touched second before the hitter reached first base, the Invisible Man from first was out.)

- If a foul ball landed in the swimming pool (installed 1969), the batter was out.

- If the pitcher threw the ball through one of the broken windows of the garage, it was a wild pitch and the runners advanced.

The years passed, and in time, our bodies became unfit for driveway Wiffle Ball. First base was suddenly a mere two strides away from the plate. Also, the miniature plastic bat looked small and silly in our hands. I moved to California in 1977, and my parents moved to Buffalo the following year. In 1993, we had a family reunion and played Wiffle Ball in a field near my house; all five Newcott kids, our spouses, and even my 85-year-old dad. It was fun, but more than once Martin and I caught each other’s gaze and smiled wistfully. It wasn’t the same.

Occasionally I drive through my old neighborhood. I get out of the car and stand at the end of the driveway, recalling the glory days when kids could be heroes. And I find myself singing to myself that old Frank Sinatra song, “there used to be a ballpark, right here.”

Bill Newcott is the movie critic for The Saturday Evening Post.

This article is featured in the March/April 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Swinging for the fences: Author Bill Newcott showed he had not lost his form during his family’s 1974 Old Timer’s Day festivities. After years of shattered glass, the garage window panes had long since been boarded over. (courtesy Bill Newcott)

Cartoons: Play Ball!

Clyde Lamb

September 18, 1948

H. Middlecamp

July 17, 1948

Tom Henderson

July 10, 1948

Bob Gallivan

June 26, 1948

Tom Henderson

May 29, 1948

Irwin Caplan

October 16, 1948