Bring Them a Figgy Pudding

Having grown up in a small town and regularly attending its Methodist church, it has never occurred to me that a church service could be crowded or, heaven forbid, full. So when I marched into the Unitarian Universalist Church to attend a winter solstice celebration, promised to be “a night that ranges from meditative to raucous,” I was shocked to learn that there was no room at the inn.

Like the three wise men, I had come bearing gifts — a homemade figgy pudding — and like the virgin Mary, I was turned away. I was about fifteen minutes late, and the greeter was only acting in accordance with the city fire code. And it wasn’t a real figgy pudding.

Similarly to Joan Didion, I think of myself as a “can-do” person. Particularly around the holidays, I am inspired to open my oldest bottle and bake up seasonal confections in the traditions of the days of old. Last year, I made a fruitcake. This year, I planned to tackle the elusive figgy pudding.

The only problem is that figgy pudding appears to be little more than a holiday lyric.

At least, that seems to be the case with this dessert that everyone sings of and no one actually eats. The archives of The Saturday Evening Post make no mention of a popular dish called figgy pudding, but NPR explored the history of figgy pudding several years ago, and they maintain that it is, indeed, real and edible. The recipe they provide calls for beef suet, five to six hours of boiling, and — ideally — four to five weeks of aging. If you have that kind of time and enterprise, then, by all means, whip up the Victorian treat during a movie marathon.

Instead, I opted for a bread pudding recipe from the January 28, 1913, issue of this magazine. In “Old Bread in New Puddings,” Elisabeth Irving makes a convincing, if dubious, case for making bread pudding from all of those leftover bread crumbs that would be found in the early century home: “It seems to us that if, instead of the inevitable pie and cake so constantly served on some farm tables, the farm housewife, when concocting desserts for her family, would oftener utilize some of the fragments of bread that usually go to waste, in connection with the abundant milk and eggs always to be had on the farm, there would be better nourished bodies and less stomach trouble, and consequently fewer doctor bills.”

Having made the famous Thanksgiving classic, persimmon pudding, recently, I was in abundance of buttermilk (make Eva Powell’s award-winning recipe with very ripe persimmons, if you can get them, and serve it with whipped cream and a dusting of cinnamon), but I haven’t found myself baking loaves of bread lately, so I dried bread crumbs from store-bought baguette. I made the “Chocolate Bread Pudding” (see the flipbook below) from our archives, but I made a few changes, rendering Dark Chocolate Bread Pudding with Blueberry Preserves and Mandarin Orange Meringue.

The blueberries were an accident. I grabbed a jar in haste at the grocery store, thinking it was cherry preserves. When I arrived at home and discovered my mistake, I decided I would have to live with it. If medieval homemakers could mix meats and fruit, then I was allowed to get creative with dark chocolate.

The beauty of bread pudding is, just as Elisabeth Irving puts it, “there are so many possibilities, for the ingenious cook who takes a little trouble that there is no excuse for lack of variety in that direction.” Bread pudding is like sweet stuffing. You can throw anything you’d like into it. If you want to toss in dried figs (first cooked in brandy) and sing about your perfectly appropriate pudding, you can!

After my pudding and I were denied entry to the pagan celebration, I took it to a friend’s Christmas party. I had a vision of waltzing in with my festive dish, dousing it in brandy, and setting it aflame as the other party guests applauded my culinary achievement. When I arrived, the house was so packed full of people I could barely squeeze through to the dessert table. I searched for my friend, a student of performance art at the New School back home for the holidays, and ended up striking conversations with various lawyers while keeping one eye on my untouched bread pudding.

Would the other guests love it? Hate it? Would they wonder aloud who possibly could have created the dark chocolate bread pudding, announcing the taste of fruit and zip of citrus that ties it together so nicely?

When I finally found my friend, he introduced me to other, college-age, interesting people. They were involved in theatre or fashion and had the excited spark of students in their early 20s. One of them was terribly fit, and I learned that it was because he was a tightrope performer at École nationale de cirque in Montreal hoping to join Cirque du Soleil. My friend told me he was going to perform a piece of performance art in ten minutes. “It’s a very interactive performance,” he said. Oh no, I thought.

I hadn’t the time or the patience with the crowd to make my way back to the pudding to see if it had been devoured, perhaps fought over. My friend gave his performance, a combination of audience interaction and audio recorded on a day he had zip-tied himself to a fence in Manhattan. We maintained eye contact with strangers for ten minutes and shared how we felt about the sounds of our own names. Then he instructed us to find a spot around the room and to lie down. He told us to hold hands with the person closest to us. This is taking longer than I expected, I thought. I wonder how that pudding is doing. The person closest to me was the tightrope acrobat. I hadn’t said much to him up until that point, but we followed directions, grasping hands while lying in opposite directions.

Immediately after assuming a grip, I realized it was the most uncomfortable position possible. But it would also seem too imposing (or too intimate?) to spend time finding a better position for my hand. Minutes passed as the audio played. I realized I was slightly hovering my hand off the floor quite awkwardly, and it was starting to go numb. My partner stayed perfectly still, so I didn’t want to break anyone’s concentration. Of course he’s excelling at this, he’s an acrobat, I thought. He’s used to these kinds of endurance tests. Then I realized my palms were sweating. On the audio, a street drummer played an entrancing rhythm on buckets and bells while the wind ripped across the microphone. I wanted to check on the pudding.

Afterwards, I poured a glass of wine to the brim and headed to the dessert table. The pudding was gone! And its plate washed and drying in the kitchen. I would never know if the serving dish had been desperately licked clean by lawyers’ children who would be forever haunted by the mystery dessert they could never find again. Then, I realized I didn’t even know for myself whether the bread pudding was as delectable as I imagined, because I never got a piece. I chewed some peppermint bark and said my goodbyes, preparing for more intrusive thoughts about the best bread pudding I never had.

Dark Chocolate Bread Pudding with Blueberry Preserves and Mandarin Orange Meringue

- 2 cups bread crumbs

- ¾ cup sugar (plus 1 cup for meringue)

- ¼ cup molasses

- 4 tbsp butter

- 1 pint milk

- 1 pint buttermilk

- 4 eggs

- 6 tbsp dark chocolate powder

- Blueberry preserves (or raspberry or cherry)

- Pinch of salt

- 1 mandarin orange

Directions

- Melt butter, and stir in ¾ cup sugar. Add in molasses, milk, buttermilk, dark chocolate powder, bread crumbs, and salt.

- Separate egg yolks and stir them into the batter, taking care that the batter is not too warm from the melted butter. Save the whites for the meringue.

- Pour into a baking mold, and bake at 300 F for about 2 hours.

- Make meringue using the egg whites, 2 tbsp of juice from the mandarin orange, and 1 cup of sugar, added slowly.

- Once it is set, flip the pudding out of the mold. Using a filling syringe, pipe blueberry preserves into the pudding through the top, making your way around. Cover the top with meringue piled high. Broil in the oven, watching closely, for a few minutes to brown the meringue.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Rockwell Video Minute: Rockwell and Charles Dickens

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

Hallmark’s Formula for a Very Sappy Christmas

In the new Hallmark movie Holiday Date, Brooke has been dumped just before Christmas by her sleek, professional beau — he’s “going to be really busy with this project” — and her English-accented boss poo-poos her classic clothing designs in favor of more “cutting edge” fashion. Joel is an actor up for a big role playing a small-town hero, and their friends think it’s a good idea for Brooke to take him back to her hometown, Whispering Pines, for the holidays to pose as her boyfriend. “I can’t believe we’re doing this,” Brooke says as they cruise across the wintry landscape in a baby blue Mini Cooper. He lets out a fake boyfriend chuckle: “I know, it’s crazy, isn’t it?”

It’s not that crazy, though.

At least, not in the Hallmark cinematic universe. The phony boyfriend or girlfriend plot device also appears in Holiday Engagement, The Mistletoe Promise, Hitched for the Holidays, A December Bride, Snow Bride, and A Christmas for the Books, to name a few.

By now, Hallmark is a well-known holiday movie machine. This year is the 10th anniversary of Hallmark Channel’s “Countdown to Christmas,” a two-month-long nonstop marathon of garland-wrapped, hot cocoa-fueled, gentle holiday romance. The greeting card company — through their subsidiary Crown Media — has effectively cornered the market on Christmas cable programming for younger and middle-aged women, and this year they’ve released 40 new Christmas-themed made-for-TV movies between their networks Hallmark Channel and Hallmark Movies & Mysteries.

This past summer, I visited my parents, strolling into my childhood home and beholding — on their new flat screen TV — a cheesy Christmas movie. In July! I accosted my mother, wondering how she could live with herself watching Hallmark Christmas movies during tomato season. But they were running a special marathon, “Christmas in July,” and she wasn’t alone in cozying up to holiday movies with the air conditioner running. What could possibly be the appeal of these movies? I thought to myself as we sat through the third one in a row.

“If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all” was never more applicable than to the Hallmark oeuvre. (2014’s A Cookie Cutter Christmas displayed an eerily self-aware title.) Any fan of the franchise is well aware of the formula: a man and woman meet under awkward circumstances, stumble slowly toward romance, and finally share a brisk kiss under the glow of a thousand Christmas lights. There are recurring themes, like the virtues of slower, small-town life over the cold, hectic city, or the importance of listening to your heart and following where it leads (incidentally, it leads an inordinate segment of Hallmark characters to stake out their lives in pastry bakeries and tree farms). The most important virtue, however, is the love of Christmas and belief in its fateful magic.

The company has fashioned its own film genre out of wealthy suburban culture and happy endings, but it didn’t always used to be that way.

In fact, the last decade or so of Hallmark’s television programming is a departure from their media legacy. Since the dawn of broadcasting, the company has been known for culturally significant, acclaimed drama. Their pivot to feel-good seasonal romance says as much about the Hallmark brand as it does about us, the viewers, and what we hope to gain from watching them.

In the 1930s and ’40s, after a few decades of success selling greeting cards and wrapping paper, the Hall brothers of Hallmark decided to get into the radio game. They began by sponsoring shows like Tony’s Scrapbook, a folksy poetry program that a 1932 Time magazine review claimed was “regarded by a shuddering minority as the most offensive broadcaster on the air” for the host’s sentimental, rustic demeanor. Hallmark also sponsored Meet Your Navy and Radio Reader’s Digest as the company navigated national growth.

Then, in 1948, Hallmark went off on its own with Hallmark Playhouse, a radio drama program to replace their partnership with Reader’s Digest. Hallmark Playhouse was to be a new kind of show, one that delved into the annals of literature to find worthy, sometimes obscure authors and titles for dramatic readings, with author James Hilton, and later Lionel Barrymore, as the host. Hallmark Playhouse broadcast readings of Edna Ferber, Carl Sandburg, and Ring Lardner with stars like Irene Dunne, Bob Hope, and Gregory Peck lending their voices. Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Devil and Daniel Webster” and Rose Wilder Lane’s Free Land (both found in the pages of The Saturday Evening Post) were also dramatized on Hallmark’s acclaimed anthology show.

On December 22, 1949, “The Story of Silent Night” aired, dramatizing the origin of the Christmas song, with a children’s choir, sound effects, and original music by Lyn Murray. Media scholar John V. Pavlik wrote about how the episode underscored “the extraordinary resources, intellectual capital, and pure talent that went into creating a program such as the Hallmark Playhouse, a program that consistently produced the highest levels of production quality and value.”

Two years later, in August 1951, founder J.C. Hall excitedly announced to the company that Hallmark would “try our hand at television.” Corporate sponsorships of television dramas were common. In Texaco Star Theater, Milton Berle was hosting an unpredictable hour of comedy and music, and Goodyear (or Philco) Television Playhouse brought original drama to the screen from up-and-coming writers and actors. The first Hallmark Television Playhouse broadcast was on NBC on Christmas Eve, 1951, and it was unlike anything seen on American television before. Amahl and the Night Visitors was a live opera, composed for television by Pulitzer winner Gian Carlo Menotti, telling the story of the three wise men from the point of view of a young peasant boy.

Hallmark Television Playhouse (and later Hallmark Hall of Fame) aired weekly for several years, before scaling back to monthly, then seasonal, episodes. Throughout the ’50s and ’60s, the series became a unique television event, bringing classic stories and big actors to the small screen. Maurice Evans played Richard II, Judith Anderson played Lady Macbeth, and Christopher Plummer and Julie Harris starred in A Doll’s House. Hallmark claims that more people tuned in for the 1953 broadcast of Hamlet than had cumulatively seen the play performed on stage in 350 years.

Although many programs from the “Golden Age of Television” disappeared, Hallmark Hall of Fame held strong. The format and content changed, but the series continued to present classic stories and problem dramas on primetime TV with big-name actors. In 1986, James Garner and James Woods starred in Promise, a drama depicting the arduous task of caring for a sibling suffering from schizophrenia. Far from saccharine, Promise holds up as a sensitive portrayal of the toll of mental illness on relationships. The film got a DVD release, but you won’t find it, or virtually any other Hall of Fame movies, on any streaming service.

In a 2009 CBS story on the enduring legacy of Hallmark Hall of Fame, Ron Simon, of the Paley Center, said “Hallmark has been around almost the entire history of American broadcasting, it’s one of the few institutions that sort of remain unchanged from postwar America into 21st-century America.” The Hall of Fame series has won 81 Emmys, the most recent of which was 2009’s The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler.

Their ratings began to falter however, and in 2011, CBS dropped the program. Hall of Fame found little success at ABC, and, eventually, Hallmark moved the franchise over to their own cable channel, where they’d already been experimenting with a new strategy for made-for-TV movies that didn’t require period costumes, classic scripts, or much dramatic conflict at all.

The most recent Hallmark Hall of Fame release is called A Christmas Love Story. Starring Kristin Chenoweth and Scott Wolf, the story follows an ex-Broadway star who finds love, and inspiration for a new song, while teaching a children’s choir in New York City. Aside from some long-lost-parent drama, the film is nearly indistinguishable from Hallmark’s other holiday fare, with all of the same Christmas glitz and cloying courtship as A Shoe Addict’s Christmas or Two Turtle Doves.

Michelle Vicary, the executive vice president of programming for Crown Media, recently told Parade magazine that “People need to feel good and they need comfort, so, it’s an honor to bring that to people.”

Even though we’re familiar with all of the actors, we can predict the plot, and we might even recognize that gazebo in the final scene that’s lit up like an oversized tanning bed, we keep watching, year after year. And Hallmark knows it. They hope to capture the hearts of 100 million viewers this year over last year’s 85 million.

Hallmark has expanded its holiday offerings, and last year they released the Hallmark Movie Checklist App to help viewers keep track of the listings. This year, Hallmark sponsored the first Christmas Con in Edison, New Jersey, where fans could meet some of their favorite Hallmark stars and bask in some curated Christmas cheer.

Online, Facebook groups, numbering in the tens of thousands, are filled with Hallmark fans — mostly women — posting about their favorite movies. Many of their interactions muse on the movies’ similarities or the attractiveness of male leads. Others share photos of their decorated Christmas trees or a serendipitous snowfall right before the holidays.

I talked to Jennifer, 36, from Durham, North Carolina who moderates a subreddit group dedicated to Hallmark Movie fans. “I used to like watching Lifetime movies,” she says, “but they started to get a little too ridiculous and dramatic, so I had to walk away. I started watching Hallmark Hall of Fame movies at night when I couldn’t sleep, and they just made me feel at home, no matter how depressed or sad I was.”

Jennifer was orphaned at a young age, so she says she enjoys watching a family in a Hallmark movie having a nice holiday. Also, her 12-year-old son is autistic, and she says the movies inspire her to make Christmas special for him by doing things like baking cookies and decorating a tree. “I just love how sappy Hallmark movies are,” she says. “Everything is always alright at the end, which is just the opposite of real life.”

For Hallmark, the promise of comfort might be increasingly more difficult to keep.

Hallmark has faced criticism about the lack of diversity in their casting, and, just recently, they came under fire for taking down ads that featured two women kissing (Hallmark has since reinstated the ads and apologized). In the most current incarnation of Hallmark’s made-for-TV world, divisive politics don’t exist, along with poverty, mental illness, or war. The worst fate a Hallmark character could succumb to is working late on Christmas. Hallmark’s preoccupation with manicured small towns and contrived joy begs the question of whether they’re selling nostalgia or fantasy.

In Holiday Date, when Brooke’s pretentious European boss tells her she should design edgier clothing, the winsome blonde snaps back: “You know, the history of fashion shouldn’t be ignored. There’s a lot to be learned from the past and how it shapes who we are.”

“Of course that’s true! But you’re only inventing a past that comforts you!” I shouted at the television. And my mom told me to shut up and enjoy the movie.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Eight, er, Nine Tiny Reindeer

Today, we all know the names of Santa Claus’s nine flying reindeer — or at least we think we do. But what is behind those names, and which ones have changed over the last 200 years?

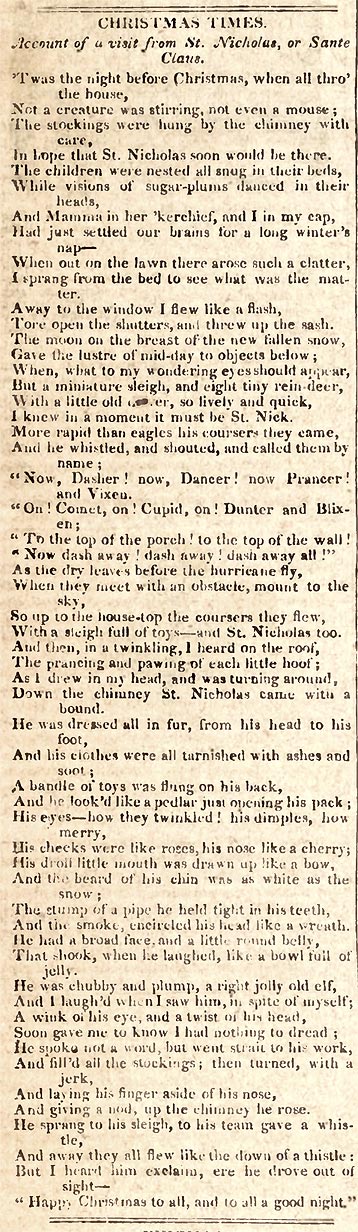

January 7, 1826

The names of eight of those reindeer first appeared in the poem we know today as “The Night Before Christmas.” It was first published anonymously on December 23, 1823, in a newspaper in Troy, New York and became an immediate hit that was published and republished for years in papers across America under the title “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The Saturday Evening Post even printed it in its January 7, 1826, issue.

But the man responsible for penning the poem remained a mystery until 1836, when Clement Clark Moore, a Bible professor from New York City, took credit for it. He even included it in a volume of his poetry published in 1844. However, the family of another New Yorker, Henry Livingston Jr. — who died shortly after the poem’s first publication and before Moore took credit — have long claimed that he was the poet. More recent research has reinforced that argument.

Regardless of who wrote the poem, it is the first to include Santa’s reindeer and call them by name. They weren’t names passed down from Old World folklore, but were created by the poet. Whether they were chosen for their meanings, their colloquial connotations, or simply for their rhythm and rhyme, we’ll never know. But the names do have some history, and they perhaps aren’t all exactly as you remember them.

Dasher

A dasher is simply one who dashes. Dash appeared in Middle English as dasshen in the 14th century, probably from the Middle French dachier “to drive forward.” Two types of “dashing” appeared in English at about the same time: There’s the “moving quickly” dashing, as in “dashing off to the store,” and there’s the “striking suddenly and violently” dashing, as in “being dashed against the rocks.” The poet probably had speed in mind when he chose this name — it is, after all, a poem for children — but some writers do have a knack for slipping in opaque little adult-themed jokes in their children’s stories.

If there is an adult insinuation here, there’s an even more frightening possibility. By 1800 — meaning it likely would have been known to the poet — dash was also being used as a euphemism for damn. Considering that Santa Claus’s raison d’etre is to be extremely judgmental of children, having a reindeer that hints at the ultimate naughty list wouldn’t be out of place. (It’s unlikely, sure, but not implausible.)

Dancer

Dance — from which the name Dancer is formed — has an unexpectedly muddied history. We know it entered Middle English in the 1300s as dauncen, from Old French dancier “to dance,” but that’s where certainty stops. Though French is well known as a Romance language — that is, it’s derived from the language of the Roman Empire — dancier isn’t derived from Latin: The Latin word for “dance” is saltare. Etymologists aren’t certain exactly where dancier came from; it’s possibly from an old Frankish dialect that predates the expansion of the Roman Empire into northern Europe.

Prancer

The history of prance is similar to that of dance. It, too, appeared in Middle English in the 1300s, as prauncen, and its ultimate source is debatable. Some theories about its provenance include the Middle English pranken “to show off,” from the Middle Dutch pronken “to strut, parade” (and the source of our word prank), or from a Danish dialect word prandse “to go in a stately manner.”

Regardless of where it came from, the word was originally used to describe horses — and it eventually found its way, in this poem, to a different hoofed animal.

Vixen

Going back to Old English fyxen, vixen is a feminine form of fox. Today, vixen is more commonly used to describe a sexually attractive woman — especially on the big screen — but that extended meaning hadn’t been established until the mid-20th century, so the poet couldn’t have been hinting at that. But there was another extended meaning of the word that had been around for centuries by the time the poem was written. Even dating back to the time of Shakespeare, vixen was a derogatory term meaning “an ill-tempered woman.” The poet certainly would have understood this meaning, so this particular choice of name is interesting.

Comet

The Great Comet of 1811 was a memorable marvel that the poet most certainly would have experienced. It was visible to naked eye for 260 days in 1811 — a record that stayed untouched until the Hale-Bopp comet of 1997 visited our solar system. A mysterious body that hurtled through the night sky must have seemed the perfect name for a reindeer that did the same thing.

Comet itself goes back to the Greek kometes “long-haired,” describing the comet’s tail in the night sky. It journeyed from Greek through Latin and Old French before arriving in English sometime before the 12th century.

Cupid

Cupid was the Roman god of erotic love, the son of Venus and Mercury. (Greek mythology gave him the name Eros.) This seems like an odd choice for the name of a reindeer in a Christmas poem that has nothing at all to do with sex or romance. However, Cupid had long be depicted as a winged god, so perhaps it was his ability to fly that the poet had in mind when he named this reindeer.

The Donner Party

This is where it gets a little weird: When the poem was first published, there was no Donner in it. The next reindeer on the list was Dunder, which was, according to Snopes, part of a common Dutch exclamation, “Dunder and Blixem!” — meaning “thunder and lightning.”

Henry Livingston Jr., it should be noted, had a Dutch background, while Clement Clark Moore came from British stock.

Another publisher soon changed Dunder to Donder, perhaps to more closely mimic the common pronunciation. (The Post seems to have rendered it as Dunter when we printed it in 1826. Was this an editorial decision or a printmaker’s error? We may never know.) When Moore added the poem to his collection in 1844, he retained this change to Donder.

Donner (the German word for “thunder”) wouldn’t make an appearance until the turn of the century, and it wouldn’t be cemented in our collective conscience until 1949, when Gene Autry popularized the Johnny Marks song “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

From Blixem to Blitzen

And yes, the last of the reindeer named in the poem was originally called Blixem, the Dutch word for “lightning.” This was changed in pretty short order to Blixen, probably to better rhyme with Vixen. (The Post used Blixen in 1826.) In 1844, when the poem appeared in his collected works, Moore — perhaps knowing more German than Dutch — changed the name to Blitzen, the German word for “lightning.” But if Moore did know German, it is odd that he kept the spelling Donder instead of altering it further to Donner, as we know it today.

Rudolph

Glowing-nosed Rudolph was a latecomer to the herd. Created by Robert May in 1939, the story of Rudolph was created as part of a Montgomery Ward Christmas promotion — a giveaway to children who visited Santa in their stores that year. Rudolph didn’t become a mainstay of Christmas in America until, as I mentioned earlier, Gene Autry recorded and popularized “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1949.

The name Rudolph comes from the Old High German Hrodulf and literally means “fame-wolf” — an odd choice for a character depicted as a handicapped underdog. May wasn’t thinking about etymology, though. The name was chosen primarily for its alliteration; documents show that, as he was working out the story, May scribbled down a number of other possible names — including Rollo, Reginald, and Romeo — before deciding on Rudolph.

Featured image: “Reindeer in the Night Sky” by Manning de V. Lee, Dec 1, 1954. Copyright © SEPS.

When Christmas Pie — and Christmas Itself — Was Banned

When I was a girl, my parents and I spent Christmas Day with my father’s family. And when we moved to another city, we always drove back for the traditional Christmas.

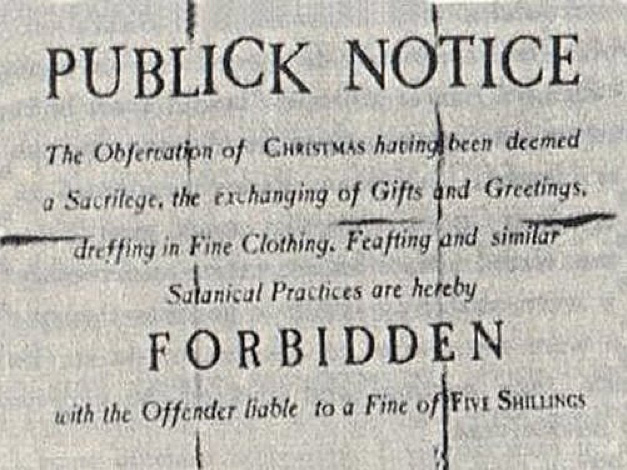

It was the same each year: Turkey and all the trimmings, polished off — somehow I always still had room — with pumpkin pie. But I had no idea how far back some of the traditions went, including the celebration of Christmas itself. It was only later that I chanced upon the fact that Christmas was not only not celebrated in some places, it was banned. Legally. In this country, in New England, and across the Pond in England.

The years in which Christmas was banned, by law or custom, would leave their mark on Christmas and how we celebrate it. Mince pie — also known as Christmas pie — is one example.

Christmas pie was originally a small British fruit-based mincemeat sweet pie traditionally served during the Christmas season. Its ingredients are thought to go back to the 13th century when returning European crusaders brought back Middle Eastern recipes.

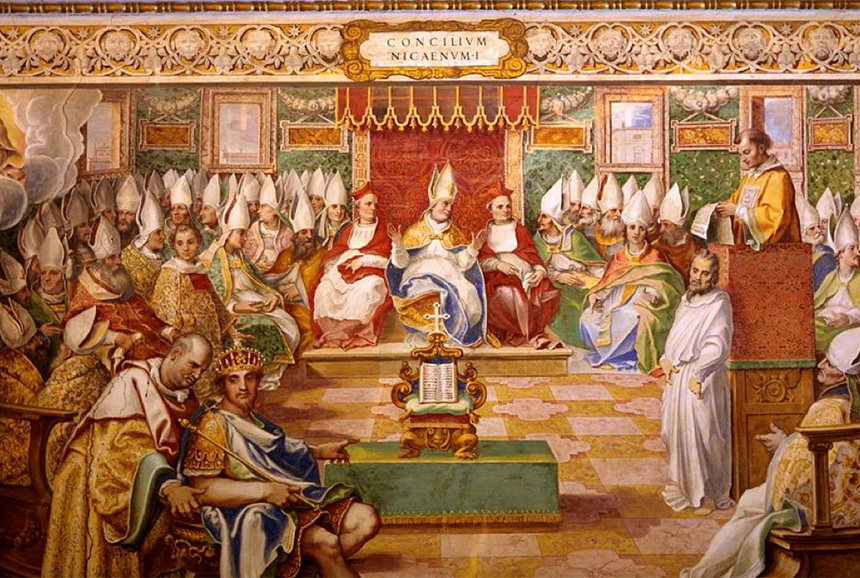

It may go back still further, to the old Roman custom during the Saturnalia of Roman priests in the Vatican being presented with sweetmeats.

When in 325 A.D. the Council of Nicaea set the date for the birth of Jesus as December 25, that, intentionally or not, grafted the new Christmas onto the old Saturnalia, which was the most popular celebration of Roman times. The seven-day festival that started December 17 to honor the god Saturn and welcome the winter solstice gave us today’s tradition of holiday greenery, gift giving, and the office party (or variations thereon), for the Saturnalia was a time of much drinking, some carousing, certainly unrestrained revelry.

Complaints about Christmas, or more specifically the celebration thereof, threaded through the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages, and then came into their own in Tudor England.

Christmas in Merrie Olde England was seen by the Puritans as a bit too merry. The holiday had come to be marked by bear baiting, beer and ale, and other spirits flowing in the taverns on Christmas Eve, rowdy crowds celebrating “the Lord of mis-rule.” Come Christmas morning, minstrel-like parades would march down the aisles in churches where services were being held.

Unable to rein in the excesses, the Puritans threw the baby out with the bathwater. There would be no Christmas. Not just the celebrations and traditions, but Christmas Day itself. It would be just another day.

Their no-Christmas policy crossed the Atlantic with them on the Mayflower. When the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth in December 1620, they observed the Sabbath on Sunday, but, come Christmas Day, went ashore to work.

Back in England, when the Puritans came to power under Cromwell, Christmas was banned by an act of Parliament in 1647. On Christmas Eve, the town crier would move through the streets of London, ringing his bell, proclaiming, “No Christmas! No Christmas!”

And no Christmas meant no Christmas pie.

The small fruit-based sweet pie had grown larger with the years, and by the 17th century it was long and narrow, with a depression in the center for a baby doll representing the baby Jesus in his manger. The Puritans considered this idolatry and would have none of it.

When Parliament lifted the ban on Christmas in 1660 — Cromwell was out and Charles II had ascended the throne — Christmas pie returned, in the circular form we know (and with no doll).

My family did not serve mince pie; we had pumpkin pie in Michigan then. When we moved to New England, I still enjoyed pumpkin pie but discovered they not only had mince pie as an alternate but also squash pie.

That pumpkin pie became a national favorite may go back to the Pilgrims, who, being Puritan, did not celebrate Christmas but had a great plethora of pumpkins. So great it inspired the verse:

We have pumpkins at morning, and pumpkins at noon,

If it was not for pumpkins, we should soon be undoon.

Whichever pie you choose for your celebration — pumpkin or mince or sweet potato or squash — may it bring as much joy as your other Christmas traditions.

Featured image: Saturday Evening Post cover from November 18, 1905, by Guernsey Moore ©SEPS

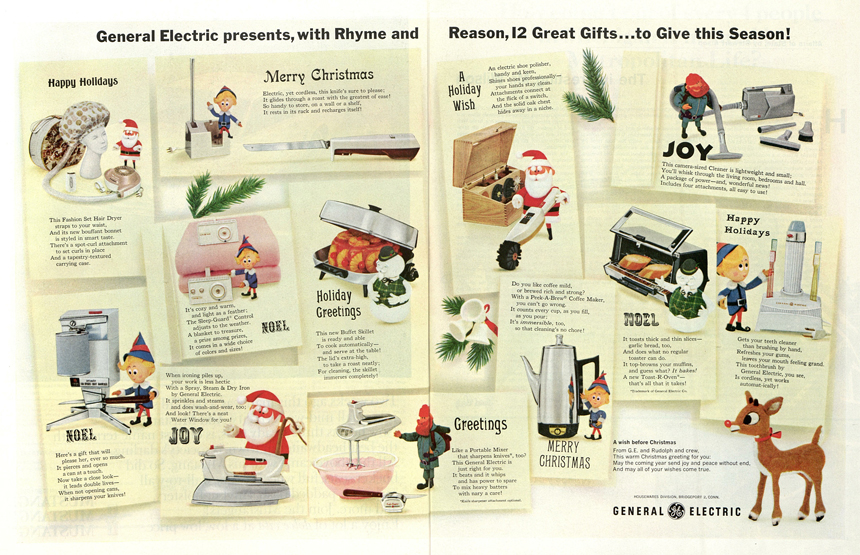

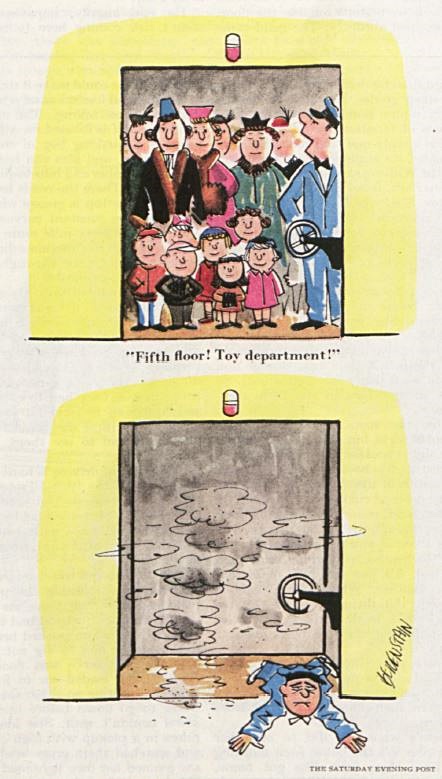

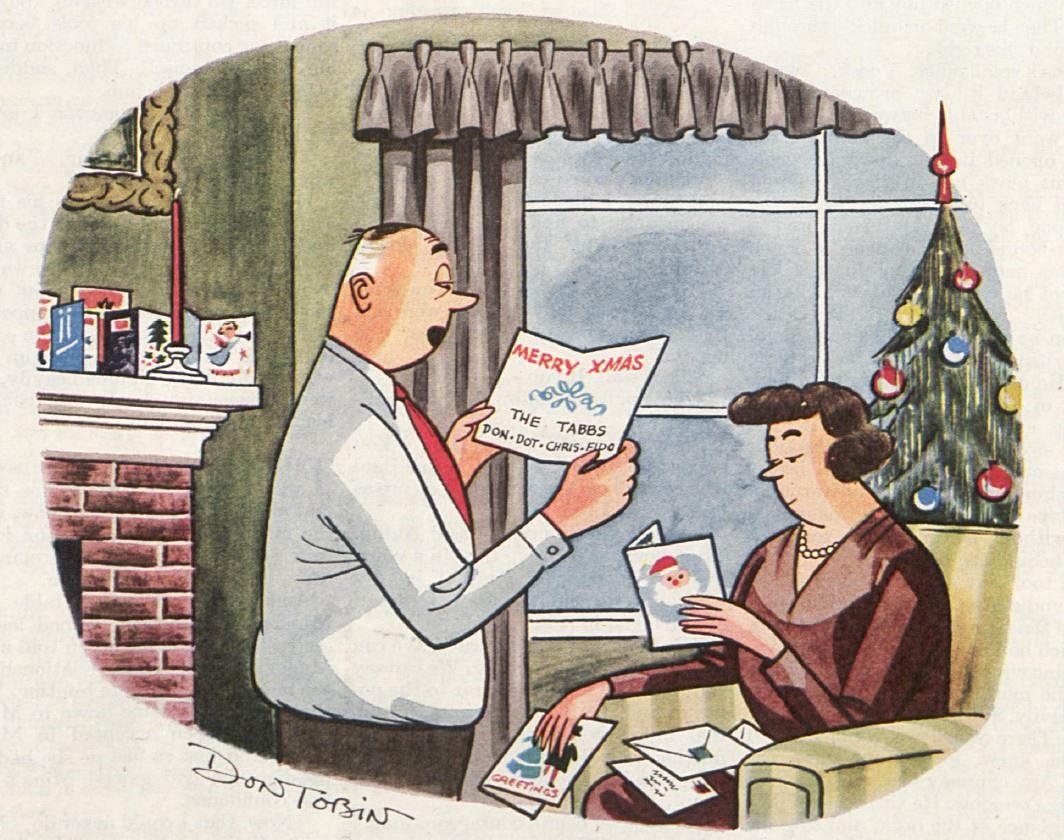

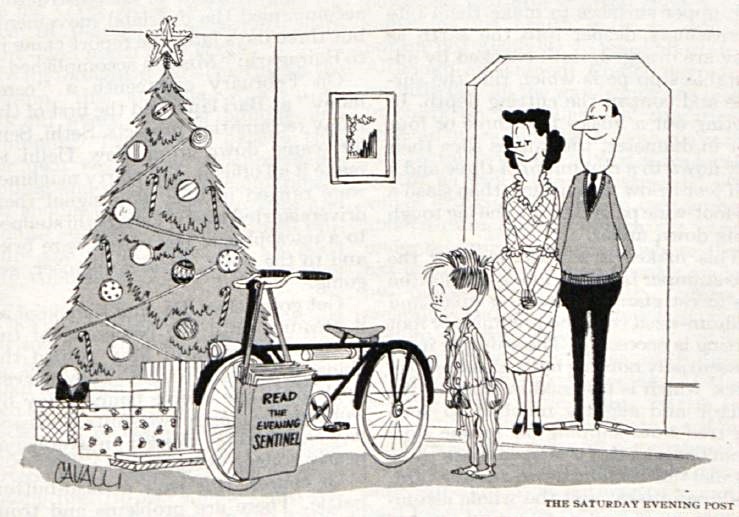

Cartoons: Merry Christmas!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Tom Henderson

December 19, 1959

Walt Wetterberg

November 24, 1951

Lepper

December 22, 1951

Roy Fox

December 20, 1958

December 12, 1959

December 16, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The 8 Scariest Christmas Monsters

From the Christian celebration to elements of Yule and images drawn from advertising art, literature, and more, the idea of Christmas in America comes loaded with its own set of stories and symbols. However, one bit of lore that hasn’t quite made the transition to the States is the existence of an entire class of Christmas monsters. That’s right; to you, it might just mean Santa and elves and reindeer, but in many other countries, Christmastime means Monster Time. Here’s a bestiary of beings that lurk in the silent night.

1. The Krampus

The trailer for Krampus (2015) (Uploaded to YouTube by Legendary)

The Krampus has become the king of the Christmas monsters. He’s broken in America in a big way in the last couple of decades, notably with comics and a handful of horror films. A counterpart to Santa who punishes bad children, Krampus has his roots in the eight Alpine countries (Germany, Austria, Italy, etc.) stretching back to at least the 1500s. Represented as a demonic humanoid with goat horns (recalling the pagan “Horned God”) and cloven feet, Krampus frequently carries chains, bells, and branches (which are used to whip the bad kids). Krampusnacht, December 5, is the night before the Feast of St. Nicholas; this is recognized in a number of European communities with activities like parades. “Krampus Walks,” featuring attendees in costume, are becoming more popular in the U.S.

2. Knecht Ruprecht

Not so much a monster as another thrasher of naughty children, Knecht Ruprecht is a sidekick of Saint Nicholas in German tradition. Varying versions of the story have Ruprecht leaving nuts or treats for good children, while leaving switches (for their parents to beat them with) for the bad. Still other versions cast him as more of a helper than a punisher. He’s usually depicted in dark robes and carrying a bundle of sticks. The similar character of Belsnickel appears in other traditions, and has many traits in common with Ruprecht.

3. La Befana

Sometimes called The Christmas Witch, Befana rises from Italian folklore to give gifts to kids on Epiphany Eve (January 5). Befana is said to fly on a broomstick and leave treats and presents in stockings, while leaving behind sticks or coal for bad children. Interestingly, while the story has been known for some time, the Befana traditions weren’t really subject to widespread practice in Italy until the 20th Century. Frau Perchta is a similar personage that may have been inspired by Norse myths; she fulfills the same function as Befana while alternately appearing as either a beautiful maiden or old woman (although she’s given to sometimes cutting open bad kids and stuffing them with straw).

4. Gryla, The Yule Lads, and The Yule Cat

Iceland brings us one of the more elaborate Christmas monster mythologies, which stem from Yule lore. Grýla is a trollish giantess who lives in a cave with her large (and LARGE) family. There’s Jólakötturinn, the monstrous Yule Cat. There’s her lazy husband, Leppalúdi, who mostly doesn’t leave the cave. And there’s her 13 sons, the Jólasveinar, popularly known as the Yule Lads. On the whole, their reputation rests on their willingness to devour people, including children. Jólakötturinn, specializes in eating people who didn’t get new clothes before Christmas Eve (which ties back to a tradition of people getting new clothes as a reward for being good). Each of the Yule Lads has a particular prank or form of harassment associated with them that they perpetrate on the people, from stealing food to candles. Stories of the family go back centuries, but the 1932 poem Yule Lads by Icelandic poet and politician Jóhannes úr Kötlum set the canon for the names and behaviors of the Lads as they’re perceived today.

5. Père Fouettard

His name means Father Whipper in French, and he comes by it for good reason. Another companion of St. Nick, Fouettard is said to journey with the jolly man on Saint Nicholas Day and dole out beatings to the bad children while Nick rewards the good ones. Usually depicted with sticks and reeds, Fouettard is also described as frequently wearing a wicker basket on his back for the capturing of naughty children. He’s also traditionally shown as bearded, bedraggled, and dirty, as if having soot on this face. Unfortunately, the soot in recent years devolved in the use of blackface by cosplayers and parade-goers, stirring controversy in a manner similar to Zwarte Piet (Black Peter).

6. Zwarte Piet (Black Peter)

Black Peter first appeared in a Dutch book in 1850 and became a popular companion for Sinterklaas (aka Santa). In the book and later writings, the character is a Spanish Moor that becomes Sinterklaas’s assistant, occasionally punishing or even stealing naughty children. While it was quite common to see people don colorful costumes and blackface to depict Peter for many years, recent decades have seen a rise in controversy as various groups and celebrities have spoken against the practice. Some parades and programming have changed the appearance and the style of the character, while others doggedly adhere to what they see as tradition. Some communities and school corporations in Europe have taken to phasing the character out entirely.

7. Hans Trapp

Almanach de Wintzenheim, Wikimedia Commons, GNU Free Documentation License, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Hans von Trotha was a real German knight in the 1400s. His story in folklore has become that of Hans Trapp. Over time, Trapp grew to be depicted as the “Black Knight” that stalked the Wasgau hills, frightening children and appearing in other legends. In the Alsace region (in northern France that borders Germany and Switzerland), Hans Trapp merged with the St. Nicholas story, replacing Knecht Ruprecht as Santa’s punisher.

8. Mari Lwyd

Yes, Virginia; there is a zombie horse of Christmas. This is a specific outgrowth of the wassailing tradition in Wales. In the States, we think of wassailing as simply caroling, but it’s more of a mix of caroling and trick-or-treating; in wassail, groups moves from home to home and sing in exchange for a drink (frequently, wassail itself, which is a hot mulled cider). In the Mari Lwyd tradition, one member of the group hoists a horse’s skull on a pole that is draped with a hood and leads the wassailers about. The Mari Lwyd group would sing and the home dwellers would respond in song; this went back in forth until the Mari Lwyd-bearers got their drink or moved on. The practice fell out of favor in the early 20th century, but experienced a revival before the year 2000. That year, Aberystwyth in Wales put together “The World’s Largest Mair Lwyd” for millennial celebrations.

Featured image: Nicola Simeoni / Shutterstock.com.

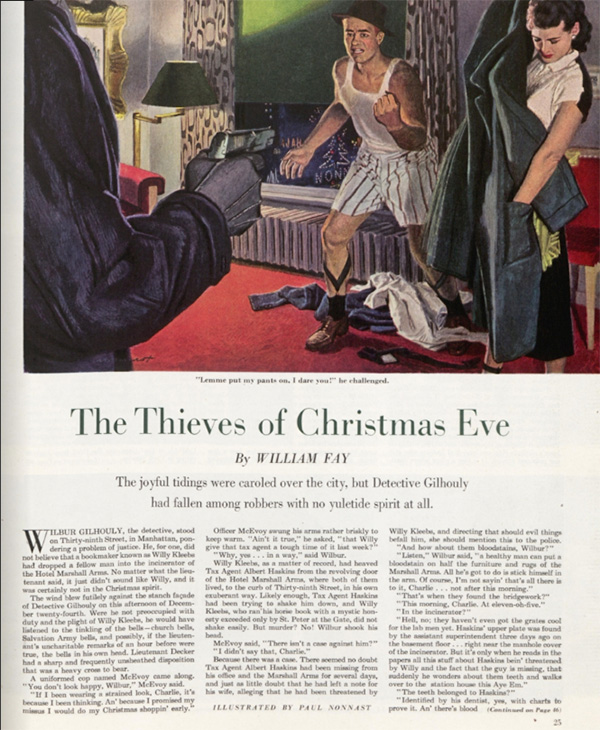

“The Thieves of Christmas Eve” by William Fay

William Fay was a short story writer for the Post in the mid-1900s. His hard-boiled detective stories echo the fashionable trends of noir storytelling. In “The Thieves of Christmas Eve,” detective Wilbur Gilhouly is down on his luck and about to be demoted if he can’t crack a case before Santa is due.

Published on December 24, 1949

Wilbur Gilhouly, the detective, stood on Thirty-ninth Street, in Manhattan, pondering a problem of justice. He, for one, did not believe that a bookmaker known as Willy Kleebs had dropped a fellow man into the incinerator of the Hotel Marshall Arms. No matter what the lieutenant said, it just didn’t sound like Willy, and it was certainly not in the Christmas spirit.

The wind blew futilely against the stanch facade of Detective Gilhouly on this afternoon of December twenty-fourth. Were he not preoccupied with duty and the plight of Willy Kleebs, he would have listened to the tinkling of the bells — church bells, Salvation Army bells, and possibly, if the lieutenant’s uncharitable remarks of an hour before were true, the bells in his own head. Lieutenant Decker had a sharp and frequently unsheathed disposition that was a heavy cross to bear.

A uniformed cop named McEvoy came along. “You don’t look happy, Wilbur,” McEvoy said.

“If I been wearing a strained look, Charlie, it’s because I been thinking. An’ because I promised my missus I would do my Christmas shoppin’ early.”

Officer McEvoy swung his arms rather briskly to keep warm. “Ain’t it true,” he asked, “that Willy give that tax agent a tough time of it last week?”

“Why, yes … in a way,” said Wilbur.

Willy Kleebs, as a matter of record, had heaved Tax Agent Albert Haskins from the revolving door of the Hotel Marshall Arms, where both of them lived, to the curb of Thirty-ninth Street, in his own exuberant way. Likely enough, Tax Agent Haskins had been trying to shake him down, and Willy Kleebs, who ran his horse book with a mystic honesty exceeded only by St. Peter at the Gate, did not shake easily. But murder? No! Wilbur shook his head.

McEvoy said, “There isn’t a case against him?”

“I didn’t say that, Charlie.”

Because there was a case. There seemed no doubt Tax Agent Albert Haskins had been missing from his office and the Marshall Arms for several days, and just as little doubt that he had left a note for his wife, alleging that he had been threatened by Willy Kleebs, and directing that should evil things befall him, she should mention this to the police.

“And how about them bloodstains, Wilbur?”

“Listen,” Wilbur said, “a healthy man can put a bloodstain on half the furniture and rugs of the Marshall Arms. All he’s got to do is stick himself in the arm. Of course, I’m not sayin’ that’s all there is to it, Charlie … not after this morning.”

“That’s when they found the bridgework?”

“This morning, Charlie. At eleven-oh-five.”

“In the incinerator?”

“Hell, no; they haven’t even got the grates cool for the lab men yet. Haskins’ upper plate was found by the assistant superintendent three days ago on the basement floor … right near the manhole cover of the incinerator. But it’s only when he reads in the papers all this stuff about Haskins bein’ threatened by Willy and the fact that the guy is missing, that suddenly he wonders about them teeth and walks over to the station house this Aye Em.”

“The teeth belonged to Haskins?”

“Identified by his dentist, yes, with charts to prove it. An’ there’s blood on the incinerator cover — half washed away, careless like, so that some of it shows up under the glass. Same type as in the apartment, an’ there’s stains in the freight elevator too. It’s the self-service-push-a-button type, you know, and the lieutenant, with his big brain well, naturally, he’s got Willy takin’ the corpse down in the middle of the night — that wouldn’t be too hard — an’ dumpin’ it through the manhole cover. The upper plate? That’s one of them little ironies that murderers have to put up with, the lieutenant says. Mr. Haskins’ upper plate, accordin’ to him, just dropped out unnoticed while Willy was luggin’ the body.”

“Well,” said Officer McEvoy, “I got to shove off, Wilbur. Merry Christmas, if I don’t see ya.”

Wilbur cased the crowd for larceny and lighter mischief with that celebrated eye and memory for faces that had once caused police reporters to refer to him as “Elephant” Gilhouly. Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan, his driver, drove up in the squad car. He was young, unburdened by responsibility, and in possession of a brooch for his girlfriend. It was a lovely item, worth a month’s pay anyhow, and Wilbur reflected, without bitterness, that in his own position, as the loving husband of one and the doting father of four, he had to face the fiscal realities. He had eighty-seven dollars and forty-three cents, and a stern note from a finance company whose kind facilities it had never been his intention to abuse.

“I think maybe I’ll step over to Jablonski’s for a minute,” Wilbur said. “Don’t take any wooden lieutenants; we got one already.”

At Jablonski’s Junior Joyland, Wilbur, on tiptoe, caught the attention of Mr. Jablonski. Mr. Jablonski, who gave a substantial discount to cops and firemen, said, “I got it,” and passed to Wilbur, over people’s heads, $28.74 worth of railroad, in a box — $28.74, that is, with the discount. “What it cost me,” said Mr. Jablonski.

The trains were for little Wilbur, nine. He bought a doll’s house then for his daughter Mavis, a puppet show for Agnes-Mae, and a construction set for Edwin. And then, because — well, because love still beat more strongly in his breast than prudence, he went to a division of Jablonski’s Junior Joyland known as Mommy’s Mart, and made a twenty-two-dollar down payment on a portable, kitchen-size washing machine for Myrtle, his wife, and the one true love of his life. He would call back for the washing machine, he explained to Mr. Jablonski; the other packages he’d take.

“This is a general clearance or you would not of got such bargains,” said Mr. Jablonski. “We will be open till midnight. Come in again; tell your friends.”

Wilbur, with his packages chin-high, moved bravely toward the sidewalk. Jablonski’s, he noted, though a humble establishment, was graced by a better upholstered and more firmly bearded St. Nicholas than most. Wilbur found this somehow reassuring, though his vision was limited. He walked into a mailbox and his packages tumbled. He bent to retrieve them. He heard a mirthless and familiar voice.

“Santa’s li’l’ helper?” someone said.

Well, that was Lieutenant Decker for you. Always the sarcasm, be it Christmas or doomsday.

“What’s your explanation, Gilhouly?”

Wilbur tried to smile. He indicated the packages. “I’m just mindin’ these things for some friends, lieutenant.”

“What friends?”

“Well, my kids,” Wilbur said, then met the other’s cold gaze more steadily. “My kids are my friends,” he said with pride. The truth, after all, was a matter precious to Wilbur.

“You’re a wise guy, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He placed his packages in the squad car.

“Well, Gilhouly,” Lieutenant Decker said. “against my better judgment they set bail for Willy Kleebs. You an’ that judge down at Special Sessions should have your skulls scraped.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You an’ Kleebs was always pretty chummy, Gilhouly. How well did you know him?”

“I’ve known him both in line of duty,” said Wilbur truthfully, “and after hours. I locked him up four times for makin’ book, and he is Agnes-Mae’s godfather. Look, lieutenant, have you checked the guy’s wife?”

“I personally put through the check on the widow, Gilhouly. A fine-type woman. Unimpeachable. A Vassar girl. We had a nice talk about some cultural matters … Take that silly grin off your puss!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Here are your orders, then. Kleebs right now is next door in the Marshall Arms Barbershop for a several-times-over. I want you to watch every place he goes, with regular reports to me. You an’ Kaplan, don’t let him out of your sight! That clear, Gilhouly?”

The lieutenant strode indignantly away. Wilbur and Kaplan moved over to the barbershop window. Willy Kleebs appeared to be taking the full six-dollar treatment in the No. 1 chair. He waved gaily to Wilbur and Kaplan.

“He never dropped nobody into no oven,” Wilbur said.

“Howja do at Jablonski’s, Wilbur?” Kaplan asked. “Any good?”

“Take a look for yourself. There’s nothin’ like havin’ a family, my boy. Take a look in the back of the car.”

In the No. 1 chair, Willy Kleebs wore a look of deep content. Good old Willy, always smiling — good times, bad times, always the same old Willy. Kaplan called to Wilbur from the curb.

“You put them in the back of the car? What car?”

“Right there. In the back.” He walked over to the car, looked in. The back of the car was empty.

“They ain’t here,” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said.

Wilbur smiled weakly. It was a joke. I’m laughing, Wilbur thought. But the brutal truth prevailed.

“Gone,” said Kaplan. “Like I toldja.”

“Eighty-one dollars,” Wilbur said. His senses reeled. Jablonski’s Santa Claus kept ringing his bell and chewing his gum. Wilbur, a tall man, turned dismayed eyes on the multitude. He saw no one sprinting through traffic with a doll’s house and assorted lumps of joy. He wanted to cry. This was Gilhouly, the good provider, with six dollars and some cents remaining, and a week late with the finance company. This was Gilhouly, the —

“Wil-bur-r-r!” Kaplan called from the plate-glass window of the barbershop. Wilbur walked over. “Look,” said Kaplan.

The No. 1 barber chair was empty. Willy Kleebs was gone.

…

It was not easy in the station house to stand before your fellow officers while Lieutenant Decker peeled your dignity away — artfully and easily, like the skin of a scalded peach.

“I always knew you were a whale of a fellow, Gilhouly,” the lieutenant said. “I could tell it by the blubber in your head.”

Less loyal comrades snickered; others looked away. The lieutenant was in the process of enjoying himself.

“I would say, Gilhouly, that it’s gonna be strictly brass buttons an’ blue coat from here in. Staten Island, maybe, or the Bronx frontier, where we can push you inta Yonkers.”

Wilbur dropped his eyes. You took it, that was all. He could remember the last time he’d been threatened with a return to uniform. His wife had stemmed her tears. “Wilbur,” she had said with priceless loyalty, “you look beautiful in blue.”

Early-winter’s darkness was over the town as Wilbur left the station house with Kaplan. Lights were everywhere, though it was only five o’clock. They came to where the squad car still stood parked before Jablonski’s.

Wilbur was watching Jablonski’s Santa Claus, whose face he had not had a chance to view at leisure until now. He stepped closer, examining minutely, and with small attempt at politeness, Santa’s rosy cheeks. Into operation came the old Gilhouly intuition. Wilbur moved and Santa jumped. Wilbur caught old Santa by the beard.

“Legomme!” Santa shouted.

But Wilbur clung tenaciously. He pulled the beard the length of the elastic, then let it snap.

Old Santa howled. “Legomme! Cudditout!”

It was not really Santa. It was a man named Mutuel Minskoff, who worked for Willy Kleebs. “What I thought,” said Wilbur.

Mutuel Minskoff was a bookmaker’s runner, which is no kind of Santa Claus at all, but one who takes bets on horses. Wilbur shook Jablonski’s Santa Claus.

“Where’s Willy Kleebs?” he demanded. “Where’s them packages you stole out of the car?”

“Honest, Wilbur — honesta me mother’s grave, I don’t know what you’re sayin’!”

Wilbur, with Kaplan’s assistance, pushed Mutuel Minskoff into the car. Wilbur stretched the beard’s elastic its full, intimidating length. “You gonna tell me?”

“We have little or nothing to say to one another,” Mutuel said with dignity, “except that I don’t like your attitude.”

Wilbur let the beard snap. He was not a man disposed toward cruel means of persuasion, but he was nonetheless determined.

“Let’s get it straight, Minskoff,” Wilbur said. “A fifty-dollar-per-diem wise guy like yourself don’t become a ten-dollar St. Nicholas because he likes to get stuck in chimneys. Well, do you?”

“This is our slack season, Wilbur.”

“Never mind that. Where is Willy Kleebs?”

“He went to visit his ninety-three-year-old mother in the Bronx.”

“Where’bouts in the Bronx?”

“That’s one of those things Willy has always kept to himself,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “an’ the little old lady don’t know he’s in trouble with the cops, you understand? In fact, she thinks that Willy’s in the feed-an’-grain trade.”

“You’re lyin’, Minskoff,” Wilbur said, but he did not really believe the man was lying. It sounded like Willy, all right. He restrained Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan from snapping the beard again. “I’m asking you, Mutuel, Number One — who stole my packages? I am asking you, Number Two — why you been standing all day in front of Jablonski’s making like an elk driver?”

“As for the packages, Wilbur, believe me, I dunno. As for Point Number Two, I’ve been watchin’ for Tax Agent Haskins. Willy didn’t kill ’im. I been waitin’ here for Haskins because we know he’s got to come back.”

“Come back for what?”

“Haskins made one mistake, Wilbur. Just like he dropped his upper plate next to the incinerator on purpose, he also drops somethin’ else in Willy’s suite, but not on purpose.”

“What did he drop?”

“He dropped his safe-deposit-box keys, Wilbur. A whole ring o’ them, he dropped. You get it? Haskins is a crook. An’ where does a crook with a big wad o’ dough an’ a small pay check hide this embarrassin’ disparity of means? In safe-deposit boxes, don’t he? In eight different banks, under eight different names.”

“You know this? You’re not lyin’ to me, Minskoff?”

“Here,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “are the keys. Understand, they’ve just got numbers on them an’ we don’t know what banks, an’ we don’t know what names this guy is usin’. All we know is he has got to get them keys.”

“Why didn’t Willy come to the police with these?”

“Willy sees that with Decker on the case, an’ blabbin’ like he does, there might be talk in the papers the cops have got a certain set of keys, an’ this Haskins will just take off like a bluebird. Willy would like to catch Haskins himself. Willy is an honest man what pays his taxes, but this guy not only tries to shake ‘im down, he owes ’im maybe twenty grand on horse bets.”

“Tell more, Mutuel. Tell all.”

“Well, Wilbur, we figured that Haskins, the crook, wanted to lam for liberty before the tax department caught on to the size of his personal assets. So what’s a better way to get off with a bundle o’ dough an’ not be tailed than to have yourself declared murdered? That’s why he sets up this frame about Willy, an’ why your friend, the lieutenant, begins to drool about maybe he can have Willy measured for that warm chair up in Ossining. You get it?”

“It happens also to have been my personal theory,” said Wilbur modestly. “Except, of course, I never knew about the keys. You better hand ’em over to me like a good boy, Mutuel. Thass right. Now get back on the job; keep ringin’ that bell … And, Kaplan,” he said, “you keep an eye on Santa.”

This was Gilhouly, the hound of justice, on the scent. The Hotel Marshall Arms, set in the shopping district of New York, was vast, commercial, and of wholesome reputation. In the plaza, as he entered, Wilbur rejoiced at the Christmas tree that rose gigantically for several floors — its glowing lights bespeaking warmth and good cheer in a cold and unbelieving world. Willy Kleebs’ suite, where Wilbur thought a little look around might help, was on the seventh floor.

“Where’s the cop they had watchin’ this suite?” he asked the bellhop who let him in by means of a key.

“The lieutenant said there was no pernt to it,” the bellhop reported. “The lieutenant sent ’im after bundle snatchers.” The bellhop, with a taste for police procedure, hovered.

“Blow,” said Wilbur. “Get lost, sonny.”

Wilbur closed the door behind him and was immediately aware of another’s presence. A woman wearing an apron and a somewhat guilty look was dusting, or at least appeared to be dusting, in the sitting room. “This place is under surveillance,” Wilbur said. “Who are you?”

“Why, Mr. Kleebs always lets me have a key to do the cleaning,” the lady said. Her apron was ruffled and unspotted. She had a way of placing hands on hips that bespoke some gayer setting and invoked old memories of action that had nothing to do with dustpans. She looked more like a cupcake to Wilbur than she looked like somebody’s mother rubbing honest knuckles raw. “If you’ll excuse me — ”

“One minute,” Wilbur said. The files of his memory were opening. “Hold on, lady.” He could smell clams, somehow. Why clams? Coney Island? No, it wasn’t Coney Island. Brighton Beach? Not Brighton either. Then it snapped. It came to him. “Hello, Kitty,” Wilbur said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Gypsy Kitty Klein, from Rockaway Park. Used to tell fortunes for a thief named Hennessey. Must be fifteen years since I locked ’im up. You lookin’ for something, Kitty?”

“Officer,” said Gypsy Kitty, “you are playing the wrong trombone. Now, if you don’t mind — ”

“Lookin’ for some safe-deposit-box keys, Kitty?” Wilbur was swinging in the dark, but batting rather well. The proper button had been pressed. “You couldn’t by any chance be Mrs. Albert Haskins, could you? The Vassar girl? The little widow who had the nice cultural chat with the lieutenant?”

“As a matter of fact, I was really only — ”

“Don’t apologize, an’ don’t get excited, Kitty, because — well, about those keys; Homicide ain’t even heard o’ them. Me, Gilhouly; I got the keys, an — ”

“Don’t move, Gilhouly! Stay where you are!” The voice was authoritative. Wilbur did not move. Albert Haskins, with a .38 revolver, spoke distinctly, even minus his upper plate. Wilbur did not move, because his own gun lay deep in the cold-weather bunting he had neglected to unbutton. “Hands higher, Gilhouly … Frisk him, Katherine,” said Haskins to the cupcake.

Mrs. Haskins unbuttoned Wilbur’s winter ulster and rapidly divested him of firearms. She went through his jacket and its inner pockets, searching for the safe-deposit keys, without first having cased the crumpled overcoat that lay on the floor.

“Take off your jacket,” Haskins ordered. “Now your shirt.” Haskins waved his revolver convincingly. “Your pants, Gilhouly!” he commanded.

Wilbur, standing in his underwear, said, “This has gone far enough!” He said this just as Mrs. Haskins, retrieving his coat from the floor, shook it lightly once or twice and heard the jingle of keys. This was defeat, abject and full.

“Look out in the hall,” Haskins said to his synthetic widow. Gypsy Kitty gaped out, then motioned all was clear. Albert Haskins put the cool hard metal of his .38 against the warm hard head of Detective Gilhouly and escorted him uncompromisingly along the empty corridor, while Mrs. Haskins flipped a key in the lock of a door marked PORTER. Wilbur, about to spring into desperate action, went quietly to slumberland as something crashed against his head.

I am dead, thought Wilbur; dead in the chill grave. He heard somebody groaning next to him. I am here, he corrected himself, in the porter’s room, and in my underwear, but I am not alone. He rose unsteadily and stood in heavy darkness that was not illumined by the flashes that kept going off in his skull. He found a switch and snapped it on. At his feet lay Mutuel Minskoff in his Santa Claus suit, beard and all. Wilbur tried the door, but it would not yield. He looked about for some suitable means to persuade it. He looked, as well, at Santa.

In the street, by now, Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan was confused. Bitterly he reflected you could trust nobody — not even Santa Claus or your esteemed good friend, Gilhouly. That Minskoff, in particular, had shattered solemn trust, the dog, but here Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan paused. It seemed to him that he saw Minskoff now race wildly through the plaza of the Hotel Marshall Arms, arms waving, shouting.

“The hell ya do!” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said. He interfered with Santa’s headlong haste. He teed off with his strong right arm and pulled off Old Santa’s beard. Old Santa tripped and looked up from the pavement, short of cheer.

“That’s a nice thing to do,” said Wilbur Gilhouly. “A nice way, Kaplan, I must say, to implement the law.”

The lieutenant postulated. He asked, of all who were there to listen, the one seemingly relevant question: “How crazy can you get?” And, Wilbur, beardless, but in his red-and-ermine suit, seemed a fairly apt reply.

“Albert Haskins is alive,” Wilbur repeated. He had stated this without compromise at least one hundred times. “I seen him. He hit me in back of the head. He locked me in a room. Him an’ his wife. She used to be known as Gypsy Kitty Kl — ”

“My dear Gilhouly,” the lieutenant interrupted, “did you see all these interesting things before or after you got slugged in the head? Did Kaplan see Haskins? … Did you, Kaplan?”

“No, sir,” Kaplan was obliged to say, but he was sorry for Wilbur. “All I seen was this Mutuel Minskoff.”

“And where is Minskoff?”

“Like I said before,” said Wilbur, “he was with me in the porter’s room. I had no clothes on and — All right laugh; laugh, all of you! So I had no clothes on, an’ I had to get out of there. I don’t know what happened to Mutuel after that. I took his suit an’ I — ”

“Gilhouly!” the lieutenant said with sudden fierceness. “How much in cash did Minskoff and Willy Kleebs pay you to concoct this story?”

Wilbur leaped to his feet in anger. His doubled fists and squared jaw made Lieutenant Decker blanch. Inspector Gerhardt, until now quietly sitting by, at this point intervened.

“That will be enough for now, lieutenant,” the inspector said. “I happen to know Gilhouly’s record.” A kindly man, he walked over and examined the back of Wilbur’s head. “A severe blow of this kind can induce all kinds of impressions in a man’s mind,” the inspector said. “Don’t try to think now, Gilhouly. After all, we just now combed the hotel with a flock of cops. We’ve got men in the lobby and at the rear and side exits. The trouble is, Gilhouly, that your story’s not standing up. There’s no sign of Haskins, if he’s alive, and there is no sign of Minskoff. There is nothing in our available files — well, tonight, at least — to support what you say about Mrs. Haskins’ past record. Are you suffering from any personal troubles, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He glanced at the clock. He shrugged. He smiled resignedly. “Three hours to Christmas, an’ I’m supposed to be home by now … You mind if I phone my wife?” he asked. “It’s only a nickel call.

“ … Merry Christmas, darling!” Myrtle said. “Whatever’s been keeping you? … You’re what, dear?”

“All loused up,” said Wilbur. “I thought I oughta tell you I am strictly a crushed cornucopia, baby … Somebody swiped the packages … You what? You ain’t sore? … An’ I can’t get away just now; it seems — ”

“I will be right down,” Mrs. Gilhouly said. “I will be right down in a half hour, Wilbur, to meet you. Don’t you worry … The children? Well, your sister Marge is here.”

Wilbur and Kaplan sat alone in the room. Time passed. There would be further questioning, the inspector had said, when he was able to piece all the claims and counterclaims together, but there did not seem much sense in keeping eight men at the Marshall Arms much longer in pursuit of the unestablished ashes or person of Albert Haskins. Not tonight, of all nights. There was, to be sure, an emergency call from the Hotel Marshall Arms, but it did not concern the detective bureau. The lights of the giant Christmas tree had been shorted; there had been sparks. There was always the hazard of fire.

Wilbur walked to the window and looked up at the star. “Kappy,” he said, “do you believe in miracles?”

“Yes,” said Kaplan; “from now on, anyhow. Turn around, Wilbur. Turn around slowly.”

Wilbur turned. He saw. framed in the wide door of the room, Tax Agent Albert Haskins. Mr. Haskins was in the safekeeping of the emergency squad. Inspector Gerhardt stood with them.

“This,” said the inspector, “is what shorted the circuit on the Christmas tree. It seems he jumped into it from a third-floor window when all those cops were arriving to check on Wilbur’s story. His idea was to cover himself with decorations, then climb down later, I guess, but it got cold up there and he must have been stamping his feet. Anyhow, he blew the lights and put a nice shock into himself. It wasn’t till the lights came on again that the boys could see him hangin’ there like a peppermint stick. We thought maybe you would like to drop him in the lieutenant’s stocking, Gilhouly.”

Wilbur approached Tax Agent Haskins without malice. He touched the lump behind his ear, and then touched Mr. Haskins, to be sure that he was real. He wasn’t even mad at the lieutenant.

“As for small details,” the inspector said a little later, “we can attend to them in due time. We’re picking up Mrs. Haskins and a porter who was in cahoots with them. You were right, Gilhouly, from the beginning, but the way I figure it, tonight a family man’s got things to do.”

It was a clear night. It was cold and framed in beauty. There were lights in the sky and in the Marshall Arms Hotel and in Jablonski’s Junior Joyland. Mr. Jablonski himself stood on the curb with Willy Kleebs.

“Merry Christmas,” said Willy, “to you and yours, Wilbur, from me an’ my ol’ lady … Good evenin’, Mrs. Gilhouly.

Out of the shadows now, wearing a borrowed overcoat above a porter’s uniform that fitted him like a green banana; Mutuel Minskoff emerged.

“I never deserted ya, Wilbur,” Mutuel said. “Willy came back and I told him you were in trouble, an’ when we got here, there’s this Haskins, like a two-legged mistletoe, hangin’ from the tree. We forgot to kiss ’im.”

“Excuse me,” said Mr. Jablonski, “but if you will kindly look in the car, Mr. Gilhouly. A doll’s house, a puppet show, a construction set and electric trains yet. And on the side of the car, Mrs. Gilhouly, tied like a moose, a washing machine … except it is the full-size model, not the portable, mind you.”

Wilbur stammered. Wilbur tried to protest. “Look, boys, it’s sweet, but I can’t be bribed. You must understand it.”

“At Jablonski’s Joyland,” said Mr. Jablonski, “it’s a general clearance, and besides, I just got paid by a certain party. And what is more, Gilhouly, the inspector knows about it. He says you should kindly shaddup your face while Kaplan drives you home.”

The bells in the church were tolling as Kaplan started the car. They tolled the rich, good message of two thousand years, and Wilbur’s heart was full. Mrs. Gilhouly, a bit snug in the front seat with Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan and her husband, reached for Wilbur’s hand. “I wonder where,” she said, “at this hour, dear, we could find you another beard.”

Featured image: Illustration by Paul Nonnast (©SEPS)

Ask the Manners Guy: Family Food Fight

We have a huge traditional holiday get-together, and my mother, who passed away this year, always made (everyone’s favorite) apple pie. My sister and I both want to make the pie this year as a tribute to the longtime matriarch of the family, but we can’t agree on who will do the honors. It’s getting bitter, verging on nasty. Help!

—Casey Chalmers, Toluca Lake, California

The stress of such a great loss can bring family conflicts to a head, especially around the holidays. But you don’t want to let sibling tensions spoil such an important family gathering. Do the right thing and relinquish the pie-making duties to your sister. Focus on another tradition you can start all your own. Can you knit stockings for new members of the family? Bake a different classic dessert? And how about preparing a loving toast as your own tribute to your mother? Remember, it’s not about the pies, but rather about the stability she gave to the clan. That’s a responsibility you can easily share with your sister if you lead the way.

The Manners Guy is a former bartender who knows his way around awkward social situations. Send your questions to [email protected].

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: (Lewis Tse Pui Lung /Shutterstock.com)

The OTHER Classic Christmas Movies

You know It’s a Wonderful Life and Miracle on 34th Street; you know A Christmas Story and Meet Me in St. Louis.” There’s certainly an authentic canon of Christmas and holiday films in the American library of classics. However, in recent years, other films that take place at Christmas has become something of an ongoing cocktail party discussion. Here are 10 Other Christmas Classics.

10. The French Connection (1971)

The trailer for The French Connection. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Your first thoughts of The French Connection are probably “that car chase” or the boatload of awards it won (which included Oscars for Best Picture, Director, Actor for Gene Hackman, Editing, and Adapted Screenplay). But if you recall the opening, it features Hackman’s Popeye Doyle getting involved in a police action while wearing a seasonally appropriate stakeout disguise: a Santa Claus suit.

9. Edward Scissorhands (1990)

The trailer for Edward Scissorhands. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

The first of eight (and counting) collaborations between director Tim Burton and actor Johnny Depp, Edward Scissorhands is another of Burton’s dark outsider fables. The titular Edward was built by an elderly inventor (Vincent Price, in his final role) who gave him his special hands for utilitarian purposes; unfortunately, the old man dies before he can give Edward regular hands. Discovered by Peg Boggs (Dianne Wiest), he’s brought to live in the Boggs home where he falls in love with their daughter, Kim (Winona Ryder). Much of the movie is a satire of suburbia and conformity, but things that a turn for the Gothic during a fateful Christmas season. The amalgam of tragic circumstances, the Frankenstein-esque reaction of the neighborhood, and Burton’s visuals tie this off as a dark parable that’s inextricably bound to the holiday.

8. Better Off Dead (1985)

The trailer for Better Off Dead. (Uploaded to YouTube by HD Retro Trailers)

This one belongs in the class of “Movies That Probably Wouldn’t Get Made Today.” It certainly has a controversial premise; after aspiring skier Lane Myer (John Cusack) is dumped by his girlfriend for the captain of the ski team, he makes numerous attempts to kill himself before realizing that there’s more to life than his ex. Of course, the approach of the movie is so off-the-wall and Lane’s “attempts” so patently absurd that it stays deeply in the comedy pocket, even with an incredibly serious issue underneath. One of the comic highlights is the extended, and painful, Christmas celebration at the Meyer home wherein Lane’s mom (Kim Darby) sports a bizarre reindeer suit and passes out gifts like frozen dinners.

7. The Harry Potter Series (2001-2011)

The trailer for Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

You might be taken aback by two things here, but yes, it HAS been eight years since the last of the original series, and yes, it fits the parameters. Why? With the exception of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2, which takes place in the latter half of what would have been Harry’s seventh school year at Hogwart’s, each film (like the novels) devotes a not-insignificant section of time to Christmas. The fact that Harry gets any presents at all is a big deal in the first movie, and we later see him spending time with the Weasleys over the holidays as well. The series uses Christmas as a focal point to drive home the idea that Harry has managed to assemble a “found family” and an extensive band of allies.

6. Trading Places (1983)

The trailer for Trading Places. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Who can forget the sight of a drunken Dan Aykroyd in his filthy Santa suit? SNL alum Aykroyd and then-cast member Eddie Murphy powered this socially-aware comedy to box office gold in 1983. And while the plot turns mostly on scheming in the commodities trades and the disruptions caused by Murphy and Aykroyd’s life exchanges, the holiday piece plays a part, particularly in Louis’s (Aykroyd’s) spiral into depression.

5. Gremlins (1984)

The trailer for Gremlins. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

One in a class of horror films that’s inextricably linked to Christmas, but doesn’t abjectly state it (as opposed to the various versions of Black Christmas or the inexplicably-became-a-franchise Silent Night, Deadly Night movies), Gremlins turns on the notion of a bumbling inventor dad getting a last-minute gift for his adult son that turns out to be the adorable Mogwai named Gizmo. Of course, rules are broken and Gremlins are created to the backdrop of well-used holiday tunes and settings, including a Christmas tree ambush. The story could certainly be set at another time of year, but it would lack the resonance of things like the playing of “Do You Hear What I Hear?” leading up to the immortal kitchen battle.

4. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

The trailer for Eyes Wide Shut. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Stanley Kubrick’s final film, a rumination on faith, faithlessness, and the secrets that couples keep from one another, is set against the backdrop of Christmas. The yuletide trappings add despondence to the whole affair, but also provide the elements for a somewhat hopeful final scene. Most of the press for the film centered on the fact that it was a sort of erotic thriller starring the then-married Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, but it’s more of a psychological experiment; in fact, the story was based on the Austrian book Traumnovelle, which literally means “Dream Story.”

3. Iron Man 3 (2013)

Trailer for Iron Man 3. (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

Much like Tim Burton, writer/director Shane Black loves the holidays. Like, really, REALLY loves the holidays. He’s made Christmas central to Lethal Weapon, Edge, The Long Kiss Goodnight, and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, and he does so in Iron Man 3 as well. Black’s film is, in part, an extended commentary on PTSD; Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) is suffering in the aftermath of the Battle of New York from Avengers, and, like many sad feelings, the holiday only seems to make it worse. Along the way, Christmas music and decorations play ongoing roles, and Stark finds himself in snowy Tennessee for chunk of the film. Thematically, we also see how Stark’s constant attempts at overcompensating (his obsession with upgrading his armors, the giant plush he gets Pepper) highlight his own blind spots at dealing with his issues. He does get in a lovely gift note near the end of the film, when Stark leaves young tech fan Harley Kenner (Ty Simpkins) a roomful of gadgets and gear.

2. Batman Returns (1992)

(Uploaded to YouTube by DC)

The first three Batman films of the Tim Burton/Joel Schumacher era all involved some kind of celebration; Batman had the Gotham Centennial and Batman Forever had Halloween, but Batman Returns claims Christmas. Anyone who’s paid attention to Burton’s work knows that he’s returned more than once to the melancholy notes of the season (which we’ll get to a bit later), but that is well and truly layered throughout this film. Part of the emphasis on winter in Gotham is due to the role of the Penguin, but other themes, like the sexism that surrounds the life of Selina Kyle/Catwoman, work into the narrative; Burton manages to combine them in the final conversation between Alfred and Bruce Wayne. When Alfred wishes the hero a Merry Christmas, Wayne, pondering the events of the film, replies, “Merry Christmas, Alfred. Good will toward men . . . and women.”

1. Die Hard (1988)

The original trailer for Die Hard. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers.)

Die Hard is, was, and always will be the standard-bearer for non-Christmas Christmas movies. Ostensibly, it’s an action film, with New York cop John McClane (Bruce Willis) trying to save his wife and her fellow hostages from a band of well-armed thieves led by Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) in Nakatomi Tower (really Fox Plaza) in L.A. From the music over the opening and closing of the film, from the fact that the action centers around a Christmas Eve party, and for dozens of other tiny reasons, this is most certainly a Christmas movie. The final line of dialogue even emphasizes the fact, with Argyle the limo driver speculating on what a McClane New Year’s celebration must be like. And how can you forget one of the most iconic “bad guy kills” in movies: “Now I have a machine gun, too. Ho Ho Ho.”

Featured image: (20th Century Fox; Atlaspix / Alamy Stock Photo)

Cover Collection: Norman Rockwell’s Charles Dickens Series

It was customary for George Horace Lorimer, the legendary Post editor who oversaw the publication from 1899 to 1936, to choose only three sketches or paintings at a time for a cover. But that changed in 1920, when Norman Rockwell met with Lorimer and displayed a multitude of holiday sketches—not just for the coming year but for the entire decade.

It was a risky move, but Rockwell had an ace up his sleeve. The subject matter centered on a common theme, the stories of Charles Dickens, and Rockwell happened to know his boss was

a huge Dickens fan. Lorimer gave the entire series a green light.

December 3, 1921

The first picture for his Dickens series was this illustration of a jocular man wearing a 19th-century hat and holding a cane. When the work was done, the artist confessed to Lorimer that he had dedicated the painting to him. Touched by the gesture, but not one to display sentimentality, Lorimer thanked the young artist with a handshake.

December 8, 1923

Dickens’ portrayal of Victorian society in London captivated Rockwell. He especially admired the street-corner musicians, talented ragamuffins who depended on the kindness of strangers. Rockwell selected his three models for their outward appearance and not their musical talent. Neither “Pop” Fredericks, Dave Campion , nor Bill Sundermeyer could sing or play a lick!

December 8, 1928