In a Word: Mitigation Softens Up Hard Times

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

As thousands suffer from COVID-19 and the rest of us hunker down in our homes (or should), we’re all looking for ways to mitigate something: symptoms, anxiety, fear, sadness. Put another way, we’re hoping to “soften up” hard times — and mitigate is the exact right word to use here.

Mitigate — “to make less harsh, severe, or painful” — stems from Latin mitis “soft or gentle” and agere “to do.” From these roots came the Latin verb mitigare, literally “to soften, mellow, or ripen” but used figuratively to mean “to pacify or soothe.”

Mitigate is a transitive verb, which means it requires an object upon which to act. For example, in Aspirin mitigates a headache, “a headache” is the required object. Put another way, a transitive verb like mitigate does not require a preposition to help it along. But sometimes writers want to slip the word against in there: Aspirin mitigates against a headache is a word too long. Just remember that mitigate is synonymous with alleviate and craft accordingly.

But sometimes that extra against is a sign that mitigate is the wrong verb. Scores of lists of commonly confused words point out that mitigate is often confused with militate — “to exert a strong influence or effect” — especially when against is used with it. A correct example: Three nonprofits came together to militate against loosening the standards.

Frankly though, militate can sound rather formal and highfalutin’. Any sentence that uses it could probably be made clearer by substituting a more common and recognizable verb. Which means whenever you see either mitigate against or militate against, you should consider a little editing.

One final usage tip: If something can be mitigated, it is mitigable, not mitigatable.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: How Long Is a Quarantine?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

It’s never a good time when the word quarantine starts to appear regularly in the daily news. In attempts to stymie the spread of the coronavirus, some quarantines have been put in place to contain people who have been exposed to the virus. But how long should a quarantine last? The coronavirus is believed to have an incubation period of 14 days, so 14 days without showing symptoms of infection has seemed a good guideline for quarantine length so far.

But there’s a specific length of time embedded in the word quarantine itself.

As far back as the fourteenth century, ships coming to Venetian ports from countries thought to be stricken by plague were ordered to remain off the coast for quarantina giorni — literally “a space of forty days” — from the Latin quadriginta “forty.” Most who contracted the bubonic plague would have been killed by it within a week, but the extra time made sure there were no latent cases still aboard.

In French, this concept was called quarantaine, which was altered in English to quarantine, referring to any stretch of forced isolation for medical reasons, by the mid-1600s. But even before then, English law had the concept of a widow’s quarantine, referring to the time — again, often 40 days — that a recent widow was allowed to live on her dead husband’s estate rent-free. After that, the estate would be seized and distributed according to the law of the time.

These days, medical quarantines can last for any length of time, regardless of the word’s etymology. And the recognition of women’s sovereignty has made the widow’s quarantine more or less obsolete.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Bissextus: A Short History of Leap Years

Normally, I devote this column to exploring surprising roots of common words, but today my focus is on a word so uncommon that we only use it every four years. The word is bissextus, and it brings with it a lesson on the history of Roman calendars.

From near the founding of Rome (approximately the eighth century B.C.), its people relied on a local lunar calendar to keep track of seasons and religious ceremonies. A lunar calendar is one based on the phases of the moon instead of, like today’s calendar, on the Earth’s relationship to the sun. This ancient Roman calendar included ten months of 30 or 31 days each, and the new year began in March. (In the beginning, then, September, October, November, and December really were the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth months, as their names indicate.) The resulting calendar year contained only 304 days, which were followed by an uncounted winter season.

According to tradition, the second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, decided he wanted wintertime on his calendar, so he added the months of January and February to the end of the year, creating a 354-day calendar. This was followed soon after with a similar Roman republican calendar that had 355 days. In 153 B.C., the start of the new calendar was pushed back to January 1 — after the Senate saw some push-back from an angry mod of citizens.

To keep the dates in sync with the seasons, the people in charge of the calendar occasionally added weeks or even a whole month to the calendar to realign the dates. Unfortunately, those “people in charge of the calendar” were politicians, so new days were sometimes added sporadically and for the wrong reasons, including to extend one’s term in office.

In the mid-first century B.C., the calendars had become so misaligned with the seasons that the vernal equinox, usually in the last third of March, was falling in the calendar in the middle of May. Julius Caesar, by this time emperor of Rome, had had enough. He called on a top astronomer to offer a solution to the mess that was the Roman calendar.

The result — what we today call the Julian calendar — was a solar (or tropical) calendar, giving up all pretense to being guided by the moon’s phases. It recognized that a solar year was 365.25 days long (which is close to being accurate, but not spot on), and so it established that a regular calendar year would contain 365 days, and every fourth year would have one extra day added to it. It also reaffirmed that the new year would begin on January 1.

So we have arrived at the modern idea of the leap year, but the Romans didn’t call it a leap year, and that extra day isn’t the one you think it is. With the old lunar calendars, the days of the month weren’t simply numbered consecutively; they were named by counting backward from the next calends (the first of the month, coinciding with the new moon), ides (middle of the month, on the full moon), or nones (approximately nine days before the ides). This system wasn’t abandoned in the new Julian calendar.

When it came time to decide where to put that extra day every fourth year, Caesar and his astronomers didn’t stray from older calendar traditions: They decided to add that extra day where they had been inserting extra days for centuries — after the sixth day before the calends of March. That means, from a certain point of view, a second sixth day before March 1 was added to every fourth year. And this is where our word bissextus comes from.

Bissextus, or the bissextile day, comes from the Latin bis “twice” + sextus “sixth.” A leap year is also known as a bissextile year. We refer to February 29 as “leap day,” but to purists, that added bissextile day was actually last Monday, February 24.

The Julian calendar, with some later, minor adjustments (including a modern numbering system), sufficed for centuries. But a solar year is actually 365.242199 days long, not the nice round 365.25 that Caesar’s astronomer reckoned. By the mid-16th century, the Julian calendar was off by about 11 days, which was causing problems with the calculation of religious holidays.

A new solution was issued in 1582 as a papal bull from Pope Gregory XIII. The Gregorian calendar — which is what mall calendar kiosks are selling every November and December — eliminated 10 days from October of that year, thus realigning the spring equinox to March 21. It also established a new calculation for leap years: For centennial years, only those divisible by 400 would be leap years. The year 2000, then, was a leap year, but 2100, 2200, and 2300 will not be.

Protestant countries weren’t so keen on this new calendar because of its source, so it took time before it was widely adopted. England and its colonies didn’t adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1752, which is why George Washington, for example, appears to have two birthdays in 1731: February 11 according to the Julian calendar his parents would have used when he was born, and February 22 according to the Gregorian calendar we use today.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: A Carnival of Names for Mardi Gras

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Shrove Tuesday, Fat Tuesday, Mardi Gras, Pancake Day. The Christian holiday celebrated this year on February 25 goes by many names, and not all of them make sense at first blush. So what does the day mark, and where do all these names come from?

You can’t talk about this holiday without talking about Lent, the period of fasting and personal sacrifice that begins on Ash Wednesday (February 26 this year) and lasts for 40 to 46 days, depending on how it’s counted. (Though Lent began as a tradition in the Catholic church — whose official language remains Latin — the word Lent comes from an Old English word meaning “springtime.”) Modeled after Jesus’ 40-day fast in the desert, Lent is a time of spiritual preparation for Easter, the most important celebration on the Christian liturgical calendar. The day before Ash Wednesday, then, is a time to prepare for Lent — and people go about it in different ways.

Shrove Tuesday

The word shrove is a past-tense form of shrive “to take confession.” Someone who has confessed their sins and repented is shriven. Shrive comes from an early borrowing into Old English of the Latin scribere “to write” — the source of scribble, script, and scripture — which then evolved within the English idiom. Shrove Tuesday, then, came up through Anglo-Saxon Christian tradition. On Shrove Tuesday, parishioners go to the confessional to be absolved of their sins before the Lent — a sort of spiritual cleaning out before the fast begins.

Pancake Day

Another thing that needs to be cleaned out before a fast is the pantry. The day before Ash Wednesday is the last day to use up rich ingredients that should be avoided during the Lenten season, including sugar, eggs, and fats. Throw in a bit of flour, and what’ve you got? Pancakes! It has become a tradition in many places, especially in Europe, to make pancakes on the day before Ash Wednesday. In fact, in some communities, the people are called to confession by the ringing of a bell which some people call “the pancake bell.”

Fat Tuesday and Mardi Gras

If we’re eating all the rich foods in our pantries at once, what we’re really talking about is a feast. And eating all that food can leave a person feeling, well, fat. Hence, Fat Tuesday, which in French is Mardi Gras, a last chance for overindulgence (in more ways than one) before the weeks of fasting and sacrifice begin. French-founded New Orleans — where they celebrate with king cakes instead of pancakes — usually has the largest Mardi Gras celebration in the United States every year.

Carnival

Whether you call it Shrove Tuesday, Pancake Day, Fat Tuesday, or Mardi Gras, it’s just one day on the Christian liturgical calendar. In many places, that one day is the culmination of days- or weeks-long celebrations leading up to Lent. Some places have a whole carnival season.

In Rio de Janeiro, massive public Carnaval celebrations begin the Friday before Ash Wednesday (that’s tomorrow!), offering an extra-long weekend packed with food, street parties, parades, and samba dancing. In Italy, Venetians commit most of February to the Carnevale di Venezia, the famous Carnival of Venice.

The word carnival — from the Italian carnevale, which is a shortening of the earlier carnelevare — comes from the Latin caro “flesh, meat” and levare “to remove, to raise.” Part of the Lenten fast involves giving up meat on specific days, so the world carnival fits right in whether you think of it as meaning “to raise meat up” or “to remove meat.”

Carnival entered the English language in the mid-1500s specifically in reference to the celebrations before Lent, but by the end of that century, the word was being used to indicate revelry more generally. The “traveling amusement fair” type of carnival is a much more recent invention that followed the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which featured the world’s first Ferris wheel.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Logophile: So Much to Love

The word logophile stems from the Greek roots logos “words” and philein “to love” — a logophile is someone who loves words. But there are so many things in this world to love! Can you match up these other –philes with the objects of their affection?

Match the Word with the Thing Loved

-

- An anthophile loves …

- An ailurophile really appreciates …

- A chionophile is keen on …

- A cinephile quite enjoys …

- A cynophile just adores …

- An oenophile can’t get enough of …

- A pogonophile treasures …

- A selachophile is enchanted by …

- A selenophile prizes …

-

- beards

- cats

- dogs

- flowers

- the moon

- movies

- sharks

- snow

- wine

Answers

- d

- b

- h

- f

- c

- i

- a

- g

- e

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: 9 Things You Didn’t Know Were Named after People

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

A word that is based on or derived from someone’s name is called an eponym. And, in a symmetrical turn, an eponym is also the person after whom something is named. The word sideburns, for example, is an eponym, and so was General Ambrose Burnside.

Eponyms are legion, from the names of chemical elements (like einsteinium and curium) to plants (forsythia, magnolia) to units of measurement (volts, watts) to brand names (from Adidas to Zamboni). Most of these we recognize as eponyms right away. But not all eponyms are so obvious.

Here are nine fairly commonplace things that you might not know derive their names from real-life people.

Algorithm

Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi was the eight- and ninth-century Persian mathematician and astronomer who is widely considered the founder of algebra. As his mathematical treatises filtered westward, his surname al-Khwarizmi (which means “of Khwarazm,” now the city of Khiva in Uzbekhistan) was transliterated (and somewhat mangled) into Medieval Latin as algorismus. This entered Old French as algorisme which, later, because of a mistaken belief that it was related to the Greek arithmos “number,” changed into algorithme, which became the English algorithm.

The word algebra itself comes from the Arabic word al-jabr in the title of al-Khwarazmi’s treatise on equations, Kitab al-mukhtasar fi hisab al-jabr wal-muqabala, “The Compendium on Calculation by Completion and Balancing.”

Boycott

Boycotting got its name from the man against whom the first organized boycott was aimed. Charles Cunningham Boycott was hired by aristocratic land owners to collect rent from Irish tenant farmers during a famine in 1879. When he tried to evict 11 farmers for failure to pay, the Irish National Land League rallied, convincing townsfolk in the area to cut off all business with the man — even the delivery of his mail. I dug into the history of this word in much greater depth in “The First Boycott.”

Caesar Salad

Okay, so you already knew this was named after a person — but it might not be the person you think. Roman emperors have nothing to do with this salad; it was named after Caesar Cardini, the restaurant owner who created it. As the story goes, on July 4, 1924, a rush of diners to Cardini’s Tijuana restaurant put a strain on his pantry, and, out of necessity, he crafted the new salad from the ingredients he had to keep his customers full.

Derrick

Before derrick referred to a structure over an oil well to support the drilling apparatus (from the 1860s) or to a crane-like construction used for hoisting heavy loads (from the 1720s), a derrick was a more specific and malevolent structure: a gallows. During the 17th century, a London executioner named Derick became so well-known — presumably because he was often in the public eye, a scary thought — that people named the gallows at Tyburn after him. Derick was also used as the name for a hangman. As public hangings became less common, the word found new uses for nonlethal support structures.

Guy

Guy is such a generic word now that it might be hard to believe that it traces back to a specific man: Guy Fawkes, who was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered for his involvement in a plot to blow up the British Parliament in 1605. I wrote more about the history of guy (and of Guy Fawkes) in “Bad Guys and Good Guys.”

Leotard

Named for its inventor, Jules Léotard, a popular French trapeze artist from the mid-1800s, the tight-fitting one-piece garment quickly became popular for dance, gymnastics, and other disciplines that involve a lot of movement.

Nachos

The veracity of the commonly told story about the invention of nachos is questionable, but that story has taken on a near-mythological status. In many ways it mirrors the story of the first Caesar salad.

According to an article in the San Antonio Express on May 23, 1954, a restaurant in the Mexican border town of Piedras Negras was running low on supplies sometime in 1940. Ignacio Anaya Garcia — a waiter, chef, or maitre d’ who had hungry diners to satisfy — came up with a new dish from the foods he had on hand. Ignacio’s nickname was Nacho.

The story may be apocryphal — and we may never know for certain — but one surprising fact shouldn’t be overlooked: Nachos were invented in the early 1940s. The first modern World Series was held in 1903. That means baseball fans attended nearly four decades of World Series playoffs without being able to buy nachos at the snack bar.

Nicotine

The tobacco plant genus Nicotiana was named for the French ambassador to Portugal who, in 1561, sent tobacco seeds and powdered leaves to France. The name of the poison in tobacco leaves, nicotine, was then derived from the scientific name in the early 1800s. His name has been going up in smoke ever since.

Shrapnel

In 1784, then-Lieutenant George Shrapnel of the Royal Artillery invented a new type of ammunition — a hollow cannonball filled with lead shot, which would explode in mid-air and send hot lead in all directions. He called it “spherical case ammunition,” but when the British army in the early 1800s adopted similar ordnance, but conical instead of spherical, it and the fragments it produced took on his name.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: What Is a Caucus Anyway?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

While the Iowa Republican Caucus proceeded easily this week, with a basic secret ballot and no real challenger to the incumbent president, the Democratic Caucus didn’t go quite so smoothly. Not only do Democrats have more candidates to choose from, but they also rely on a more complicated caucus system that involves voters at more than 1,600 locations physically moving around the room to show their preferences.

And while many have been wondering about the process, the outcome, and the future viability of such a system, some of us spent our time wondering, “Where does the word caucus even come from anyway?” That turns out to be a more difficult question to answer than “Who won the Iowa Democratic Caucus?”

Why? Because no one really knows for sure. Merriam-Webster Dictionaries lists the etymology of caucus as “origin unknown.”

Although we don’t know the word’s precise origin or derivation, there are some things we definitely do know about the word, and there are theories beyond that. Here’s what we do know about the word caucus:

- It means “a closed meeting of a political party called together to choose candidates or decide policies,” and it can be used as a verb to mean “to gather for such a meeting.”

- It is not related to caucasian. (That word, which originally indicated “of or from the Caucasus Mountains,” took on its current meaning starting in 1795 through the work of German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.)

- It’s primarily an American word. In the U.K. (and other English-speaking countries with a parliamentary government), you won’t find references to political caucuses — though there was a “caucus-race” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, so the word must have meant something to the Victorians.

- It’s definitely not a Latinate word, which means its plural is caucuses. (Don’t even try to pull cauci on anyone.)

According to Merriam-Webster, John Adams reported in February 1763 of the upcoming meeting of “the Boston Caucus Club,” a group of city elders doing just what a caucus does today: choosing who will fill which positions in the local government. Why he chose that word is a something of a mystery.

The primary theory about the word’s origin is that it comes from the Algonquian word caucauasu. Algonquian is a Native American language group that was widespread in the North and Northeast and is the source of such common English words as moccasin, chipmunk, and Wyoming. In a Virgina dialect, caucauasu meant “elder, advisor.”

But while Adams’ Caucus Club was ostensibly a political gathering, it was also a social one. It’s possible that the word was derived from the Modern Greek kaukos “drinking cup,” something one might find in large quantities at a Caucus Club meeting.

It’s doubtful that Adams himself coined the word. Though his Caucus Club announcement is the word’s first appearance in print in a political context that we know of, it likely was had been circulating for some while in speech and in other documents that have been lost to time. And the longer it circulated, the more opportunity it had to evolve from its earliest iterations.

So we’re left only with theories. Unless new historical documents are uncovered pointing a clearer way to the beginning of this word’s history, we may never truly know where caucus came from.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Condominium: All Together Now

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

A hundred years ago, if you told someone you lived in a condominium, they might ask if you were from the New Hebrides, an island group northeast of Australia. That’s because the modern condominium — an apartment that is owned rather than rented — didn’t appear until the late 1950s. Before that (and still today), condominium was a term of international law that referred to a territory ruled jointly and equally by multiple sovereignties. The New Hebrides, for example, were jointly controlled by the French and British governments throughout most of the 20th century.

The word condominium comes from the Latin prefix com- “with, together” (which becomes con- before a D) plus dominium “property, right of ownership,” the source of the word dominion.

How did condominium make the journey from an entire owned-together-land to the modern living space? It makes sense if you think not of a single condo but of the entire building that dwelling is part of. That building is equally and jointly owned by the individual homeowners in much the same way a string of islands might be equally “owned” by multiple governments.

Condominium makes etymological sense for the name of an owned apartment, too, if you take its roots back even further. That Latin dominium derives from dominus “lord, master,” which comes from domus “house” — also the source of domicile and domestic. So a condominium is not only a jointly owned dominion, but, since the late 1950s, a jointly owned house.

As for that one-time condominium called New Hebrides, its people achieved independence in 1980 and renamed their domain the Republic of Vanuatu. And I bet they have some great condos on the beach.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: From Probate to Reprobate

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

We rarely see the words probate and reprobate used together, so we can probably be forgiven for not having noticed that the latter is just the former with re- affixed to it. That being the case, does that mean the two words are etymologically related?

Short answer: Yes!

Probate court deals with the disbursing a deceased’s property according to his or her last will and testament. But a probate lawyer’s responsibility isn’t simply to read the will and do what it says; the crux of probate law is proving the authenticity and legality of the will itself before it can be exercised. Like most legal jargon, the word probate comes from Latin, in this case from the verb probare “to try, test, or prove.” The word prove itself stems from the same root.

We all know that the prefix re- often indicates a doing-again, as in reprint, reload, realign, and refresh. So we might conclude that reprobate means something like “prove again” or “something that is proven a second time” — but it doesn’t. In common language, a reprobate is a depraved person, a scoundrel. So what gives?

That re- prefix can also mean “back, backward,” as it does in the words recall, regurgitate, and recede. In some words, it isn’t perfectly clear which meaning a re- prefix indicates, because doing something again can involve going back to the beginning. Consider, for example, rejuvenate. Juvenis is the Latin word for “young” (whence juvenile); whether rejuvenate means “to be young again” or “to go back to youthfulness,” the outcome is the same.

But reprobate isn’t in that gray area. The re- prefix can only indicate “back,” and more than just backward motion, but the opposite of what follows it. So reprobate breaks down etymologically to “not proved.” In the early 15th century, the word took root in English as a verb, first meaning “disapprove” but quickly taking on the stronger meaning of “reject, condemn.” By the mid-16th century, the verb had evolved into a noun meaning “one who is condemned” (that is, by God).

Though the religious connotation has faded, a reprobate is still not something one wants to be. Probate court was established in large part to guard against reprobates who would submit counterfeit wills naming themselves heirs to family fortunes.

Reprobate as a verb is still around, too, but usually only in legal jargon. If a probate lawyer reprobates a will, that means it is rejected. Its opposite, approbate, means to accept a will as legal and genuine.

The legal terms probate, reprobate, and approbate have the more common (and closely related) counterparts prove, disapprove and disprove, and approve. We also have the word reprove; its original meaning was “refute,” but with both disapprove and disprove edging in on its territory, reprove evolved to mean “scold or censure.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Martial and Marshal

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

Though the words martial and marshal sound alike and both have a long history in the language of war, these two homophones derive from two very different sources.

The adjective martial, part of the English language since the 14th century, comes from the name of the Roman god of war, Mars. Martial originally meant “of or pertaining to war,” and by the end of the 15th century was extended to mean “pertaining to military organizations.” That’s what it indicates in court-martial (a trial conducted by and for the military) and martial law (in which the law is maintained by military forces rather than a civilian police corps).

You might notice that the name of the god Mars has spawned two separate adjectives: martial and Martian — the latter referring to aspects of (and beings from) the planet named after him. He’s not the only god to have created such a lexical split: From Jupiter — also called Jove — we derive both jovial and Jovian, and from Mercury we get mercurial and (the fairly rare) Mercurian.

Marshal has a different history. It entered English from French, which is a Romance language, being derived from Latin. But it doesn’t all come from Latin: Like guy, marshal began its etymological journey from German, specifically from the Germanic Franks. The Old High German marahscal was a compound comprising marah “horse” (the source of the English mare) and scalc “servant.” The original “marshals” were the people in charge of the horses.

Remembering that marshals once corralled horses can help you remember that marshal is the spelling of the verb in phrases like “marshal your forces.” Marshal as a verb is practically synonymous with corral in a metaphorical sense.

As horses became more important in war efforts — we’re talking a millennium and a half ago here — so did the marshals who took care of them. By the time the word entered Old French, as mareschal, the term had become a title for a high-ranking army general. The word continued to evolve in French so that, by the time it was adopted into English in the 14th century, it was a high-ranking royal officer.

Since then, marshal has found a varied life in the language, from the law enforcement efforts of the U.S. Marshals Service to the ceremonial grand marshal of your local Independence Day parade.

Finally, neither martial nor marshal should be confused with the double-L-ended proper noun Marshall, as in the names of Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan; Marshall Field, who founded the department store that bore his name; former U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall, who came up with the Marshall Plan; and British naval captain John Marshall, for whom the Marshall Islands are named.

And no, people from the Marshall Islands aren’t called “Marshians”; they’re Marshallese.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Trivia Three Ways

With the Jeopardy! The Greatest of All Time tournament in full swing, many of us are boning up on our trivia to try to compete — from the comfortable, low-pressure environment of our own living rooms — with Ken Jennings, Brad Rutter, and James Holzhauer. It seems a fitting time, then, for some trivia trivia:

The word trivia was originally the plural of the Latin trivium, which breaks neatly in half: the tri- indicates “three” (as in triple and trinity), and -vium comes from the Latin word for “road.” A trivium was a place where three roads converged. These intersections naturally became places where travelers, strangers and friends alike, commonly met, so the adjective form of the word, trivialis, came to mean “public” and then more broadly “commonplace.” By the mid-16th century, English had adopted trivial to mean “commonplace, ordinary.”

But, like the roads at a trivium, the word trivia took another course as well. In Roman mythology, the goddess Diana is a triple deity, meaning — depending on your interpretation — that she is three deities worshiped as one or one deity worshiped in three discrete aspects. In her triple aspect, she was referred to as Diana Trivia, a three-way Diana, representing the convergence of Diana, goddess of the hunt (Artemis in Greek mythology); Luna (Selene), goddess of the moon; and Hecate, an ancient underworld deity and the goddess of witchcraft, who helped Ceres (Demeter) search for Proserpina (Persephone) after Pluto (Hades) kidnapped her. Hecate would become Proserpina’s companion during the third of each year Proserpina was confined to the Underworld.

In 1716, English poet and playwright John Gay brought these two etymological courses together, choosing Trivia as the name for his goddess of the streets in the poem “Trivia; Or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London.” Almost two centuries later, American author Logan Pearsall Smith, influenced by Gay’s poem and his own knowledge of etymology, published a book simply titled Trivia. Smith, however, leaned more heavily on the “commonplace” aspect than the “goddess” one. Privately published in 1902 and then republished by Doubleday in 1917, this somewhat popular book was a collection of short pieces (some only a sentence long) about small, commonplace experiences and events.

Smith’s book sparked new life into the word trivia as a word for commonplace events, and then by extension as facts about commonplace things. By the mid-1960s, trivia games, in which players would quiz each other about otherwise useless bits of information about pop culture, had become a fad among college students.

In 1981, while those former ’60s college trivia buffs were building families, the Trivial Pursuit board game was released and became an immediate hit. (Here’s some trivia: The game was invented in Canada.) Sales of the game peaked in 1984, which — coincidence or not — was the same year that the game show Jeopardy! was relaunched with Alex Trebek (also Canadian) as host, and it’s been going strong ever since.

Now, it wouldn’t be fitting for a word based on the coming together of three roads to go in only two directions, would it? There is a third word route here, and it was actually the word’s first use in English: In early 15th-century academics, the trivium was the first three liberal arts — grammar, rhetoric, and logic — and trivial was an adjective meaning “from the trivium.”

Considering all the threesomes inherent in the many lives of trivia, is it a coincidence, then, that Jeopardy! features three contestants, and not two or four?

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: A New Year’s Resolution

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The beginning of a new year, everyone is talking about New Year’s resolutions. Should you try to lose weight? Save money? Find a new job? If your resolution is to learn more about the history of the English language, you’ve come to the right place, and you can start fulfilling that resolution with a look into the word resolution itself.

The word finds its roots in the Latin resolutionem “the process of reducing things to simpler forms,” from resolvere “to loosen.” The prefix re- in this case indicates not a repetition but an intensification. So from the Latin solvere “to loosen, dissolve,” resolvere indicates a complete breaking down into constituent parts.

We find this definition in common use during Shakespeare’s time. For example, in Hamlet, written in 1599 or 1600, we find the mopey prince mumbling, “O that this too too solid flesh would melt, / Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!”

When you break down something into its individual parts, it can help you better understand the whole. It’s this concept that mathematicians took hold of when they found a use for resolution to describe taking apart complex systems and breaking them down into numbers and figures. In the mid-16th century, mathematicians began resolving complex mathematical problems. Then it extended into other situations — such as resolving conflicts or disagreements, almost as if they were equations. In math, resolving a problem to discover its resolution eventually gave way to the more common solving of a problem to find a solution. But in other areas, resolution stuck around, and new meanings piled on.

Extending the idea further, someone who seemed to have solved all their problems, showing little doubt in their decisions, was considered resolute. For larger community problems, possible resolutions were written down and discussed in local councils. Thus we get the legal sense of a resolution, which could then be debated, voted upon, and passed into law.

Over the last several centuries, new meanings of resolution have retained some reference to the small, constituent parts but have focused more on bringing together the whole rather than breaking it apart. (This is in part because the related word dissolve covers a lot of the same old ground.) In literature, the resolution is when all the individual threads of a story come together and work themselves out. In music, chord resolution is the passing from a dissonant to a consonant chord — the resolution is determined by the movement of the constituent notes, but it’s the chords that resolve. And in digital imagery, resolution is the measure of individual dots of color (pixels, ink) used to create an image, but it’s used practically as a measurement for how clear and detailed the image as a whole is.

But this is a new year, so what about New Year’s resolutions? That phrase started appearing in the late-18th or early-19th centuries. It probably comes from the idea of being resolute — of choosing a personal problem and making a promise to find its solution. But a successful new year’s resolution, as most know, doesn’t aim vaguely at some large, ultimate goal, but focuses on the smaller, constituent actions one needs to achieve it: Not “I’ll save $1,000,” but “I’ll put away $20 a month.” Not “I’ll lose 40 pounds,” but “I’ll limit myself to one pizza per week and hit the gym three days a week.”

Here at the Post, we wish you good luck with whatever resolutions you’ve made for the coming year.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Time to Relax

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

This last week of the year is a time when many of us, having overworked ourselves throughout the rest of the year, try to cram in our last allotted vacation days at work before we lose them. That time off lets us relax and enjoy the company of friends and family.

With Christmas over, it’s theoretically easier for millions of people to relax, but with Hanukkah and Kwanzaa still in full swing, New Year’s Eve parties to plan, other remaining obligations with families on the books — and especially if you’re one of the skeleton crew keeping the business afloat while everyone else is away — we are perhaps not getting as much R&R as advertised.

So take a moment right now to pause. Take a deep breath, let it out slowly, and allow your mind and your muscles to lose their tension. Keep reading, and together we’ll do a little relaxing.

One of the joys of being a word lover is looking more deliberately at words we use every day and seeing patterns that we might normally miss. Take relax, for example. Re- + lax; does it really mean “to lax again”? Not precisely, but that’s not far from the truth: The word traces back, through Old French, to the Latin relaxare “loosen, stretch, or widen again,” from that re- prefix and laxare “loosen.”

Relax found its way into English in the late 14th or early 15th century, but in the beginning it existed only in the transitive sense — that is, it required a direct object. For centuries, you could “relax your grip” or “relax a knot,” for instance, but it wasn’t until the early 1930s that the intransitive sense caught on, and you could take time off work to just relax.

Which is what I hope you get to spend some time doing over the next week. There’s a lot of tension in the world, and it is good for our minds, our health, and our souls to find a few minutes every day to relax.

Need more relaxation? From our 5-Minute Fitness series, here are a breathing technique to help de-stress, a simple stretch to help soothe your neck, and a simple exercise to help stretch away stress.

Featured image: Shutterstock

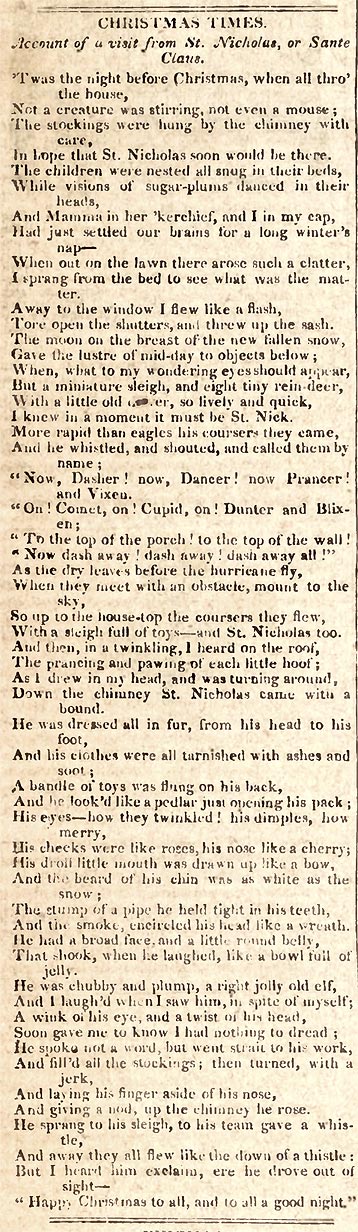

In a Word: Eight, er, Nine Tiny Reindeer

Today, we all know the names of Santa Claus’s nine flying reindeer — or at least we think we do. But what is behind those names, and which ones have changed over the last 200 years?

January 7, 1826

The names of eight of those reindeer first appeared in the poem we know today as “The Night Before Christmas.” It was first published anonymously on December 23, 1823, in a newspaper in Troy, New York and became an immediate hit that was published and republished for years in papers across America under the title “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The Saturday Evening Post even printed it in its January 7, 1826, issue.

But the man responsible for penning the poem remained a mystery until 1836, when Clement Clark Moore, a Bible professor from New York City, took credit for it. He even included it in a volume of his poetry published in 1844. However, the family of another New Yorker, Henry Livingston Jr. — who died shortly after the poem’s first publication and before Moore took credit — have long claimed that he was the poet. More recent research has reinforced that argument.

Regardless of who wrote the poem, it is the first to include Santa’s reindeer and call them by name. They weren’t names passed down from Old World folklore, but were created by the poet. Whether they were chosen for their meanings, their colloquial connotations, or simply for their rhythm and rhyme, we’ll never know. But the names do have some history, and they perhaps aren’t all exactly as you remember them.

Dasher

A dasher is simply one who dashes. Dash appeared in Middle English as dasshen in the 14th century, probably from the Middle French dachier “to drive forward.” Two types of “dashing” appeared in English at about the same time: There’s the “moving quickly” dashing, as in “dashing off to the store,” and there’s the “striking suddenly and violently” dashing, as in “being dashed against the rocks.” The poet probably had speed in mind when he chose this name — it is, after all, a poem for children — but some writers do have a knack for slipping in opaque little adult-themed jokes in their children’s stories.

If there is an adult insinuation here, there’s an even more frightening possibility. By 1800 — meaning it likely would have been known to the poet — dash was also being used as a euphemism for damn. Considering that Santa Claus’s raison d’etre is to be extremely judgmental of children, having a reindeer that hints at the ultimate naughty list wouldn’t be out of place. (It’s unlikely, sure, but not implausible.)

Dancer

Dance — from which the name Dancer is formed — has an unexpectedly muddied history. We know it entered Middle English in the 1300s as dauncen, from Old French dancier “to dance,” but that’s where certainty stops. Though French is well known as a Romance language — that is, it’s derived from the language of the Roman Empire — dancier isn’t derived from Latin: The Latin word for “dance” is saltare. Etymologists aren’t certain exactly where dancier came from; it’s possibly from an old Frankish dialect that predates the expansion of the Roman Empire into northern Europe.

Prancer

The history of prance is similar to that of dance. It, too, appeared in Middle English in the 1300s, as prauncen, and its ultimate source is debatable. Some theories about its provenance include the Middle English pranken “to show off,” from the Middle Dutch pronken “to strut, parade” (and the source of our word prank), or from a Danish dialect word prandse “to go in a stately manner.”

Regardless of where it came from, the word was originally used to describe horses — and it eventually found its way, in this poem, to a different hoofed animal.

Vixen

Going back to Old English fyxen, vixen is a feminine form of fox. Today, vixen is more commonly used to describe a sexually attractive woman — especially on the big screen — but that extended meaning hadn’t been established until the mid-20th century, so the poet couldn’t have been hinting at that. But there was another extended meaning of the word that had been around for centuries by the time the poem was written. Even dating back to the time of Shakespeare, vixen was a derogatory term meaning “an ill-tempered woman.” The poet certainly would have understood this meaning, so this particular choice of name is interesting.

Comet

The Great Comet of 1811 was a memorable marvel that the poet most certainly would have experienced. It was visible to naked eye for 260 days in 1811 — a record that stayed untouched until the Hale-Bopp comet of 1997 visited our solar system. A mysterious body that hurtled through the night sky must have seemed the perfect name for a reindeer that did the same thing.

Comet itself goes back to the Greek kometes “long-haired,” describing the comet’s tail in the night sky. It journeyed from Greek through Latin and Old French before arriving in English sometime before the 12th century.

Cupid

Cupid was the Roman god of erotic love, the son of Venus and Mercury. (Greek mythology gave him the name Eros.) This seems like an odd choice for the name of a reindeer in a Christmas poem that has nothing at all to do with sex or romance. However, Cupid had long be depicted as a winged god, so perhaps it was his ability to fly that the poet had in mind when he named this reindeer.

The Donner Party

This is where it gets a little weird: When the poem was first published, there was no Donner in it. The next reindeer on the list was Dunder, which was, according to Snopes, part of a common Dutch exclamation, “Dunder and Blixem!” — meaning “thunder and lightning.”

Henry Livingston Jr., it should be noted, had a Dutch background, while Clement Clark Moore came from British stock.

Another publisher soon changed Dunder to Donder, perhaps to more closely mimic the common pronunciation. (The Post seems to have rendered it as Dunter when we printed it in 1826. Was this an editorial decision or a printmaker’s error? We may never know.) When Moore added the poem to his collection in 1844, he retained this change to Donder.

Donner (the German word for “thunder”) wouldn’t make an appearance until the turn of the century, and it wouldn’t be cemented in our collective conscience until 1949, when Gene Autry popularized the Johnny Marks song “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

From Blixem to Blitzen

And yes, the last of the reindeer named in the poem was originally called Blixem, the Dutch word for “lightning.” This was changed in pretty short order to Blixen, probably to better rhyme with Vixen. (The Post used Blixen in 1826.) In 1844, when the poem appeared in his collected works, Moore — perhaps knowing more German than Dutch — changed the name to Blitzen, the German word for “lightning.” But if Moore did know German, it is odd that he kept the spelling Donder instead of altering it further to Donner, as we know it today.

Rudolph

Glowing-nosed Rudolph was a latecomer to the herd. Created by Robert May in 1939, the story of Rudolph was created as part of a Montgomery Ward Christmas promotion — a giveaway to children who visited Santa in their stores that year. Rudolph didn’t become a mainstay of Christmas in America until, as I mentioned earlier, Gene Autry recorded and popularized “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1949.

The name Rudolph comes from the Old High German Hrodulf and literally means “fame-wolf” — an odd choice for a character depicted as a handicapped underdog. May wasn’t thinking about etymology, though. The name was chosen primarily for its alliteration; documents show that, as he was working out the story, May scribbled down a number of other possible names — including Rollo, Reginald, and Romeo — before deciding on Rudolph.

Featured image: “Reindeer in the Night Sky” by Manning de V. Lee, Dec 1, 1954. Copyright © SEPS.

In a Word: Stoked for a Chauffeur

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

As the days get colder and colder, many of us start our mornings silently wishing we had a chauffeur, maybe not even to drive us to work, but at least to venture out in the frigid air and warm up the car. Both acts, it turns out, are historically within the purview of chauffeurs.

The word chauffeur, you probably have guessed, comes from French. Specifically, it relates to the verb chauffer, meaning “to heat,” and chauffeur meant “one who heats” — literally a “stoker.” The first chauffeurs worked on railroads and steamships; their job was to keep the steam engine hot and running. Some of the first automobiles were steam-powered, too, and chauffeurs were employed to keep them running as well.

Employed is an important word there: These early French automobile chauffeurs worked with other people’s cars, sometimes not only maintaining the engines but actually driving the cars’ owners around town. As gas-powered engines became the norm, chauffeurs were no longer needed in their original stoking sense, but they did stay on as drivers, and their title stayed with them. And it was this sense that the word carried with it when it was borrowed into English in the late 19th century.

Chauffer and chauffeur trace their roots back to the Latin calere “to be warm,” making them etymological relatives of words like chafe, cauldron, calorie, chowder, and even nonchalant, some of which I may take a closer look at in later columns.

But for now, I’ll continue to trudge out into the cold morning on my own, sit in my cold car as the engine warms, and fight the urge to order up a nice toasty Uber.

Featured image: Pixelcruiser / Shutterstock.

In a Word: Cornucopia: A Thanksgiving Symbol that Predates America

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

The cornucopia has long been a symbol of the Thanksgiving season — a large (often wicker) horn overflowing with fruits and vegetables and grains. It’s also known as the horn of plenty, and for good reason. The word cornucopia comes from the Latin cornu “horn” (also the source of unicorn) and copiae “abundance.” The phrase “horn of plenty,” is a literal translation of the elements of cornucopia.

Though the horn of plenty is today a symbol of Thanksgiving, the first cornucopia comes from ancient Greek mythology, all the way back to the childhood of Zeus, King of the Gods. If you think back to your mythological original stories, you might remember that Zeus’s birth and early childhood were not exactly pleasant. Zeus’s father, the Titan Cronus, had heard a prophecy that he would be usurped by one of his children. So whenever his wife Rhea gave birth, the power-hungry Cronus immediately ate the child. He ate five children in all, swallowing them up soon after they were born.

After the fifth child, Rhea showed some maternal attributes and decided to protect the next one. When their last child, Zeus, was born, Rhea rescued him by replacing the child with a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which Cronus gulped down without a second thought. In the meantime, the real baby Zeus was secreted off to a cave on the isle of Crete.

The tales of Zeus’s upbringing on Crete are about as consistent as Spiderman origin stories. But like Spiderman origin stories, though the details differ, the main themes persist throughout. One of those consistent themes is the existence of a goat. It might have been a magical goat named Amalthea, or Amalthea might have been a nymph or a daughter of the Cretan king Melisseus who owned a goat. At any rate, it was that goat’s milk that nourished the infant Zeus.

At some point in Zeus’s young life, the goat lost a horn — either it fell off, or Zeus accidentally or intentionally tore it off. And then, one of two things happened: Either the nymph Amalthea filled the horn with herbs and fruits to feed Zeus, or Zeus endowed the horn with the ability to provide its possessor with whatever they wished. The horn was called, in Greek, keras amaltheias “The Horn of Amalthea,” and in Latin, cornu copiae — what became the modern cornucopia. That cornucopia, a symbol of the abundance, is a common theme in ancient Greek art, and it makes an appearance in other mythological stories.

After the goat died, Zeus used its hide to create the aegis, either an impenetrable shield or armor that was later used by Athena. Zeus, though, used the aegis to defeat Cronus and the other Titans and rescue his five siblings from his father’s stomach.

That’s right: They were there the whole time in his stomach. Remember that after you’ve gorged yourself on Thanksgiving dinner: No matter how full you feel, it couldn’t possibly be worse than having five grown deities and a baby-sized stone lodged in your gut.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com