The Rockwell Files: Best Job Ever

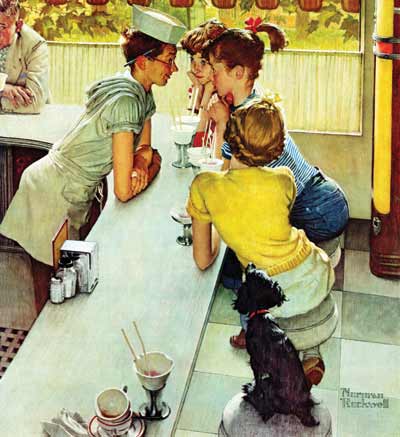

Rockwell’s inspiration for this August 22, 1953, cover illustration grew out of stories his son Peter told of working a soda counter one summer. Peter even posed as the young man when Dad painted the scene. When his father showed him the final product, Peter didn’t like it. He claimed he “wasn’t that goofy looking.”

In an earlier draft of the illustration, the counter was more crowded. A gentleman’s balding head was visible in the foreground, and a mother and son sat at the far end of the counter. But Rockwell removed them so he could draw viewers’ attention to the mid-canvas drama, where a boy and three girls stare at each other across a counter with rapt attention.

As always, Rockwell adds numerous masterful details, like the reflection of the sugar dispenser in the napkin holder, the grated floor that would prevent slipping on spills, and the vintage Wurlitzer jukebox just visible at the right edge. And that man in the corner? We can pretty easily guess what he’s thinking: Hot fudge! Ice cream! Girls! Why weren’t there summer jobs like this when I was young?

This article is featured in the July/August 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

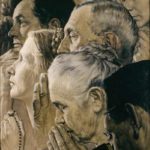

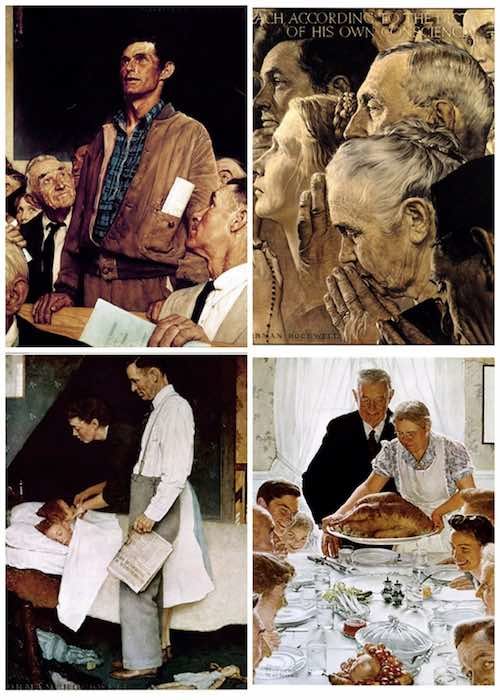

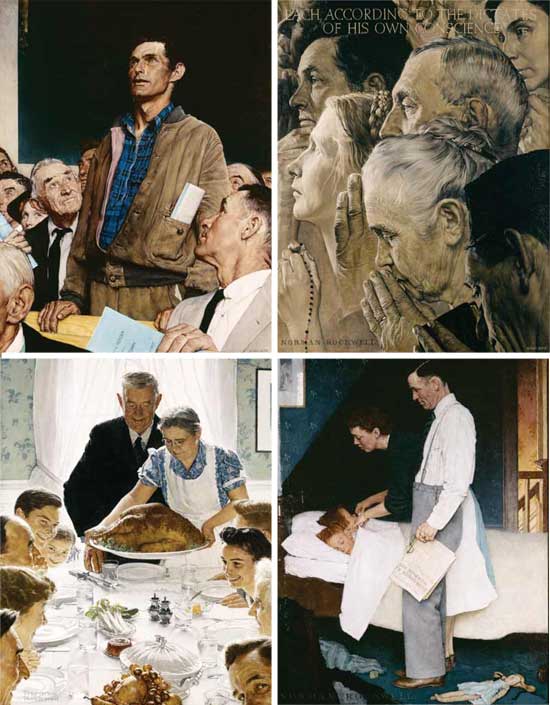

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms

“We look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want … everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear … anywhere in the world.”

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Message to Congress, January 6, 1941

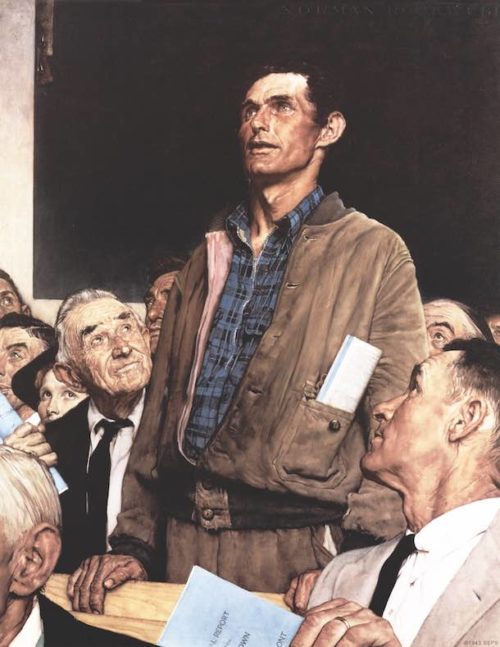

Inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech to Congress on January 6, 1941, on the eve of World War II, Norman Rockwell wanted to contribute to the war effort by creating paintings that depicted each one.

The artist struggled with how best to visualize the abstract concepts. “I juggled the ‘Four Freedoms’ around in my mind, reading a sentence here, a sentence there, trying to find a picture,” he later recalled. “But it was so high-blown. Somehow I just couldn’t get my mind around it.”

One night in bed, Rockwell was mulling over the proclamation, getting more discouraged as hours ticked by. “I suddenly remembered how [neighbor] Jim Edgerton had stood up in a town meeting and said something that everybody else disagreed with,” Rockwell said. “They had let him have his say. No one had shouted him down. I thought — that’s it. Freedom of Speech — a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want — a Thanksgiving dinner. I’ll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes … in terms everybody can understand.”

Excited and confident, Rockwell rolled up his sketches and boarded a train for Washington, D.C., to visit the government’s propaganda department, the Office of War Information, proposing that the illustrations be made into patriotic posters that could be sold to raise funds for the war effort. “I showed the Four Freedoms to the man in charge of posters,” Rockwell said, “but he wasn’t even interested.” On his way back to Vermont, the discouraged artist stopped in Philadelphia to discuss future projects with Post editor Ben Hibbs. In passing, Rockwell mentioned his Washington trip, explained what the series was about, and then showed him the sketches. Hibbs loved the idea, telling the artist, “Norman, you’ve got to do them for us. … Drop everything else, just do the Four Freedoms.”

Rockwell spent seven months painting the Four Freedoms, which were published in four consecutive issues of the Post, starting on February 20, 1943, accompanied by essays by four distinguished writers — Booth Tarkington, Will Durant, Carlos Bulosan, and Stephen Vincent Benet. The paintings were a phenomenal success, with the Post receiving 25,000 reprint requests. A few months later, the government changed its tune, and in May 1943, the Post and the U.S. Treasury Department launched a joint fundraising campaign, sending the paintings on a 16-city national tour. More than one million people attended the exhibition that raised an astounding $132 million.

Now hanging in the Norman Rockwell Museum, the iconic paintings capture the freedoms we enjoy as Americans and the cherished ideals that unite us — timeless reminders of what we have and what we have to lose.

Freedom of Speech: Rockwell started the first painting in the series at least four times. He initially depicted an entire town meeting full of people, with one man standing up in the center of the crowd talking, but later felt “there were too many people in the picture.” He altered the composition significantly, tightening the focus on the speaker, now positioned in front of a blackboard, as townspeople listened respectfully to the speaker’s words.

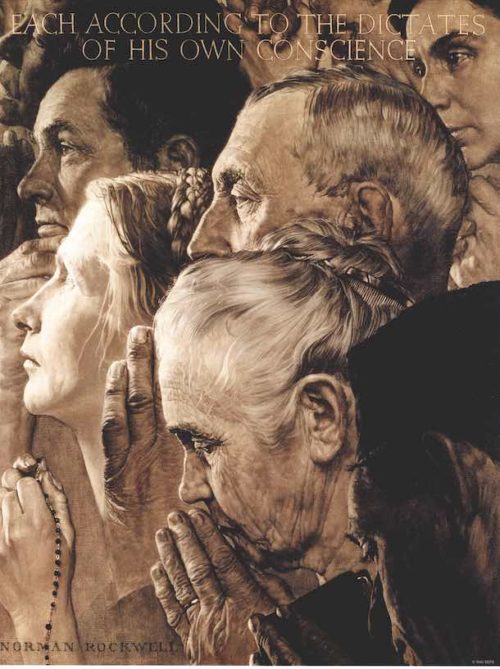

Freedom of Worship: The original painting was set in a barbershop, with patrons of various races and religions patiently waiting their turns. “I wanted it to make the statement that no man should be discriminated against regardless of his race or religion,” Rockwell said. Ultimately, Rockwell rejected that scene as ambiguous. Instead, his finished composition groups faces and hands — a mélange of different cultures — in prayerful contemplation, bearing the legend, “Each according to the dictates of his own conscience.”

Freedom from Want: One of Rockwell’s most famous and beloved works, Freedom from Want became an iconic representation of America’s quintessential national holiday, Thanksgiving. To create the scene, he grouped members of his own family and friends around a dinner table for a holiday meal. After two difficult paintings (Speech and Worship), this one came easy: “Mrs. Wheaton, our cook (and the woman holding the turkey), cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it.”

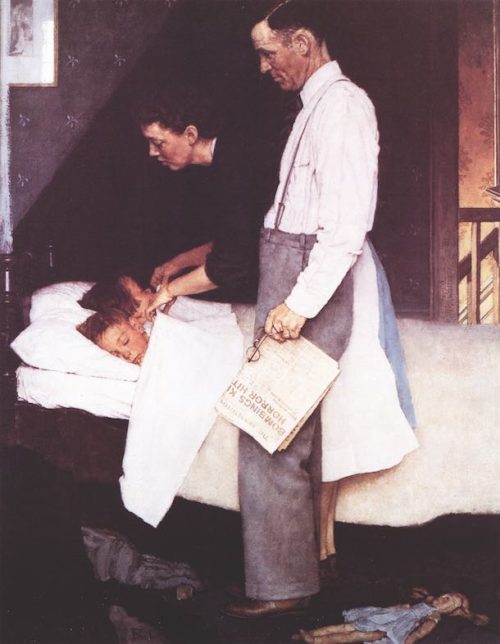

Freedom from Fear: The last in the series depicts children, oblivious to the mounting conflict in the world, resting safely in bed as their parents look on. The serenity of the scene is belied by the newspaper’s bold headline, “Bombing” — a reference the 1940–1941 blitz in London. Rockwell said the idea he hoped to convey was this: “Thank God we can put our children to bed with a feeling of security, knowing they will not be killed in the night.”

Rockwell’s Lasting Legacy

by Abigail Rockwell

We are living in chaotic and even alarming times, but here’s the tremendous gift: We are compelled to go within — so much outside of ourselves is beyond our control — to discover what our true values are — what is really important to us, for our families and our lives. Everything becomes clear in times of crisis. All of us are now urged to revisit the Four Freedoms and what they mean to us. Freedom of Speech (and the Press) is more relevant and vital than ever before; Freedom from Want — the polarity of the haves and the have-nots is starkly apparent and pressing; Freedom of Worship as everyone’s faith is being tested, judged, and at times viciously condemned; and Freedom from Fear haunts all of us as we attempt to gather greater strength, courage, and renewed purpose in the face of escalating troubles around the world.

The process of painting the Four Freedoms ushered in a new phase in my grandfather’s work; a greater sense of purpose, refined technique, and heightened storytelling began to inform his art from then on.

The great studio fire that occurred shortly after he completed Four Freedoms — a blaze that destroyed his entire studio and its contents, including the collection of his own work — forced him to immediately let go of the past and start all over again in the harsh light of an inestimable artistic and personal loss. But he embraced it, moved to a less isolated home on the West Arlington town green, and became very close with his neighbors — the Edgertons and the entire community in Vermont — which also greatly benefited his work and life.

Without his seven-month struggle in painting the Four Freedoms and the subsequent studio fire, the period of Norman Rockwell’s masterpieces in the late ’40s to mid-’50s simply would not have occurred.

To read the complete Four Freedoms essays, visit saturdayeveningpost.com/fourfreedoms.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Art of the Post: The Rockwell Cover that Led to a Marriage

Modern art critics have often looked down their noses at Norman Rockwell’s realistic style of painting, dismissing his painstaking details as unnecessary and old fashioned. But for at least one person, the details in Rockwell’s painting led to a life-altering experience.

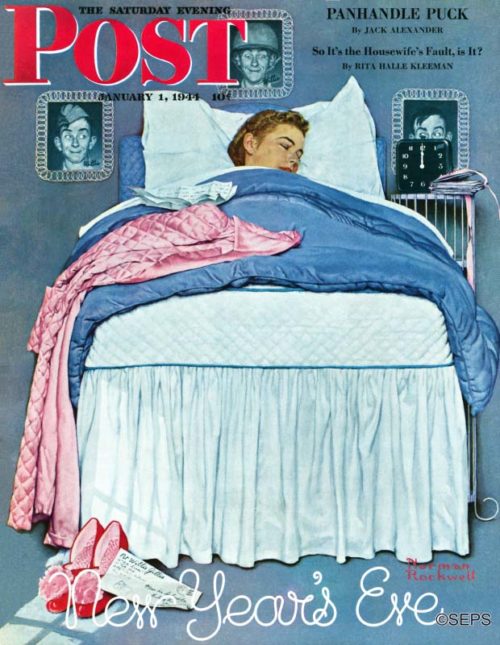

In this 1944 Post cover, Rockwell painted a pretty young girl asleep in bed at midnight on New Year’s Eve. Rather than go out partying, she dreams about her soldier boy overseas.

Rockwell literally selected the girl next door for his model. He asked his close friend and fellow illustrator, Mead Schaeffer, if Schaeffer’s sixteen-year-old daughter Lee would pose for the cover. Schaeffer lived just up the street from Rockwell in Vermont.

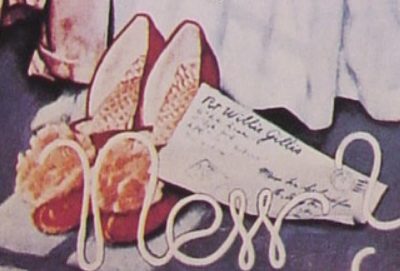

Ever the perfectionist, Rockwell also selected just the right details to tell his story. That clock on the bedside table shows us that it is midnight and the young girl is not out celebrating in those fancy party shoes. The photos of her boyfriend — none other than Rockwell’s favorite GI, Willie Gillis — on the wall tell us why. But do extra details such as the envelope on the floor really make any difference?

Rockwell was such a stickler for detail, when he painted that envelope he used Lee Schaeffer’s actual address. He assumed it would be too small and blurry to be legible when it was finally reproduced on the cover of the Post. The address was just one of the many details that Rockwell captured purely for his own satisfaction.

Unfortunately, Rockwell underestimated the resourcefulness of our young G.I.s. Soldiers were so smitten by the lovely Lee that they got out their magnifying glasses. Before long, letters started streaming in to Lee Schaeffer at home. Lee’s mother became quite upset with Rockwell for putting her daughter’s address on the cover of the Post. She made sure that all of Lee’s fan mail went unanswered.

But that’s not the end of the story. A few years later, a young veteran named Bob Goodfellow, recently back from serving in the U.S. Navy Reserve on Iwo Jima, saw the famous cover. Like others before him, he fell in love with the slumbering girl. But unlike other soldiers, Goodfellow had an advantage. His fraternity brother knew the Schaeffer family and happened to be dating Lee’s sister Patricia. Goodfellow kept pestering his fraternity brother to arrange an introduction, and finally his persistence paid off. The fraternity brother gave in and arranged a double date with Lee and Patricia in New York City. Goodfellow met Lee on a blind date on December 3, 1949. Goodfellow must have made a good first impression because he was able to wrangle an invitation to Mead Schaeffer’s New Year’s party. There, Lee introduced Goodfellow to her parents, he passed the test, and the courtship began.

Goodfellow and Lee Schaeffer were married on March 16, 1951, and they remain happily married in Vermont today. Next March will be their 67th anniversary. The famous Rockwell cover of the Post that started it all is framed and hanging on the wall above Goodfellow’s desk.

Many modern art critics have insisted that the tiny details in Rockwell’s paintings are pointless. They should keep their eyes and minds open. You can never tell where paying attention might lead.

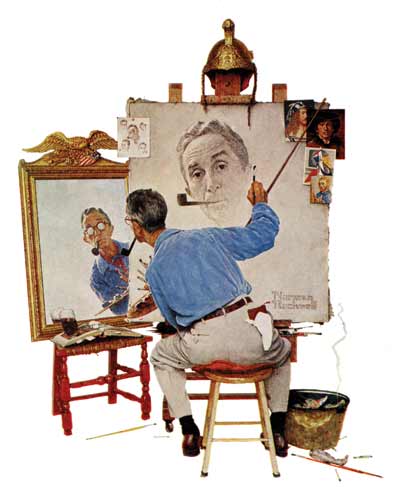

Rockwell Finally Appears as Himself in Triple Self-Portrait

© SEPS

In 1960, Norman Rockwell produced one of the most famous self-portraits in American art. A naturally modest man, he clearly had some reservations about making himself the subject of a cover. He’d put himself on covers before, but usually only as a cameo, never the central figure.

In describing this work, Rockwell explained why his glasses look opaque. “I had to show that my glasses were fogged, and that I couldn’t actually see what I looked like — a homely, lanky fellow — and therefore, I could stretch the truth just a bit and paint myself looking more suave and debonair than I actually am.”

As visual reinforcement of his intentions, at the top of the easel, Rockwell has included a reminder to himself not to be taken in by appearances. He bought this helmet in a Paris antique shop, thinking it was the headdress of an ancient Greek or Roman soldier. Carrying it back to his hotel, he stopped to watch a firefighter working to save a burning building and realized that all French firemen wore helmets identical to the one he’d just purchased.

For all Rockwell’s self-deprecation, the painting is regarded by many as a thoughtful portrait of the artist’s three selves: the painter, the observer, and the public person.

This article is featured in the November/December 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

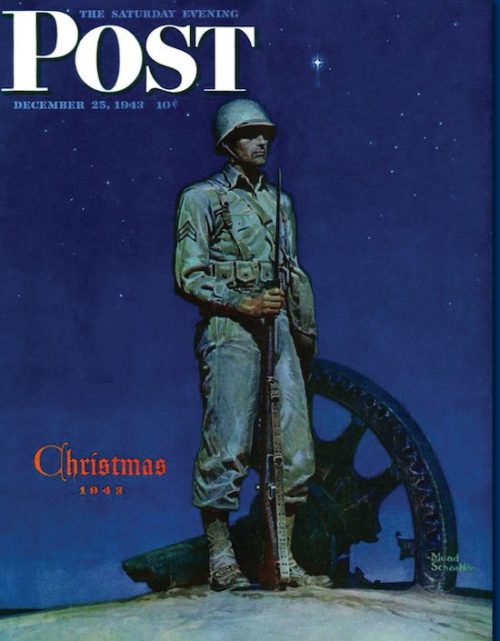

The Art of the Post: Rockwell Goes to War

During World War II, two Saturday Evening Post illustrators, Norman Rockwell and Mead Schaeffer, wanted to aid their country’s war effort. They were too old to enlist, and neither one was physically suited to be a fighter, but they felt they might be able to help with their art.

The two artists decided to paint patriotic pictures and offer them free to the Department of Defense for fundraising and enlistment campaigns. They worked hard developing their preliminary drawings; Rockwell decided to illustrate Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” while Schaeffer chose a series of military themes. When they finished mapping out their ideas, the two took the long train ride from their studios in Vermont to the U.S. Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. The illustrators excitedly showed their proposals but met a frosty reception.

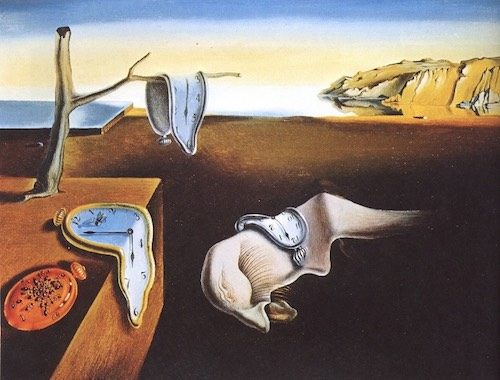

The Assistant Director of the Office was Archibald MacLeish, a famed poet, future Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, and proud intellectual who didn’t think much of illustration. Rockwell recalled being told, “The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.” MacLeish thought the military should use artists such as Salvador Dalí, Marc Chagall, and Stuart Davis to inspire the American public.

The Pentagon was not totally unsympathetic to Rockwell and Schaeffer. According to Rockwell’s autobiography, it offered them a consolation prize: “If you want to make a contribution to the war effort, you can do…pen-and-ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.”

Stung, the two illustrators took the long, depressing train ride home to Vermont. Schaeffer’s family recalls that when Schaeffer’s wife learned of the rejection, she spoke up: “To heck with the Army, why don’t you offer your pictures to the Post instead?”

The illustrators turned around and took the train back down to the Post’s offices in Philadelphia. There, editors reviewed the preliminary drawings and agreed to run Rockwell’s paintings as internal illustrations, followed by Schaeffer’s paintings in later issues.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms quickly became a national phenomenon. The Post received 60,000 letters about them. As editor Ben Hibbs later wrote:

The results astonished us all. … Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications. Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in this country but all over the world. [Rockwell’s] four pictures quickly became the best known and most appreciated paintings of that era. They appeared right at a time when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautifully.

It began to occur to government officials that they might have made a mistake rejecting the paintings. Belatedly, they tried to jump on the bandwagon. With Rockwell’s permission, the Treasury Department took the Four Freedoms on a tour of the nation as the centerpiece of a Post art show to sell war bonds. The paintings were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

The illustrations proved far more effective than anything else the government had planned. The Pentagon even sent a film crew to Vermont to stage a documentary about the illustrations, implying (falsely) that Rockwell and Schaeffer had been working at the behest of the government all along.

As for MacLeish, he did not last long in his job. Rarely has a misguided act of cultural arrogance been so promptly, resoundingly, and satisfyingly refuted.

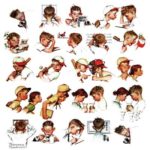

Psst! Wanna Hear a Secret?

Have you heard the story behind Rockwell’s cover The Gossips? Some say the painting was Rockwell’s revenge on a woman in Arlington, Vermont, who’d spread an ugly rumor about him. He re-created the life of the rumor, beginning with an elderly woman whispering about Rockwell to a neighbor. From there the tale takes wing, speeding through town from one eager gossip to the next, until it comes back to Rockwell himself, who confronts the rumor’s originator in the bottom right.

The faces are so carefully delineated you can almost hear the sound of their voices passing along the story in tones of shock or malevolent glee. But when the work was completed, Rockwell worried he had gone too far in caricaturing the neighbors he’d used as models. He even went so far as to ask the Post to assure readers that the people of his hometown were much better looking in life than the way he portrayed them.

Was the painting truly an act of revenge? It seems to have been regarded as such. When The Gossips appeared on the Post’s cover, what we heard is that the woman never spoke to Rockwell again. In fact, some say she left town. (Of course, this has to stay just between us.)

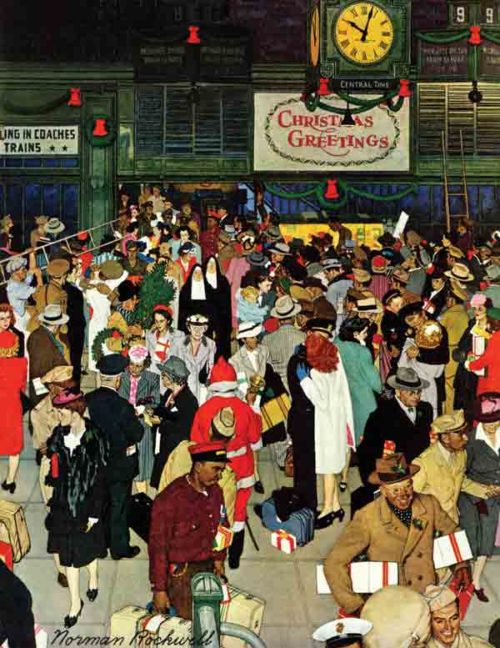

Crowd-sourced: Norman Rockwell’s Christmas at Chicago Union Station

Union Train Station, Chicago, Christmas contains many of Norman Rockwell’s favorite themes — homecoming, reunions, sweethearts, and Christmas — and he wanted to get it just right.

In the planning phase, Rockwell scouted several train locales before choosing the Chicago and Northwestern railroad station. Always concerned with accuracy, the artist asked railroad officials how they planned to decorate for the holidays. They hadn’t decided yet, as Christmas was months away, so they told Rockwell to paint it as he wished and they’d decorate the station to match.

Among the shoppers, you’ll notice some servicemen in the crowd waiting to be reunited with their families. After photographing real servicemen for these scenes, Rockwell recruited women to pose kissing some of the soldiers. The red-haired woman in the foreground kissing an officer was discovered as she hurried through the station. Afterward, when Rockwell thanked her for posing for the kiss, she replied, “Not at all; sorry it wasn’t a time exposure.” Look closely and you’ll see Rockwell himself in the picture; he’s the man waving a folded paper in the upper right.

Sign on the Dotted Line

Norman Rockwell

June 11, 1955

Always a stickler for authenticity, Rockwell asked an engaged couple to pose for The Marriage License. He also asked a former town clerk, Jason C. Braman, to pose as the city official. Rockwell knew the old man was still mourning his wife, who’d died just a few months earlier, and thought sitting for the painting might lift Braman’s spirits. Rockwell’s plan worked. When the issue was published and neighbors asked if he was the man on the Post cover, Braman delightedly offered to autograph their copy.

This cover displays Rockwell’s genius for capturing the drama in everyday scenes. He contrasts the dark municipal office and its shelves of dusty books with the woman’s sunny dress and the promise of bright sunlight coming in the open window.

And he used the solitary old clerk to emphasize the hopefulness of the young couple. The effect was so ideal that Rockwell once pointed to the handsome bridegroom and said, “That is what I would have liked to look like if I had had the opportunity.”

How a Classified Ad Brought Rockwell Two Black Eyes

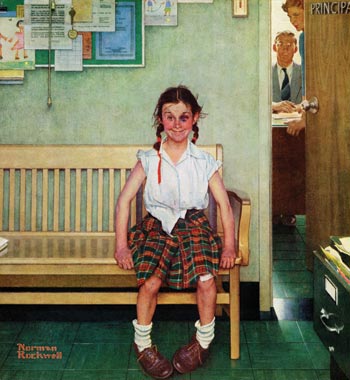

Portraying a boy with a black eye was commonplace enough. Here, Rockwell gives the schoolyard dust-up a then-modern twist by painting a girl combatant who, judging by her grin, was the victor. But as he worked on the cover illustration, Rockwell found himself in a jam because his model was not, in fact, injured. And painting a realistic shiner was challenging, since a truly “black” eye contains multiple colors, none of them black.

Rockwell halted work to visit several hospitals but found no patients in the right condition. An obliging photographer ran an ad in the local paper, announcing a search for a model with a black eye. This created another diversion as the media caught wind of the story, and soon Rockwell was getting offers from across the country. But then, a bit of luck came Rockwell’s way when Tommy Forsberg of Worcester, Massachusetts, fell down the stairs and blackened both his eyes. His father drove him to Rockwell’s studio, where his injury would be immortalized, albeit on a young girl’s face.

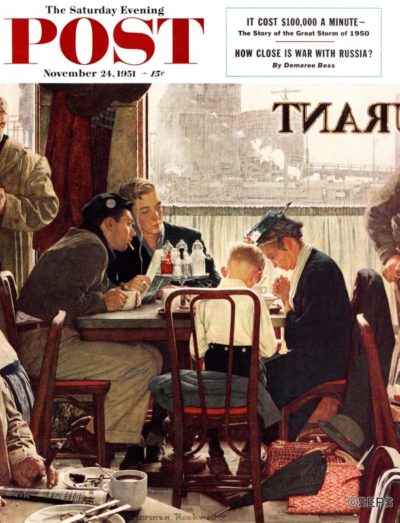

Rockwell Rising

November 24, 1951

© SEPS

Throughout history, most great artists have been storytellers, whether in paintings scratched out on the walls of caves to chronicle the hunt or, later, in lush canvases and intricate frescoes to interpret scenes from the Bible or to record great battles. Norman Rockwell comes from just such a tradition.

Ordinary people doing ordinary things were his subjects for the most part. “The commonplaces of America are to me the richest subjects in art,” Rockwell wrote in 1936. “Boys batting flies on vacant lots; little girls playing jacks on the front steps; old men plodding home at twilight, umbrellas in hand — all of these things arouse feeling in me. Commonplaces never become tiresome. It is we who become tired when we cease to be curious and appreciative.”

The public adored Rockwell from the start, says Laurie Norton Moffatt, director and CEO of the Norman Rockwell Museum. If, in the postwar world of abstract expressionism, folks stared in befuddlement at Ad Reinhardt’s black-on-black canvases or Jackson Pollock’s splatter paintings, Rockwell’s work was a breath of fresh air.

“We know from the fan mail received at The Saturday Evening Post that people were extraordinarily attentive to his work, even to the point of catching him out on details if something was a little off about the picture,” she says. “But most of the letters were accolades of how much they were moved, or touched, by a particular picture.”

Rockwell famously put in long hours, heading off to his studio seven days a week, holidays included. Joseph Csatari, who served for eight years as art director for Rockwell’s Boy Scout paintings, recalls that the artist needed a daily intervention just to pry him away from his easel: “Every day at 11 o’clock, Rockwell’s wife Mary would knock on the studio door to remind him to take a break. ‘If I didn’t,’ she would say, ‘he’d work through dinner.’”

Rockwell’s total production was staggering. In his lifetime, he painted nearly 4,000 images, including 800 magazine covers — 322 for this magazine alone — and ad campaigns for more than 150 companies.

Today his paintings are more popular than ever, commanding eight-figure fees from collectors and drawing crowds to museums. Among his better-known fans are film directors George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Both speak reverently of the artist’s storytelling skills, likening his paintings to film. “He was able to sum up the story and … understand who the people were, what their motives were, everything in one little frame,” Lucas said in an interview. “I think he’s left a legacy that’ll never be forgotten.”

But for all his popularity, and, in fact, because of it, Rockwell was for most of his lifetime a flop in the eyes of the art world. “His success was his failure,” wrote Arthur Danto in a 1986 review in The New York Times, adding, “He possessed a demonic gift for likenesses, but an appalling lack of taste.”

As Moffatt tells it, he was approached by young art students during a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949 and asked by one, “You’re Norman Rockwell, right?” Touched with pride at being recognized, he was stung by the comment, “My art professor says you stink!”

Rockwell was well aware that he was out of step with the elites of the art world. “I have always wanted everybody to like my work,” he writes in his autobiography. “I could never be satisfied with just the approval of the critics (and boy, I’ve certainly had to be satisfied without it).”

Understanding the criticism Rockwell endured for much of his career requires some perspective about the history of American art, which went through seismic upheavals during his lifetime. Early in the 20th century, classically trained illustrators were national celebrities and trendsetters — admired and emulated the way sports figures and actors are today. “When you look at the 1920s, illustrators like John Held Jr., who was setting flapper fashions, or his forebears Charles Dana Gibson, who created the Gibson Girl, or J.C. Leyendecker, whose ads for Arrow shirts defined the styles and the fashions of the day — these illustrators defined how people dressed and acted, and even shaped what they should aspire to be,” Moffatt says.

But change was coming. Art historians point to the 1913 Armory show in New York as a critical turning point. Today, it’s hard to imagine the uproar the show caused. Nearly 90,000 people came to see the exhibition, which featured then-unknown-in-America artists such as Georges Braque, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Pablo Picasso, and many others. The abstraction — Cubism! Fauvism! — was a pie in the face of the classical tradition, and many viewers were outraged.

“For the very first time, American artists were introduced to the breaking down of form, of color, anatomy not being presented realistically,” Moffatt says. “American artists realized they had a choice. Many went to Europe to study these new styles, and you began to have this division. Artists could stay in the narrative tradition, painting pictures that are about a recognizable subject — pictures that involve people or landscape — or you could choose to go into these more abstracted forms of art.”

Rockwell, born in 1894, also caught the modern art fever, if briefly. At 29, already an established artist for the Post, he traveled to Paris to study the latest fads. Right from the beginning, it was not a perfect fit, as he writes in his autobiography. But, on his return, he attempted an abstract cover for the Post that was quickly and mercifully rejected. “I don’t know much about this modern art, but I know it’s not your kind of art,” the famously taciturn editor George Horace Lorimer told him. “Your kind is what you’ve been doing all along.”

April 24, 1926

© SEPS

Rockwell did revert to form, of course, but throughout his life, he was occasionally troubled that he was an anomaly among the leading artists of his day. “I think any artist who is a creative genius will go through periods of self-doubt,” Moffatt says. “And what comes through in Norman Rockwell’s own autobiography, where he writes about these episodes of depression, is how he always came through them with a burst of creativity where he was painting his absolute best. It’s a measure of his great strength and of his talent and genius.”

That genius must have been evident immediately to Lorimer, who, 100 years ago, bought two of the unknown young artist’s works at first sight. “Even in those early works, Rockwell was already evidencing the deep sense of observation, that keen sense of just how people interact,” Moffatt says. “If you look at the Boy with Baby Carriage, at first it’s all about the humor — the jeering friends running off to play ball while the older brother is stuck babysitting his sister. But as you look more closely, you’re drawn to the detail: the baby bottle in his breast pocket, the bowler hat clipped onto his lapel. I think it is that attention to detail, the little things that spark the humor, and that always take you a little deeper into the picture, that is the hallmark of his great talent.

“So you have an editor who is very skilled and who knows what he likes, who knows what will work for the Post, and he gave Rockwell a tremendous chance, and of course Rockwell never looked back, and he never let Lorimer down.” (For the full story of Rockwell’s thrilling initial encounter with the Post, see “A Fruitful Relationship,” by granddaughter Abigail Rockwell.)

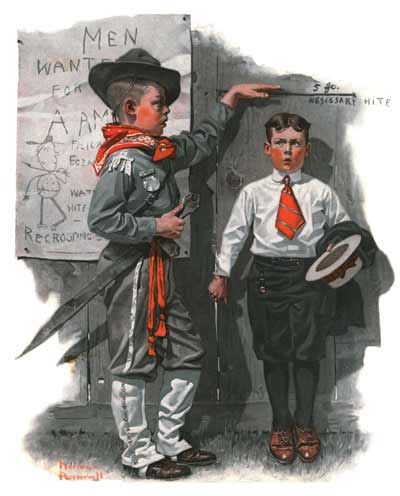

June 16, 1917

© SEPS

There is an additional layer of meaning when you consider the historical backdrop of many of Rockwell’s works. Citing Recruiting Officer, from the June 16, 1917, cover (above), Moffatt notes the obvious storyline — two kids are play-acting as soldiers out in the yard, and one kid isn’t measuring up: “He’s not tall enough to be recruited as a soldier, and the other young man has a wooden sword, and he has this bandana on, and he’s in his scout uniform. What one would have known at that time is that World War I was going on, so Rockwell is incorporating the larger narrative of world events into this narrowly focused microcosm of two kids in the backyard playing. There are so many things to talk about in these pictures beyond the first sort of joke that might stand out to us.”

But, always, the warmth shines through. “It has to be kept in mind that he’s doing all these paintings through the influenza epidemic, through the Great Depression, through the worst wars in the history of the world,” says Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough. “Yet he maintains a positive theme. Rockwell is like the minister who gives an encouraging sermon every week, and keeps the faith in the American ideal.”

McCullough has a unique perspective on Rockwell, having spent a day with the artist when he was still a student at Yale and contemplating becoming an artist himself.

McCullough painted an illustration that was used for the cover of the program of the Yale-Dartmouth football game. “I was a great admirer of Rockwell, and the drawing — a father and son attending a football game — was very much in the Rockwell spirit.”

A classmate of McCullough’s who lived in the Berkshires near Rockwell arranged for the two to meet. “Rockwell could not have been nicer,” McCullough recalls. “I went up to meet him at his studio, above a store on the main street of the town. He was like a character from his paintings — a small, frail, bent-over man, physically not impressive at all, but his spirit was strong. There was no sense that I was in the presence of some great artistic genius. He struck me as a man who didn’t have much time for ego. He was too busy having the best of life through his work.”

McCullough spent the better part of the day with Rockwell. He watched him paint. Then they went to Rockwell’s home and had lunch, and Rockwell was quite encouraging about the young man’s artwork. “It could not have been a more memorable experience. He was one of my heroes,” McCullough says.

© SEPS

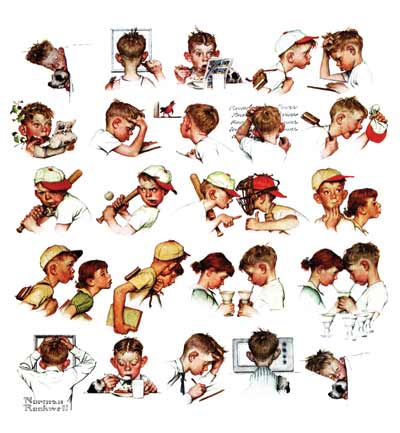

Today, the richness and depth — and yes, the earnest good nature — of Rockwell’s artwork is finally appreciated. (In 2014, Rockwell’s Saying Grace sold for $46 million, setting a record for his work.) But through much of the 20th century, while Rockwell was paid well, the paintings themselves had little or no value — they were merely the medium for delivering his pictures to the printed page. As an example, when the artist donated his canvas of Day in the Life of a Boy to the town’s Community Club for its annual raffle, the work raised a grand total of 50 cents.

Another anecdote that reflects Rockwell’s modesty about his own canvases comes from Csatari: “On one of my early visits to Stockbridge, I took a walk over to the Old Corner House museum to see some of Norman’s paintings while he took his nap. At the museum, I entered a room that held his Four Freedoms. I remember feeling as if I were in church. But in an instant, the reverence was broken. I saw painters on ladders slapping white latex on the ceiling and spattering the paintings below. I was stunned. I hurried back to the studio to tell Norman, who was back at his easel. He took a thoughtful puff of his pipe, then smiled and said, ‘Gee, Joe, maybe they’ll improve ’em.’”

How did Rockwell’s reputation rebound? As early as 1946, the renowned author of art instruction books Arthur Guptill published Norman Rockwell, Illustrator, a book that celebrated his work, notes Moffatt. But it wasn’t until 1968 that there was any serious interest in his original canvases. Rockwell was caught off guard when New York gallery owner Bernie Danenberg called him one afternoon in July 1968 to suggest mounting a show.

“I’m sorry,” Rockwell said, “but I think you have the wrong artist.”

Danenberg insisted he was not mistaken and drove up to Stockbridge the next day with his gallery manager. Arriving in town, they proceeded directly to his studio. Treasures abounded. Danenberg instantly fell for Lift Up Thine Eyes, a painting that depicted city people rushing past a beautiful old Manhattan church, oblivious to its beauty. The art dealer offered to buy the painting on the spot for $2,500. Rockwell at first refused to accept any money for the painting, saying, “I got paid for it once. I don’t need to be paid again.”

Danenberg persisted, and Rockwell ultimately agreed to sell the painting. He also agreed to schedule an exhibition for October of the same year. As art blogger Ann Restak writes, the exhibition marked the first time that Rockwell sold an original illustration as artwork.

There was a second gallery exhibition in 1972 and another traveling exhibition organized by the Brooklyn Museum. So one could regard the early ’70s as something of a turning point for Rockwell. “He went from being an artist on the cover of magazines to an artist who had his paintings on the walls of museums and galleries,” Moffatt says.

Collectors slowly began to take notice. “We see, around 1978, the very first auctions of Rockwell’s work in the major auction houses, such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s,” Moffatt says. “But it was still rare for American illustrators to be sold at art auctions. Honestly, it wasn’t greatly admired by the auctioneer. It would be shown on the back page of the auction catalogue, and sold for very little.”

It wasn’t until 1999, when the Norman Rockwell Museum and the High Museum of Art produced a large-scale exhibition titled Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, that opinion leaders in the insular art world finally came around. The show traveled to seven American cities, ending in New York at the Guggenheim Museum. Now, writes Restak, his work was finally legitimized “in the hallowed halls of a world-class art institution.”

It didn’t hurt that the exhibition catalogue included essays by such authorities as Moffatt; Ned Rifkin, director of the High Museum of Art; and Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In his essay for the catalogue, Hoving argues that critics must take another look at Rockwell and “place him in his authentic position in art.” He calls Rockwell “one of the most successful visual mass communicators of the century” and points out that “art history, for snobbish reasons, has always been suspicious of artists considered populizers.”

© SEPS.

Admiration for Rockwell has only grown as his paintings are exhibited with more frequency. “The experience of viewing an original Rockwell is very profound,” Moffatt says.

“The more people see Rockwell’s work in the original format, the more they are just wowed by what an extraordinary artist he was. You just can’t deny the artistry, the exquisite detail, and, of course, his keen observation of human nature.”

“He had a tremendous respect for the virtues of mankind,” Spielberg has said. “And there was a real sense of community, of family, and especially of nation.”

“Above all, Norman Rockwell was an extraordinarily kind person, and he genuinely loved people,” Moffatt says. “There’s so much anger in our nation today — and a certain amount of coarseness in the culture overall. But when people look at Rockwell’s work, not only do they respect it and like it, I think maybe they long for those qualities to be present once again. Not to go back in time, but to bring forward some of these guiding principles of how society could be.”

How will Rockwell be regarded 100 years from now? “Unabashedly I would say we’ll remember him the way we remember Rembrandt and Michelangelo,” Moffatt says. “Rockwell’s work will be held up and admired, and hold its own, alongside the greatest painters in the world.”

Click images to enlarge:

June 16, 1917

© SEPS

April 24, 1926

© SEPS

August 13, 1927

© SEPS

March 9, 1929

© SEPS

September 26, 1936

© SEPS

September 2, 1939

© SEPS

February 20, 1943

© SEPS

February 27, 1943

© SEPS

March 6, 1943

© SEPS

March 13, 1943

© SEPS

November 24, 1951

© SEPS

May 24, 1952

© SEPS

A Rockwell Mother’s Day

The American holiday Mother’s Day came about chiefly due to the efforts of one woman, Anna Jarvis. After the death of her mother in 1905, she conceived of a day honoring all mothers. The first Mother’s Day celebration occurred in 1908. In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed a measure establishing the second Sunday in May as Mother’s Day.

Throughout the 20th century, mothers have taken center stage on our covers and in our magazine. As a special tribute to moms everywhere, we present this collection of Norman Rockwell covers where moms and grandmas play a starring role:

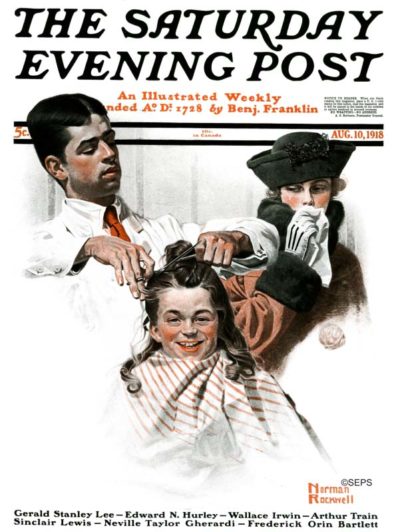

August 10, 1918

This momma’s boy is absolutely thrilled to be losing his luxurious locks, but his mother mourns more than just the loss of those curls: her little boy is growing up.

October 21, 1933

When this cover was published in 1933, a mother in Rockwell’s New Rochelle neighborhood thought the girl in pigtails looked just like her daughter — so much so that she framed the magazine to hang on her wall. Years later, Rockwell found out and gave the nostalgic mother the original oil painting.

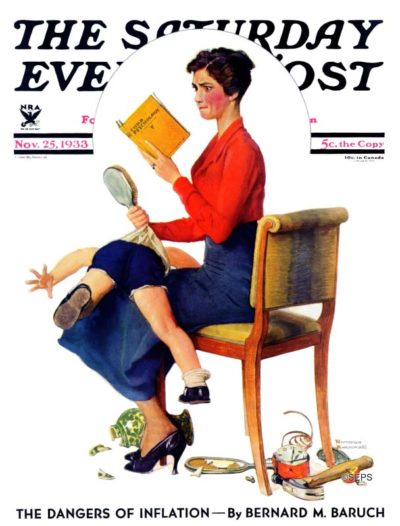

November 25, 1933

Resisting the urge to wallop her child for researching the aftereffects of a hammer on household objects, this mother jumps to a psychology book for help. The scene, we’re told, may have been inspired by actual events in the Rockwell household. When this 1933 illustration was published, Norman and Mary Rockwell’s oldest son, Jerry, had just reached the “terrible twos.”

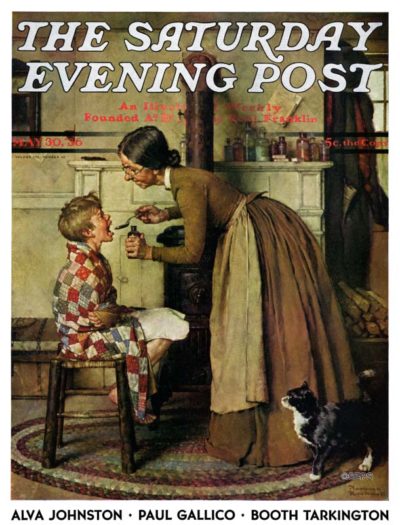

May 30, 1936

Tom Sawyer’s mothering Aunt Polly and her force-feeding “quack cure-alls” prompted Rockwell to create this cover in 1936. The image also appeared in a reprint of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which Rockwell illustrated for Heritage Press that same year.

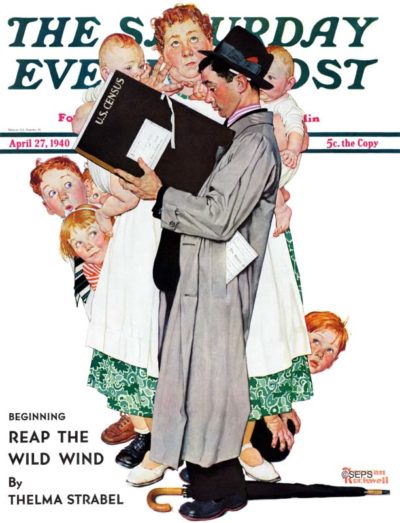

April 27, 1940

Remembering kids’ birth dates can be tough, especially if you can’t recall just how many kids you have. While this mom attempts to count off those birth dates, a passel of kids peeks out from behind her to catch a glimpse of the strange man who’s writing it all down in a large black book. The scene, which takes place in California according to the census book, graced the Post cover in 1940, when the bureau was conducting its 16th census of the United States.

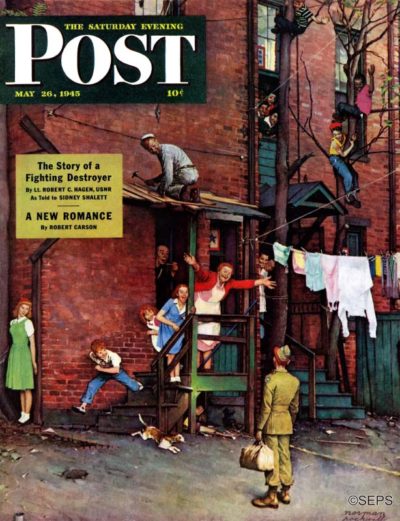

May 26, 1945

This 1945 painting of a young GI returning to the open arms of his mother is one of Rockwell’s most celebrated. The idea for it came to Rockwell after he read a series of 1944 Post articles written by Charles “Commando” Kelly and Pete Martin.

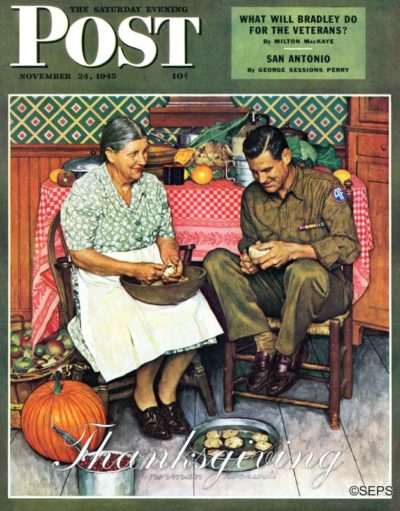

November 24, 1945

During World War II, Rockwell illustrations like this one boosted the spirit of America, especially in mothers of sons fighting overseas. Perhaps what made this one all the more touching for Post readers was knowing that the models in this homespun scene were an actual mother and son pair — Alex Hagelberg and her son, Dick, a bombardier who flew 65 missions over Germany.

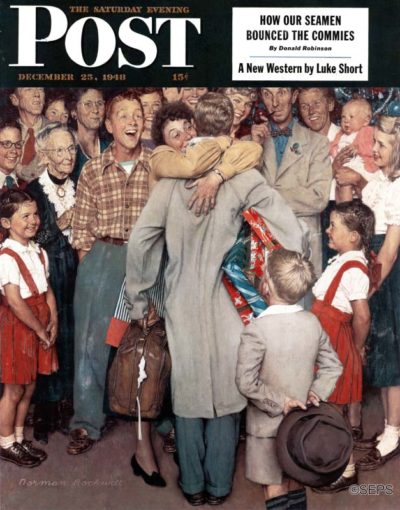

December 25, 1948

Another happy scene featuring a true-to-life family. Mother Mary Rockwell hugs and welcomes oldest son, Jerry, home. To her right, the boy in plaid is middle son, Tommy, and to her far right, in glasses, is youngest son, Peter. Artist Rockwell stands at her left. And between the two younger boys stands another famous painter — and mother of five — Grandma Moses.

November 24, 1951

One of the best-known of Rockwell’s works, this painting of a grandmother and grandson praying in a diner was voted the Post readers’ favorite cover in 1955. Though May Walker, the woman who posed as grandmother in this painting, died just five days before the issue appeared on newsstands, she did get to see the painting completed. People who knew Walker well told the Post that posing for this cover was one of the most enjoyable moments in her life.

A Tale of Two Streets

You may not see it, but there’s a 17th-century Dutch painting within the 1953 cover, Walking to Church. Rockwell depicts a family, dressed in their Sunday best, on a city street before the neighbors awaken to take in their milk and newspapers. The scene may seem quiet, but Rockwell showed us, with a line of birds rising in sudden flight from the steeple, that the church bells have begun ringing.

Rockwell’s cover reflected his admiration of View of Houses in Delft, a 1658 painting by Johannes Vermeer that showed a quiet street in the Dutch artist’s hometown. Not only did Rockwell copy Vermeer’s theme, but he also tried to replicate its 21-by-17-inch size. Rockwell’s painting is tiny, for him — just 19 by 25 inches. He wanted to paint it the same size as the Vermeer original, but he couldn’t get a canvas small enough. “Couldn’t paint it better than Vermeer,” he said. “So I painted it bigger.”

Editor’s note: This article has been corrected from the version which appeared in the March/April issue. The article in print was published under the wrong author’s name and stated that Rockwell’s painting was 19 by 18 inches.

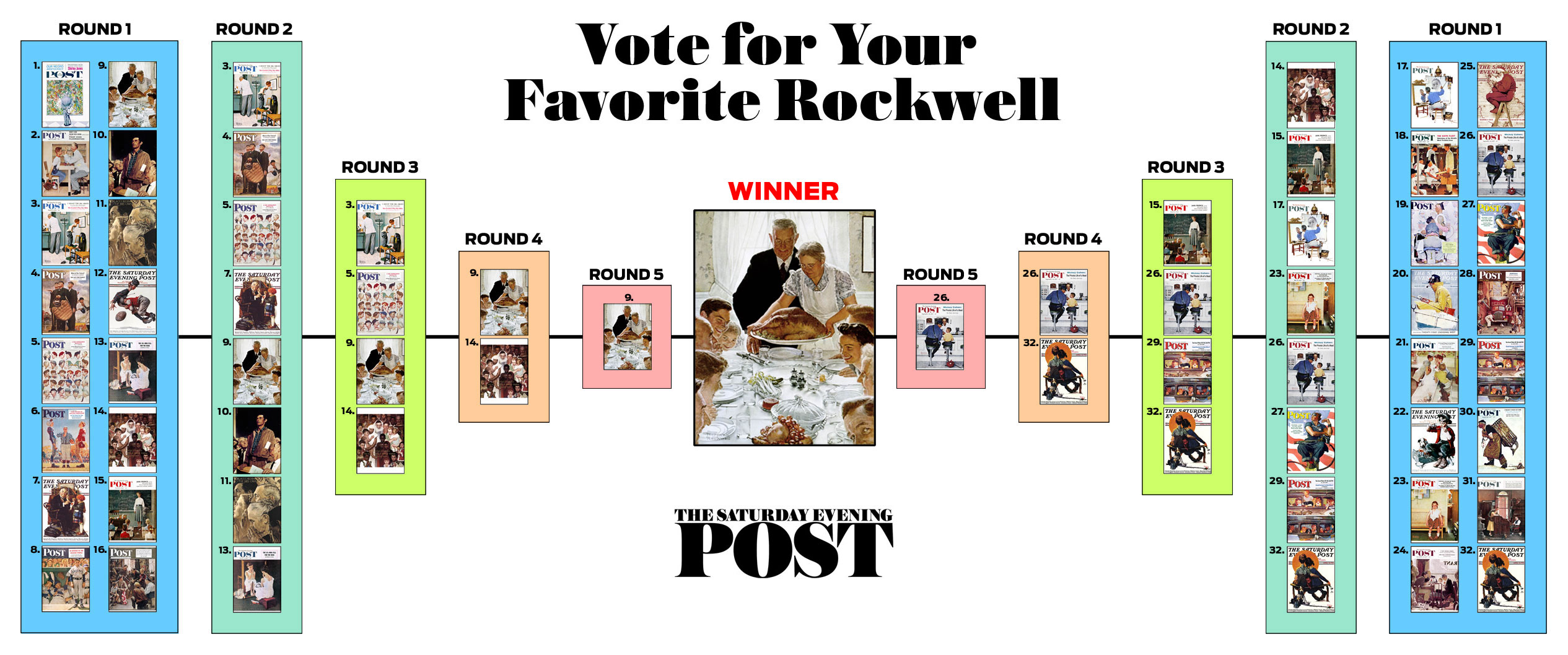

Winner Announced: Vote for Your Favorite Rockwell

Thanks for playing Rockwell March! The U.S. saw Norman Rockwell’s art on The Saturday Evening Post cover for the first time on May 20, 1916 — almost 100 years ago. To celebrate the upcoming anniversary, we shared 32 of his iconic illustrations on our Rockwell bracket — and asked you to vote for your favorite.

We gathered votes from Facebook, Pinterest, and our website. It was a tough, five-week-long battle, and in the end, Rockwell’s Freedom from Want came out on top! To see the winner close up, just click on the bracket below or scroll down to view each Rockwell contender individually.

Or scroll down to view each image individually.

Click the numbers below to view the Rockwell contenders up close:

January 13,1962

May 19,1956

March 15,1958

April 23,1949

March 6,1948

October 21,1950

March 9,1929

September 4, 1948

March 6,1943

February 21,1943

February 27,1943)

November 21,1925

March 6,1954)

April 1,1961)

March 17,1956)

October 13,1945)

February 13,1960)

March 2,1957

March 4,1944

April 29,1939

August 22,1953

March 10,1923

May 23,1953

November 24,1951

December 16,1939

September 20,1958

May 29,1943

July 9,1949

August 30,1947

August 20,1955

June 11, 1955

April 24,1926

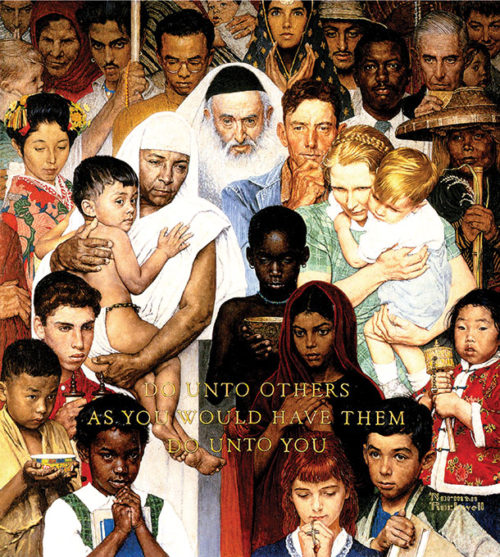

Something Serious

For Norman Rockwell, the 1960s marked a period of change. The mood of the country was shifting. The rising popularity of television in American homes fed a culture fascinated with celebrity. Catering to popular taste, many magazines began using photographic covers (frequently portraits) in place of illustration. While he would hold his position as the Post’s premier illustrator for a few more years, Rockwell could see the writing on the wall. At the same time, on a personal level, Rockwell was still mourning his wife, Mary, who died suddenly in August 1959.

During this period, the artist began to explore social issues. “Most of the time, I try to entertain with my Post covers,” Rockwell said. “Once in a while I get an uncontrollable urge to say something serious.”

In the summer of 1960, inspired by the idea that the Golden Rule was a universal principle threading through all religions, Rockwell decided to capture the concept on canvas.

After preliminary sketches, he remembered an earlier piece, United Nations, that had never been completed. He found the unfinished 10-foot-long charcoal in the cellar and hauled it upstairs to his studio. “I had tried to depict all the peoples of the world gathered together,” Rockwell said. “That was just what I wanted to express about the Golden Rule.”

Some portraits were repainted from the original charcoal. Others were created afresh, using neighbors as models. The rabbi (center) was Stockbridge’s retired postmaster (a Catholic in real life); and Rockwell’s late wife, Mary, appears to his right holding the grandchild she never saw.

The work appeared on the April 1, 1961, cover of the Post. Reader response was overwhelmingly positive.

As a testament to the power of the image, a mosaic based on the painting was installed at the United Nations Headquarters in 1985. It was rededicated following its restoration in 2014.

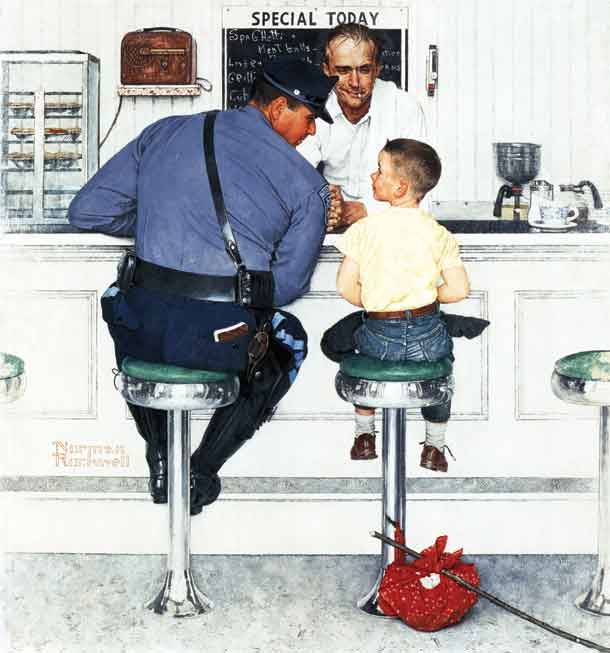

Protect and Serve

1958 © SEPS

Rockwell’s famous painting The Runaway depicts a child literally on a pedestal–well, barstool–surrounded by a protective and understanding community.

The setting is pristine; this is no ordinary diner. It’s the Platonic ideal of a diner, where the floor is immaculate, the counter gleams, and even the waiter’s clothing and towel are unsullied.

The only prop that suggests a disturbance is the wannabe hobo’s stick and handkerchief.

Normally a scene featuring a runaway child evokes anxiety. Instead, Rockwell’s painting radiates comfort and safety in the form of a triangle of protection surrounding the boy. To the left is the fatherly state-police officer, at the top is the counterman, and to the right is an empty coffee cup, suggesting another good Samaritan had been sitting there not long ago. Perhaps the anonymous diner made the initial call to police and then stayed with the boy until the officer’s arrival. The complete narrative depicts a cocoon-like community taking shifts to watch over a child in trouble.

In the painting, Rockwell portrayed an idyllic version of small-town America. In his sweet, safe universe, no child is ever in danger and no task is more pressing for an officer of the law than to spend a morning with a young runaway. After appearing on the September 20, 1958, cover of the Post, The Runaway began to grace the walls of countless diners and police stations throughout the country.

Fun fact: The Runaway was staged in a Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Rockwell later removed all traces of the chain restaurant in favor of a simple blackboard listing the daily specials often found in country diners “to suggest the kid had gotten a little further out of town.”

Beyond the Canvas: Rockwell’s April Fools’ brings laughter in a serious time

Norman Rockwell once said, “I showed the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.” Most of Rockwell’s covers are subtle opportunities to stop and look at the innocent, decent normalcy of American life. On three April Fools’ Days throughout the 1940s, Rockwell took a chance showing a surreal America no one knew, and he certainly made us notice.

After spending six months working on the serious Four Freedoms paintings, the ideas for which came from a speech by President Roosevelt, the April Fools’ covers were a welcome moment for Rockwell to take a step back from war and celebrate joyous laughter.

The covers turned seemingly innocent depictions of American life upside-down with hundreds of topsy-turvy injections of laughable absurdity. The first of the paintings appeared on April 3, 1943; the second on March 31, 1945; and the final April Fools’ Day cover on April 3, 1948. The scenes are simple Rockwell “Americana”: an elderly couple playing chess, a man fishing while leaning against a tree, and a girl shopping for a doll – all comically, nonsensically twisted.

American sensibilities had become more serious with the onset of World War II. Rockwell’s former models – children at play, in a store, at the doctor’s office – had grown into young men and women who were asked to serve their country. Although Rockwell would later return to paintings of children, everyday lives were turned upside-down by this new reality. Small-town simplicity had been traded for the construction of war machines, rations and collected supplies, and various means of an entire nation aiding the war effort.

Seeing the April Fools’ covers from the newsstand, or as they arrived in the mail, provided just as much fun for the viewership as Rockwell had taken in designing the illustrations. People could find each and every absurdity on their own or with a group, pointing out the various April Fools’ Day quirks and gaffes. They worked well as clever talking points to bring individuals, families, communities, and the nation together, coaxing them to pause, to put aside the feelings of seriousness and frustration that consumed the country.

The covers worked so well that by the time the third was published, finding the jokes in Rockwell’s April Fools’ Day art became an exciting game Post readers eagerly awaited. To this day, these three covers mesmerize viewers and bring a quick bout of laughter. See how many April Fools’ jokes you can spot and check your answers in the image below!

See answers to all of Rockwell’s April Fools’ covers here.