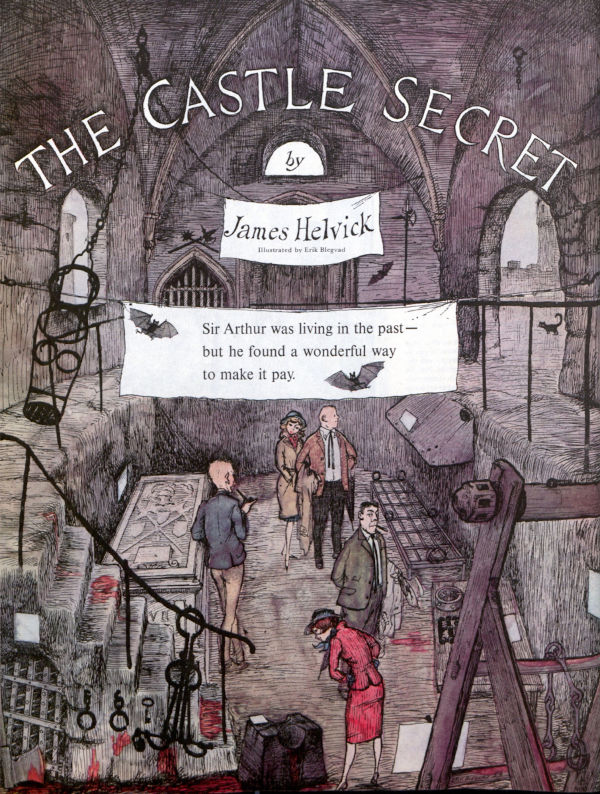

“The Castle Secret” by James Helvick

Claud Cockburn first received acclaim for his work as a journalist in England during the 1930s. He became most famous, however, for his affiliation with the British Communist Party during the Cold War. To avoid unwanted press, Cockburn began writing under the pseudonym James Helvick. He used the name to publish a number of works, including his 1951 novel Beat the Devil and the following story printed in the Post.

Published on October 17, 1959

A couple of ounces of pure, unblended English rain slid off the extended leaves of a wizened oak tree and struck Francis Manning just above the back of his collar.

“To think,” he said, “that that tree has been waiting to do that to me since the time of William the Conqueror.”

Nancy Manning said, “Hush, you’ll disturb the game.”

Francis Manning said, “Did you say game?” He looked at his wife sternly, but she continued to focus on the cricketers. Her expression was one of reverent attention. She was thinking about Sir Arthur Ludd.

Francis thought about him, too, with mingled awe, resentment and censure. He was irritably aware that it was this Ludd who, by remote control, had guided them and their daughter Francesca to the position in which they now found themselves — that is to say, England, inside a ruin, beside a lawn, on a bench, watching a cricket match.

During one of those regularly recurrent pauses — between what are called “overs” — which, as in Oriental music, are the very essence of cricket, Francis Manning said: “I yield to no man in my respect for Sir Arthur Ludd. I accept that he had the highest mind you or anyone else ever saw. I just want to say that there are times when I could wish you had never met him.”

He knew that this remark was unworthy of him, that he should no more criticize Nancy’s relationship with Sir Arthur Ludd than he would attack her for being moved by St. George, Sir Isaac Newton or the Charge of the Light Brigade. No fair-minded man could dare say that it was Sir Arthur Ludd’s fault that he had made such an impression upon Nancy all those years ago in blitztime England, where, by crude overstatements of her age and experience, she had promoted herself a tiny uniformed job ministering to the American Forces at Rainbow Corner and other relief points. Nor could you fault Nancy on account of the deep and lasting emotions aroused in her by this dedicated baronet, wounded at Dunkirk, invalided, an occasional lecturer to troops on technical aspects of warfare. It was in this capacity that he had first met Nancy. But he had also been immediately welcomed to the laboratories and back rooms of the Ministries of Aviation and Supply, where the brightest and most profound of Britain’s technicians were winning the war. Knowledgeable people said he was the brightest and most profound of them all. He also knew the work of the Restoration Dramatists by heart, and for relaxation used to translate them into Aristophanic Greek.

Nancy looked at her husband, saying nothing, for fear of disturbing the hush of the cricket field, but telling him with her beautiful eyes that he had said a coarse and hurtful thing. She had never concealed her feelings about Sir Arthur Ludd. Her memories of him during those months in England were not guilty but ennobling. She had made it clear when she married Francis that she intended to bring these memories along, together with a few pieces of fine furniture and glassware from her old family home in Vermont. Far from cluttering their Manhattan apartment, they would all serve to lend it a note of dignity.

And indeed the wraith of Sir Arthur had in one sense behaved itself unobtrusively. He was rarely spoken of. But one was made sharply aware that from time to time Nancy pursued one train of thought or course of action, rather than another, because she felt it to be in line with the ideals of Ludd. And sometimes when she criticized Francis, and later their daughter Francesca, Francis and Francesca instinctively knew that they must have done something or expressed some thought of a definitely un-Ludd nature.

It was unquestionably “Luddism” — as Francis referred to it when vexed — which had made up Nancy’s mind that this year they would go to England for the summer. At seventeen, Francesca did not seem always apt to appreciate the sort of things Sir Arthur Ludd “stood for.”

He stood for the real England. Not, as Nancy emphasized, that he had been narrow-minded. He had stood, as she recalled, for the real France and the real America too. These were all hard to find. You needed rigorous mental and spiritual training to get to them.

A determined trek to the real England would, Nancy said, do Francesca, and indeed all of them, a world of good. It would lift them, she implied, up toward the Ludd standard. It would be a gesture toward the higher values. Because Francis and Francesca had both chanced to be thinking in terms of Maine, the intervention of the unseen hand of Ludd in their holiday plans seemed particularly irksome.

To Jay Porter, who found himself sitting here damply with the three Mannings watching this cricket, the ghostly presence of Sir Arthur Ludd was even more oppressive. This youth Porter, from Indianapolis, being exposed temporarily to an Oxford education, had latched onto the Mannings while they were viewing Oxford at the end of the summer term. He had rejoiced to find himself at a table with fellow Americans in an overcrowded Oxford restaurant. He rejoiced further to note that one of these fellow citizens was a glorious girl gleaming at him only the table’s breadth away. There was conversation. There were introductions. Parents, in such circumstances, must be accepted as a necessary evil. Jay found the Mannings not evil at all. Yet there were times when he felt that the delightful Mrs. Manning was measuring him with her beautiful eyes against some invisible marking, and finding that he did not measure up.

He mentioned his impression to Francesca. “Probably it’s Ludd,” she said. “Maybe he finds you wanting — in nobility of character, high-mindedness, other-worldliness, strength of purpose, modesty, intellectual genius. Some je ne sais quoi that you don’t happen to have.”

“He’s a liar,” said Jay. “Who is he?”

Francesca explained about Sir Arthur Ludd.

“You don’t even know him?”

“Only mother does,” said Francesca. “But on a spiritual plane I’d say I’m well acquainted with him. I’m familiar with all his little ways.”

“And so it comes to pass,” said Jay, fixing her with burning eyes, “that under the dominance of this myth from the past, you trail about this country suffering experiences sometimes bizarre, sometimes merely horrible, and sometimes both at once, like this. Do you suppose, by the way, that this is the real England?”

“Nothing else was,” said Francesca, wriggling agreeably under the slither of the remaining raindrops over her skin. “People kept telling us ‘this isn’t the real England,’ and then we came to this historic township here with its castle famed in legend, and a cricket match going on and all. And if that isn’t the real England we’ll maybe have to throw in our hand.

“So there we all are,” said Jay, “poor hapless puppets in the hands of Ludd, the sadistic scientist from outer space.”

He sighed, continuing to gaze at Francesca. “You’re not keeping your mind on the game,” she said.

“Like a fish,” he said.

“Me? Like a fish?” Her voice rose to a small shriek. “I like that! Honestly — ”

“Like a fish out of water, I meant,” said Jay hurriedly. “Beautiful, gleaming and wriggling and all in the wrong environment and element.” He peered angrily around at the mackintoshed figures distributed sparsely about the benches.

“Well, mother thinks you’re an undesirable element,” said Francesca. “She feels we didn’t come here to pick up people like you that we could meet by the dozen back home.”

Nancy was turning to shush them again when an intense noise zipped across the playing field like a projectile and seemed to explode at the Mannings’ very feet. The players froze, then stared at the benches on the further side of the field. A moment later the noise was repeated. and this time was distinguishable as human speech.

“Nancy!” was the sound it made; and again, “Hi! Nancy!”

Looked at askance by the players, flaunting a raincoat like a cloak draped from the shoulders of a rowdy sports coat, a bulky figure came straight across the field in a swaggering hobble. From a distance of thirty yards the man began to wave enthusiastically and actually to converse, as though he were talking across the width of a drawing room.

“Nancy, my dear!” he shouted. “Ages since I saw you! What on earth have you been doing with yourself? How’ve you been? Awful lot of ’flu about this year, though mind you the reports may be exaggerated. Nothing to be frightened of.”

By this time he was clumsily hurdling the intervening benches. Members of the Manning party saw looming above them a shoe-leathery face, scarred here and there, it seemed, by a slip of the cobbler’s hand; a Roman nose protruding nobly from it; and eyes both roving and intent with a droop of the left eyelid that made you think of a pirate’s patch.

“Arthur!” said Nancy. “It’s just wonderful to see you. Francis, this is Sir Arthur Ludd. Arthur, this is my husband.”

“Splendid! Splendid!” said Sir Arthur. They started to make room for him on their bench, but he had already hobbled round it and seated himself on the bench immediately behind them.

“No use trying to talk now in this utter discomfort,” he said, leaning forward. “What we’ll do is, we’ll watch this thing for a bit and then we’ll all go and I mean to say as it were.”

Peering around for a moment, Jay saw him extend his legs and throw himself into a semisupine attitude, his arms extended in each direction along the back of the bench.

Francis, Francesca and Jay Porter turned their attention to the game in an awed silence. The personal materialization of Sir Arthur Ludd was as disconcerting as would be a sudden wave and cheery greeting from a symbolic statue on some public building. His presence immediately behind made them all feel that it was their duty to watch England’s national game with an increased semblance of interest.

The ecclesiastical quiet, briefly broken by the eruption of Sir Arthur, had again settled over the field, emphasized rather than shattered by the sound which, Jay was happy to remember, was properly known as the “crack of leather on willow.” The fans maintained an almost eerie silence, commenting on the game chiefly by nods, shakes of the head, and an occasional sigh as of scorn or despair.

“Surely,” whispered Jay to Francesca, “there’s a bit in this piece where someone calls out ‘Play up, and play the game!’ Or have I my facts wrong?”

He had not. At that very moment a hoarse voice shattered the moist peace with an abrupt staccato cry.

“Play up, and play the game!” was its utterance. It ceased, cut off as sharply as it had begun.

Electrified by this noise which came from immediately behind them, the Mannings and Jay Porter looked round. Sir Arthur Ludd was still in his partially recumbent position. His chin had fallen forward to rest on his gaudy tie, the snap brim of his hat almost covered his face. Some of the fans had turned round, too, in irritable curiosity, but there was nothing to connect Sir Arthur with that in spiriting exhortation.

Uneasily the spectators in front of him settled down to appreciate whatever was going on on the pitch. They did not settle for long. The shattering voice came again.

“Jolly well bowled, sir!” it suddenly shouted, “Jolly well bowled!”

Since the bowler was not in action at all at the moment, this piercing piece of applause struck spectators and players alike as painfully irrelevant. All gazed in the direction of Sir Arthur, but it was as though he had never moved. A man sitting next to him gave him an exasperated little nudge, and at the same time moved himself an inch or two away from him on the bench in a gesture of disassociation. Sir Arthur snapped up his chin and pushed his hat back on his head and looked about him with a lofty expression. The people who had been eying him censoriously quickly looked away again. He leaned forward and tapped Francis on the shoulder.

“I don’t know how you feel about it, old boy,” he said, “but it seems to me we’ve seen about enough of this. There’s a bar in the pavilion. Why don’t we all go and so to speak — ”

Nancy’s expression, as Sir Arthur led the way toward a chalet-type wooden building at the end of the field, said that this certainly was going to be a privilege.

“Mother looks,” said Francesca, “as though she was hoping for the best from us and expecting the worst.”

Grimly, Francis braced himself for some high-minded conversation. He felt it his duty to his wife to tell Francesca and Jay to brace themselves for the same. Francesca sighed. Jay Porter looked lovingly at her and glared at the swaggering raincoat ahead of them.

“J’ever hear,” Sir Arthur was saying as they filed into the pavilion, “that story I read somewhere about the man that died suddenly while watching a cricket match? Over three inches of rain had fallen for seven runs, and it was supposed the excitement killed him.” He laughed loudly. A party of Anglo-Englishmen at one end of the small bar displayed disgust at the unseemly jest. Two American airmen at the other end sniggered happily. Sir Arthur rounded on them.

“Just because,” he said sternly, “you people prefer playing rounders with a hard ball, there’s no occasion to sneer at our national game.”

“Well, anyway we paid to see it, didn’t we?” said one of the airmen.

“Not at all,” said Sir Arthur. “You paid to see these magnificent grounds and this historic castle, including its horrific dungeons and the boudoir where Henry VIII possibly made his first pass at Anne Boleyn. And then, today being Saturday, you’ve got the splendid display of cricket at its best thrown in. How much more, may I ask, do you expect for a lousy four shillings and sixpence, with just a very few extras here and there?” The airmen looked at him as unfavorable as did the English party at the other end of the bar.

“J’ever notice,” said Sir Arthur to Nancy, “that something about the game of cricket brings out the worst in everyone? Evil, sour expressions are what we see around a cricket ground. Though mind you,” he added loudly, “it may be of course that only sour and evil people ever go to watch such games.”

“But you were watching, Sir Arthur,” said Francesca. “You were shouting and encouraging them.”

“Wasn’t actually watching,” said Sir Arthur; “just sitting meditating, more or less contemplating my navel. But the crowd likes to hear a cry of ‘Well caught’ or something of the kind from time to time, so I give it them every so often.”

“But why do you come at all if that’s how you feel about it?”

“To make money,” said Sir Arthur. “Ever since I opened the castle grounds to the public I spend every Saturday at least padding about, helping to sort of, as it were. By all means buy us another big drink all round, Manning old man. As I say, it encourages the masses to see the owner in the flesh. People natter about the Duke of Bedford and that three-ring circus or whatever it is he runs at his place, but what I say is where else can you put down a mere four and six pence and be sure of seeing a baronet of ancient lineage and a brilliant scientist to boot?”

He slapped his hand on the bar and looked challengingly around at the company.

“So this is your place?” said Nancy. “I do admire your enterprise, but it must be sad having to sort of hire it out this way. I remember how you used to feel about the family traditions.”

“Comes to that,” said Sir Arthur, “the Ludds have always been in the looting line from way back. Looting and low cunning — that’s how we got the castle in the first place, changing sides at the right moment in the Wars of the Roses. I love to hear the jingle of the cash register behind the bar there, and the merry click of the turnstiles. I love money; don’t you, Manning?”

“Great stuff!” said Manning, in a tone hearty but bewildered.

“And of course the money goes to keeping up your laboratory,” said Nancy. “I read in a magazine somewhere that some o f your researches might ultimately save as many lives as penicillin.”

“Oh, I chisel most of the lab money out of the government,” said Sir Arthur. “Easy enough, you know, if you know where to start chiseling. Thank God, a little title and the old-school tie are still sometimes worth a bit more than honest merit. I spend most of what I make out of this castle racket on strictly personal luxuries — wine, really good cigars, you know, that type of thing.”

“And all the time,” breathed Nancy rather anxiously, “you may be on the verge of something that will save all those billions of lives.”

“Can’t say,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s a tossup. I’m the best man in England in my line, but even so it’s just a tossup. And by George! when one looks around at the citizenry one wonders whether there hasn’t been a bit too much life saving in the past. I intend no personal offense,” he added with an unctious smile at one of the Englishmen who seemed to be on the point of angry protest. “Dear Nancy, how happy I am to see you. Should we all take a little stroll round the place? I like to have a quick look round before closing time.”

Beside a path behind the pavilion an irregular semicircle of large stones was visible in the rank grass. A neatly painted notice said: “Possible site of Druid ring and altar. Here young maidens may have been bound shrieking on a midsummer’s night, and at dawn pitilessly sacrificed to the Sun God.”

“They may, at that,” said Sir Arthur.

“Is there historic evidence for it?” asked Jay.

“Naturally not,” said Sir Arthur. “We are dealing here with the prehistoric.”

Where the path adjoined a well-trodden dirt track a signpost announced: “To the camp for nudists.”

“A small idea I picked up from the Duke of Bedford again,” said Sir Arthur. “The papers were full of his plans for inviting one of the nudist societies to camp on his grounds.”

“I don’t know that I specially want to see a lot of nudists,” said Francesca, as they moved in the direction of the sign.

“You aren’t likely to,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s all right for Bedford down there by the muggy Thames, but I can’t see any society of nudists being fools enough to come up to a chilly rainswept place like this. I don’t want any charges of misrepresentation, and this, as the sign indicates to everyone of average intelligence, is simply a camp available to nudists should they wish to take advantage of it. Do any business today, Tom?” he inquired of an elderly man who was folding a small collapsible chair and preparing to leave his position in front of a low fence, enclosing what seemed to be an extensive copse where the undergrowth grew thick beneath the trees. “Tom,” explained Sir Arthur, “has the binocular concession here. Lets them out at a shilling a time for people who want to get a good view of any nudists there may happen to be.”

“Only six bob today, sir,” said the old man. “There ain’t the interest in the naked human form there used to be. I suppose the movies have damped the ardor, as you might say.”

“But if there aren’t any nudists there anyway?” said Jay.

“In my young days,” said the old man sternly, “we’d have paid our bob just on the off chance.” He looked Jay up and down with sad contempt and ambled away, the binoculars which had been in such poor demand bumping against his hip.

As they approached the castle itself, the last of the bedraggled visitors were leaving, complaining loudly among themselves at the extortionate price they had been asked for tea and buns. “Imagine that,” said Sir Arthur. “Complaining about a few bob extra for tea in such sur- roundings. Some of these people have no historic sense.”

“Rugged-looking old place,” commented Francis Manning.

“You bet it’s rugged,” said Sir Arthur. “I had to pay a gang of workmen a packet to knock it about till it got the proper fifteenth-century tone. Actually, most of it was run up less than a hundred years ago by my great-grandfather when he made a bit of money out of a small coal mine he chanced to find. At that, he forgot battlements. Had to put them on myself. In my opinion to invite the public to a castle that has no battlements is equivalent to obtaining money under false pretenses. It’s the same with dungeons.”

By way of a long winding staircase they descended to the dungeons. Here was black gloom, alleviated only by the faint light from slits high in the walls.

“Mind the rack, my poppet!” Sir Arthur cried in agitation as Nancy bumped against a dimly seen contrivance of poles, rollers and pulleys. “It’s good, but it’s flimsy. I knocked it together myself. And now that all those eager students of the medieval way of life have gone, we might have a little light on the scene.” He snapped a switch, flooding the large circular room with electric light. “When I opened for business,” he said, “believe it or not, this place was scarcely furnished. Not a rack, not a thumbscrew, not a garrote in the place. Terrible condition to leave a dungeon in.” While his visitors surveyed a satisfying array of instruments of torture, each with its notice luridly describing its uses, Sir Arthur approached what seemed to be a stone coffin set against one of the walls. Its top was roughly chiseled with some vaguely heraldic device and the notice beside it said: “Tomb of the first Sir Arthur Ludd circa 1300. Please do not touch.” Sir Arthur drew a key from his pocket, inserted it in a lock cunningly concealed in the heraldry, and threw back the lid.

“In addition to thumbscrews and such,” he said, “another thing I personally expect to find in a cellar is booze. Now what will you so to speak — ”

The supposed tomb of the first Sir Arthur was indeed well stocked both as to quantity and variety of liquor. “Porter, my dear boy,” said Sir Arthur to Jay, pouring whisky lavishly and setting the glasses on a table otherwise occupied only by a number of skulls, “just pull up a couple of coffins from the corner over there, will you, and we’ll make ourselves comfortable.”

Having drained his glass and refilled it, Sir Arthur patted Nancy cozily on the thigh and looked her over admiringly. “Lovely,” he said. “All such changes as can be observed are for the better. You don’t mind” — he turned to Francis — “my making passes at your wife? It isn’t as though I saw her every day.”

Francis also drained his glass and re-filled it. “It seems to me,” he said, his voice rising somewhat, “that you’ve been making passes at my wife for the past eighteen years or so. Furthermore, she has reciprocated your — so far as I am concerned — unwelcome advances. You and your high-mindedness! I could sue you for alienation of respect.”

“What the devil d’you mean?” boomed Sir Arthur, his nose deep in his glass. “Are you aspersing this woman? I could sue you for slander. We may be a second-rate power, but we’ve still got our lawyers.”

Nancy rose suddenly and stood over Sir Arthur, her foot tapping dangerously on the stone floor.

“You’re entertaining us very nicely, Arthur,” she said, “but what about your ideals and higher aspirations that you used to tell me about?”

“Yes, indeed,” interrupted Francesca. “Those ideals and standards of yours have been pushing me around for years.”

“And I, let me tell you,” said Jay Porter, also rising and standing over the baronet, “have suffered the indignity of being looked on as an unworthy squire of this beautiful and innocent girl because the Ludd yardstick says so. You’ve deliberately humiliated me.”

“But I mean as it were sort of,” said Sir Arthur, “I’m a perfectly ordinary sort of a chap.”

“That’s not the way we heard it,” said Francis.

“You wormed yourself into our home as a paragon,” said Francesca. “You caused friction and resentment.”

A mournful voice was heard calling from a long way off at the top of the stairs.

“Have you got the key of the blood cupboard there, Sir Arthur? Execution block needs a new coating. Lot of visitors today and you can’t stop some of them fingering the bloodstains.”

Sir Arthur got to his feet. “Excuse me,” he said. “There’s a special bloodstain I make up in the lab. They must put it on in the evening; otherwise it’s still sticky in the morning. Bit too realistic.”

The visitors stared at one another as the noise of his feet stumped away up the stairs.

“And that plausible rogue,” said Francis after a silence, “has been imposing on us all these years.”

“He’s a genuine scientist,” said Nancy.

“I don’t doubt it. The point is that as a high-minded arbiter of ethical and social behavior he has been an impostor all this time. I told you I wished you had never met him.”

“But I’m so glad I’ve met him again,” said Nancy. “Otherwise he’d have gone on and on forever being a cause of friction. As a common human being he’s harmless.”

“As a common human being,” said Francesca, “he’s sort of nice.”

“Maybe,” said Francis, “but as an ideal he was hell.”

“But he won’t be any more,” said Nancy. “As an ideal I’ve dropped him.”

Francis kissed her warmly.

“In that case, may I yet dare to hope?” said Jay Porter. He kissed Francesca lightly on the cheek.

Sir Arthur came stamping down the stairs. “Had to find the key for him,” he said. “People like blood. Have some more whisky. But wait a minute!” He had an air of sudden recollection.

“Weren’t we just having an awful row?”

“It’s over,” said Francis. “You’ve exploded and we like you better that way.” “Your presence in the flesh has brought happiness and harmony to all” said Jay. “Now that you’re a human being,” said Francesca, “I shall call you uncle.mI think I’ll kiss you.”

“Do that,” said Sir Arthur, “and then I’ll kiss your mother.”

“Meanwhile, I’ll have some more whisky,” said Francis.

“It’s good stuff,” said Sir Arthur. “Been maturing for an awful long time. The only genuine antique on the place.”

Featured image: The visitors surveyed the instruments of torture, each with a notice of luridly describing its uses. (Erik Blegvad, SEPS)

Considering History: Operation Paperclip and Nazis in America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

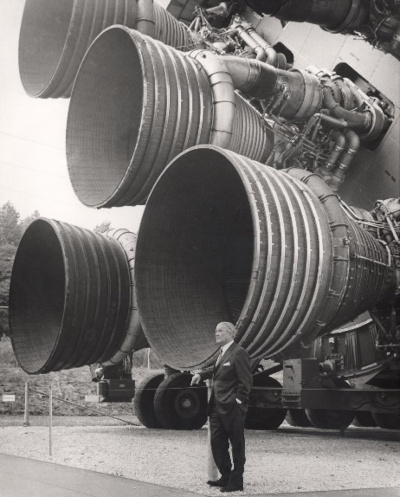

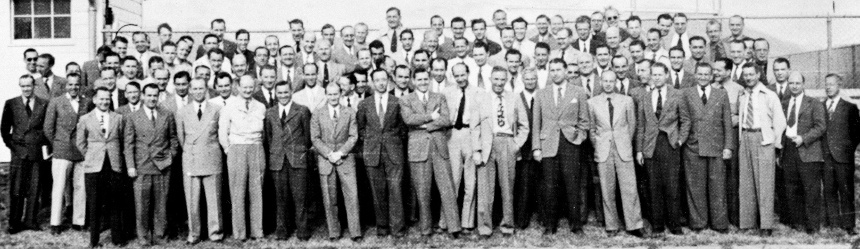

On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

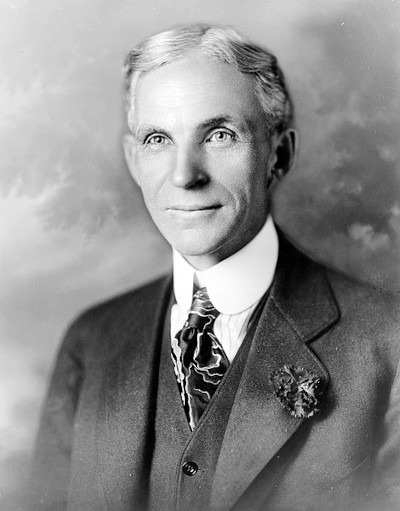

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.

After his 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh was another of the period’s most famous Americans, and in 1938 Lindbergh likewise received a Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, this one from German air chief Hermann Goering himself. Over the next two years, Lindbergh’s public opposition to American conflict with Nazi Germany deepened, and despite subsequent attempts to recuperate that opposition as fear over Soviet Russia’s influence, Lindbergh’s views depended entirely on anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that equaled Ford’s. In a September 1939 nationwide radio address, for example, Lindbergh argued, “We must ask who owns and influences the newspaper, the news picture, and the radio station, … If our people know the truth, our country is not likely to enter the war.” Seen in this light, Lindbergh’s role as spokesman for the era’s America First Committee makes clear that that organization’s non-interventionist philosophies during World War II could not and cannot be separated from the antisemitism and Nazi sympathies of figures like Lindbergh and Ford.

American Nazism was much more than just a perspective held by elite anti-Semites — it was very much a movement. And like so many problematic social movements, it featured a demagogic voice to help spread its alternative realities — in this case, the Catholic priest turned radio host Charles Edward Coughlin. By the time World War II began, Coughlin had been publicly supporting both Nazi Germany and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories for years; his weekly magazine, Social Justice, ran for much of 1938 excerpts from the deeply anti-Semitic Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a text that contributed directly to Hitler’s views and the Holocaust. Both Social Justice and Coughlin’s radio show were hugely popular throughout the 1930s — a separate post office was constructed in his hometown of Royal Oak, Michigan just to process the roughly 80,000 letters he and show received each week—illustrating that American Nazism and anti-Semitism were widespread views in the period.

No moment reflected that American movement better than the February 20, 1939 rally that brought more than 20,000 Nazi supporters to New York’s Madison Square Garden. The rally was put on by the German American Bund, a national organization which consistently sought to wed pro-Nazi Germany sentiments to direct appeals to mythic images of American identity and patriotism. To that end, the rally was held on George Washington’s birthday, and the stage featured a portrait of Washington flanked by both American flags and Nazi flags/swastikas. After the rally opened with a performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Bund secretary James Wheeler-Hill proclaimed in his introductory speech that “If George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler.” And in his closing speech, Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn went further, arguing that “The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of white gentile stock, and an American citizen imbued with patriotic zeal.”

Yet many other Americans expressed their patriotic zeal by opposing this Nazi rally. An estimated 100,000 protesters gathered outside the Garden, dwarfing the 20,000 or so Nazi sympathizers inside. The protesters featured World War I veterans, members of the Socialist Workers Party, and countless other local and national organizations and communities. And inside the rally, one young man took such opposition a step further: Kuhn’s speech was interrupted when Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish-American plumber’s assistant from Brooklyn (and future World War II naval sailor), charged the stage. Greenbaum was attacked by Bund guards, pulled away by police, and charged with disorderly conduct, for which he paid a $25 fine to avoid a 10-day jail sentence. But he was not the least bit apologetic, later stating, “Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing Hitler’s behind while thousands cheered? Well, I did it.”

Greenbaum and his fellow protesters make clear that these pro-Nazi sentiments were in no way unopposed in, nor exemplary of, 1930s America. But neither can those figures mitigate the troubling realities of the rally and its reflection of widespread American support for Hitler and the Nazis, support that included some of the nation’s most famous individuals as well as tens of thousands of other Americans. In a moment when Nazi imagery and sentiments have returned to American social and political debates, we would do well to remember their deep roots in our culture.

Featured image: German American Bund parade in New York City in 1937 (Library of Congress)

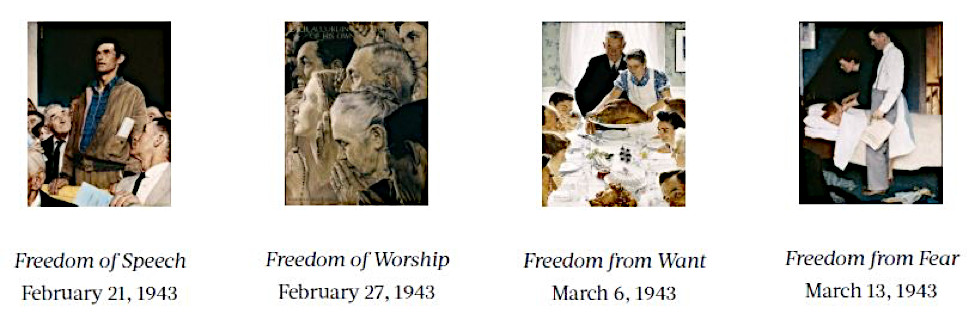

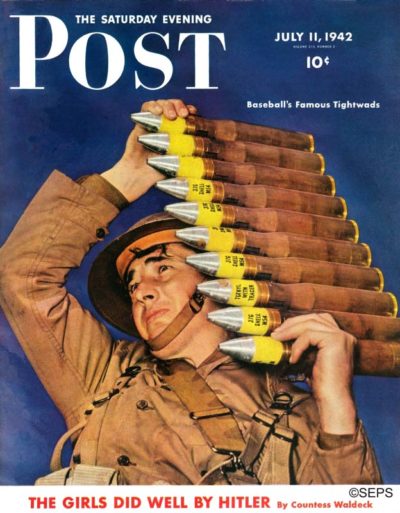

Rockwell Files: Reflections of a Hero

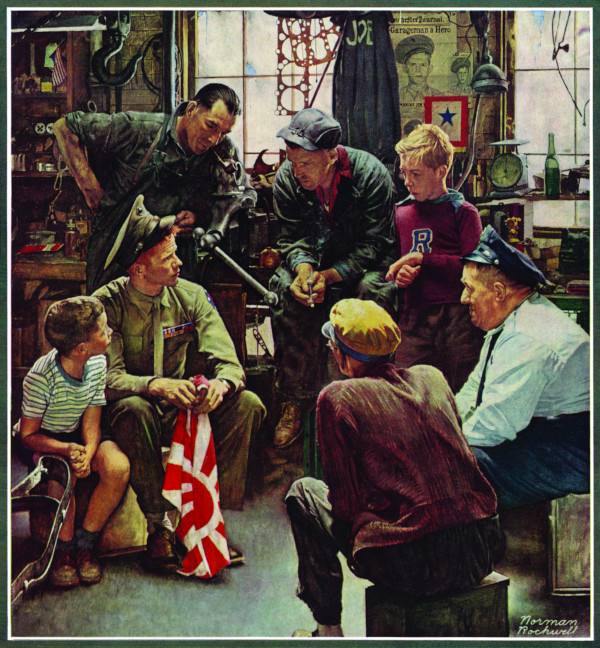

Homecoming soldiers were a popular subject for illustrators in 1945. But for this end-of-war cover, Rockwell took an unusual approach to capturing a veteran’s welcome home.

A traditional cover would have shown a G.I. standing tall and proud among civilian admirers, and Rockwell had produced a cover like that after the last war. It showed a tough, confident doughboy surrounded by adoring younger boys. But at the end of this world war, he gives us a slim, young Marine sitting on a box. As if to emphasize his youth, he is seated beside a little boy who is mimicking his pose.

The newspaper on the wall gives us his back story: The mechanic who’d enlisted for the war has now returned a hero, probably from the Asian theater, judging by the flag he is holding. But, instead of recounting tales of glory, he is looking up with a thoughtful, almost troubled expression at the boy who has just asked him a question.

Rockwell was a master at conveying the subtleties of human expression, and it’s clear his intention wasn’t merely to show a hometown boy back in familiar surroundings, but also to capture the newly returned veteran’s feeling of isolation — knowing he can never adequately convey to the folks at home the things he experienced in the war.

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: (Norman Rockwell / SEPS)

The True Story of Kelly’s Heroes

When Kelly’s Heroes hit theatres 50 years ago this week, it came amid a run of incredible success for its star, Clint Eastwood. While the film was not his biggest that year (that would be Two Mules for Sister Sara), it earned mostly positive reviews, recouped its budget, produced a Top 40 hit with the song “Burning Bridges,” and went on enjoy cult status and a place on many lists of the best war films. Most of the negative reviews focused on the uneasy balance between violence and comedy, but Arthur D. Murphy’s dismissal of the film as “preposterous” in Variety is ironic in hindsight. It certainly might seem that the idea of American soldiers in World War II teaming up with German locals to steal gold behind enemy lines is a flight of fancy; the shocking thing is that part is absolutely true.

The trailer for Kelly’s Heroes. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Kelly’s Heroes drew attention from the outset for the obvious reasons, like its cast. Eastwood’s star had been rising steadily for years, coming off of the Sergio Leone “Man with No Name” trilogy, WWII drama Where Eagles Dare, and other Westerns, while the following year would bring him The Beguiled, Play Misty for Me, and his most famous character in Dirty Harry. Kelly’s Heroes co-stars Telly Savalas and Donald Sutherland had both been standouts in The Dirty Dozen; Sutherland had also made a war picture mark in M*A*S*H earlier in the year. Don Rickles was, well, Don Rickles, and Carroll O’Connor was a tireless and familiar character actor one year out from his iconic turn as Archie Bunker.

The plot of the film follows Private Kelly (Eastwood) who discovers the existence of a cache of German gold after capturing a Wehrmacht intelligence officer. He assembles a misfit crew (including Sutherland’s tank squad), and the group makes a sustained effort to find and capture the gold. After fighting their way through a German tank blockade, the soldiers end up making a deal with the last German tank crew to share the gold. The characters split nearly $900,000 apiece and go their separate ways before they’re caught. And yes, something very similar to that actually happened.

The movies theme, Burning Bridges by The Mike Curb Congregation, went Top 40. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Mike Curb Congregation – Topic / Universal Music Group)

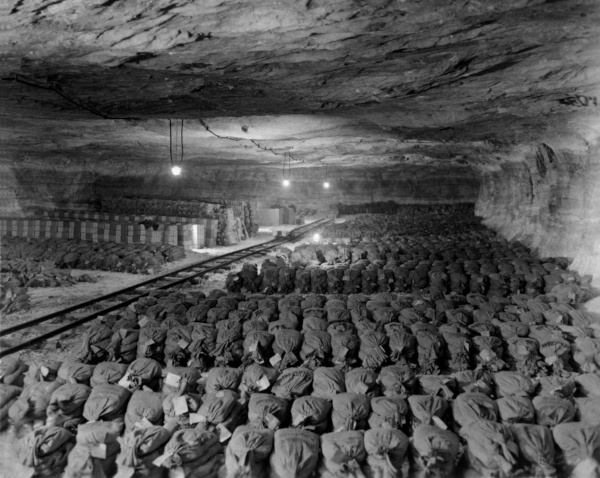

Writer Troy Kennedy Martin based the screenplay on an incident that he learned about from, of all places, The Guinness Book of World Records. “The Greatest Robbery on Record,” first listed in 1956 (and holding the spot until 2000), “was of the German National Gold Reserves in Bavaria by a combination of U.S. military personnel and German civilians in 1945.” MGM was so excited by the prospect that their head of production, Elliot Morgan, wrote Guinness for more information. Guinness’s understanding was that more details than that weren’t really available, possibly due to pieces of the story being classified. Martin used the entry as a starting point and wrote the screenplay.

However, the moviemakers weren’t the only intrigued parties. Ian Sayer is a British journalist, entrepreneur, and historian who has led an extremely colorful life. He founded a delivery service that helped pioneer overnight door-to-door delivery on the European continent. His work debunked fake Hitler diaries. And beginning in 1975, he started work on a book that would uncover the true story behind the gold heist.

Sayer’s book with Douglas Botting, Nazi Gold: The Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And Its Aftermath finally saw publication in 1984 (a second version, Nazi Gold: The Sensational Story of the World’s Greatest Robbery – And the Greatest Criminal Cover-Up, was published in 2012). The books detail that the U.S. Government covered up the theft of millions in Nazi gold from the German National Gold Reserve in Bavaria. The heist was executed by members of the U.S. military cooperating with former German officers, including one-time members of the Wehrmacht and SS. When Sayer sent his information to the U.S. State Department in 1978, it set the wheels turning for an investigation that began in the early 1980s. Eventually, the U.S. recovered two of the gold bars, identified by Nazi-stamped markings, and announced the finding in a press release in 1997. The two bars were valued at over $1 million and eventually found their way to the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold, the body that recovers and redistributes the gold that was seized by the Nazis during the war.

There’s one final twist. In 1984, Sayer spoke to Members of Parliament in an effort to get information about Nazi gold held by the Bank of England. Jeff Rooker, an MP who he had spoken to on the matter, asked Sayer in 1988 to check out an aid fund to ensure that the money was getting to the veterans it was supposed to serve. It turned out that that the citizen who had asked Rooker about the aid fund had been a survivor of the Wormhoudt massacre, when 90 unarmed British troops were killed by the SS in 1940. The officer responsible for the slaughter was SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who had also guarded Hitler’s bunker and disappeared after World War II. Amazingly, Sayer realized that he’d met Mohnke while researching Nazi Gold without realizing the man’s identity; Sayer informed the authorities, leading to investigations into Mohnke from multiple countries. He was never charged due to insufficient evidence, and lived until 2000.

Today, Kelly’s Heroes is regarded as a classic war film, noted for its ensemble, its humor, and its willingness to show the dark moments of war even among a more lighthearted story. But the story of the film rests atop a much more complex true story, elements of which still remain hidden from view. It’s a good reminder that even as much as we think we know about history, there are always some secrets, and maybe some gold, hidden somewhere.

Featured image: Shutterstock

D-Day and General Eisenhower’s Greatest Decision

Generals don’t usually see off the troops. It’s not like Mom and Dad saying goodbye to Johnny at camp or college.

But there Ike was. At the airfield on the eve of D-Day, chatting up some of his soldiers.

He was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe on the eve of the invasion of France to drive Hitler and his German army out of France and the other occupied countries, back to Germany and unconditional surrender. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who dealt daily with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and France’s General Charles de Gaulle, was talking with men of the 101st Airborne Division, some of them with their faces already blackened for the night mission.

The paratroopers were about to board planes that would drop them over occupied France in the dead of night, hours before the D-Day landings on the beaches. And Ike was there to see them off.

Chatting. Asking questions. Seeing if there was anyone there from Kansas, his home state.

Later, as the planes lifted off, his driver saw tears in Ike’s eyes.

I know why.

And why he surprised everyone, including his aides, when he came out of his office as the minutes ticked down to D-Day saying he wanted to go out to the airfield and see the boys off.

He hoped desperately they would come back.

He was gambling they might not.

It was the greatest decision he had to make during the war. Not his decision to go on June 6 — after canceling the planned June 5 landings due to bad weather — but the one I heard him publicly reveal for the first time. It was to a group of 165 high school and college newspaper editors and photographers gathered in the ballroom of the Drake Hotel in Chicago on Saturday morning, January 18, 1947.

He had agreed to meet with the student press club sponsored by the Chicago Daily News, which, as a staff member at the newspaper, I had proposed, organized, and directed when I started writing a column for students in the Greater Chicago area the previous year. After introducing Ike, I took my place at a table at the front of the ballroom, facing the rows of students, as Ike stood at the end of the center aisle, hands clasped behind his back, military style.

He fielded questions on a variety of subjects, including the fact he’d originally planned to go to Annapolis, but then discovered he was over the age limit. He switched to West Point. Questions ranged from other aspects of his personal life and career to world affairs.

As President Harry S. Truman had done the year before, he doubled the allotted time scheduled. But as he closed in on an hour, he said he would take three more questions. The last one:

“General Eisenhower, what was the greatest decision you had to make during the war?”

He turned and started to pace three feet in front of me. A slow, measured step that matched the measured words as he spelled out the situation for the students.

From the earliest stages of planning, it was deemed vital to have a port that would enable the Allies to bring in the massive reinforcements needed, from tanks and trucks to artillery pieces and machine guns, not to mention men. That port would be Cherbourg, which led to selection of the landing points on the coast — five beaches: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword. And then the obvious:

“To ensure the success of the Allied landings in Normandy,” he said, “it was imperative that we prevent the enemy from bringing up reinforcements. All roads and rail lines leading to the areas of fighting on and around the beaches had to be cut or blocked. If reinforcements were allowed to reach the areas of fighting there, in our first, precarious attempts to get a foothold on the continent, the whole operation could be jeopardized. The landings might fail.”

A factor in the planning: the countryside beyond the beaches in some places was not the usual meadows and fields, but bogs — low, swampy areas that the Germans would flood. The few causeways that traversed the area between the beaches and the inland area were the only means of getting from the beaches to the mainland. Or vice versa.

To seize key roads and crossroads, paratroopers would be dropped inland in the early morning hours of D-Day. Enter the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

But just days before, on May 30, a high-ranking, trusted aide came to Ike, asking him to call off the airborne landings. I learned later when I read his book, Crusade in Europe, the aide was British Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory. He had been assigned to the Allied Forces with the title of Allied Expeditionary Air Force Commander in Chief, which made him the air commander of the invasion. He apologized for being so late with his concern. But he’d been going over it, and over it, and he felt the casualties would be too great.

“Casualties to glider troops would be 90 percent before they ever reached the ground. The killed and wounded among the paratroops would be 75 percent.” Or 13,000 of the 18,000 men. Not only unconscionably high, but so high the mission would be doomed.

Ike thanked him for bringing his concern to him, said he would consider it. He had a few days to think about it, but then the time came to decide. And as Ike reached this point in his account of events, his step slowed ever so slightly, as if the weight of the decision settled over him again. As he put it in his book, “It would be difficult to conceive of a more soul-wracking problem.”

He reviewed the planning process for the invasion that had begun months before. The mission had been reviewed countless times as Allied officers and their aides went over every aspect of the massive invasion. Hundreds of planes on airfields ready to take off for their respective missions. More hundreds of troopships, landing craft, tanks, trucks, machine-guns. Some 5,000 ships, the largest armada ever assembled. A military operation with myriad moving parts.

As Ike weighed Leigh-Mallory’s request, he kept coming back to the fact that the mission had been reviewed countless times. And, as he put it, “The success of the landings on the beaches might well turn on the success of the paratroopers behind the lines.”

What Ike also made clear that Saturday morning in Chicago was that he couldn’t let the boys land on the beaches without having done everything he could to keep the Germans from bringing up reinforcements.

Still pacing, almost thinking out loud, he said it: “I couldn’t permit that, either.”

Step slowing to a stop, he turned to face the students. “I let the order stand.”

Silence.

Then, a little less somber: “The airborne boys did their job. And, I am happy to say, the casualties were only 8 percent.”

With that, and an exchange of formalities, he was gone.

It was the following year, the Fall of 1948, that I learned how surprised his aides were when, on the eve of D-Day, as the tension mounted with each sweep of the second hand around the clock, Ike came out of his office and said he wanted to see the boys off.

His driver, a WAC (Women’s Army Corps) Captain in the U.S. Army mentioned this when she met with the student editors. And so Kay Summersby drove Ike out to see them off. “We covered three separate airfields before night fell,” she said. She also said he ordered the unit commanders to order each group to break ranks and forget about military formalities.

By chance some years later, I met a woman who had been a Red Cross worker in England during the war, and was one of those at the airfield passing out coffee and doughnuts to the boys when Ike drove up. She handed him a cup of coffee, then noticed his hand was shaking so badly she was afraid the hot coffee would spill over and burn him. Gently, she eased the cup out of his hand.

Stephen E. Ambrose reported the mingling and chatting with the 101st Airborne paratroopers — Ike at one point asking if anyone was from Kansas — in his book D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle Of World War II. He concluded his segment on Ike’s visit with the lift-off:

The planes started their engines. A giant cacophony of sound engulfed the airfield as each C-47 in its turn lurched into line on the taxi strip. At the head of the runway, the pilots locked the brakes and ran up the engines until they screamed. Then, at ten-second intervals, they released the brakes and started down the runway, slowly at first, gathering speed, so overloaded that they barely made it into the sky.

When the last plane roared off, Eisenhower turned to his driver, Kay Summersby. She saw tears in his eyes. He began to walk slowly toward his car. “Well,” he said quietly, “it’s on.”

Five years after Ike stood mere feet from me, answering the student editor’s question, I was watching the noon news on the TV set in my living room. Another Saturday. The Republican National Convention had wrapped the night before with Ike’s speech to the delegates accepting the Republican nomination for President of the United States. To my surprise, the studio announcer broke into the news coverage to report Ike had surprised everyone by leaving his suite at the Blackstone Hotel.

He’d gone down to the street, turned the corner, and started walking up South Michigan Avenue, with an ever growing flotilla of media. He went into the Congress Hotel and headed straight to the ballroom, where there was a luncheon in progress: A reunion of men of the 82nd Airborne Division.

When they saw him, they were on their feet. Cheering. Clapping. Whistling. Smiling as broadly as he was. No longer in military uniform, the soon to be 34th President of the United States, had dropped in on his boys once again.

He moved to the dais and stopped behind the podium, the famed Eisenhower grin as wide as I ever saw it. A TV camera zoomed in until Ike’s face filled the TV screen.

And I saw the tears start down his cheek.

Featured image: Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower addresses paratroopers before they board their planes for Europe on D-Day. (Library of Congress)

Remembering the Fallen of World War II

One of the most searing scenes of the 75th Anniversary of D-Day ceremonies last year was at the Normandy American Cemetery on the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. Beautiful in its way, the grass in the 172.5 acres so green it might be in a Technicolor movie, the chalk white crosses and Stars of David on the graves — more than 9,380 — lined up in a symmetry that is breathtaking.

Beneath each cross and star lies a fallen serviceman, a G.I. we honor — every day, I hope, but especially on Memorial Day, the day set aside each year to remember the fallen. Rightly so, as the inscription on one marker puts it:

Into the great mosaic of victory

This priceless jewel was set.

So, too, the fallen in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery — 50.5 acres in Luxembourg, with 5,076 graves — one of the white crosses there marking the final resting place of General George S. Patton, “Old Blood and Guts.” He led his Third Armored Division 100 miles on icy roads in bitter cold weather in December 1944 to break the German encirclement of Bastogne in The Battle of the Bulge.

The deadliest U.S. battle of World War II, fought when the war in Europe was supposed to be over.

The surprise German attack had just started the day I approached the entrance to the Chicago Daily News Building on December 18, 1944, in hopes of getting a job as a copygirl at the Chicago Daily News. The Allied retreats each day, before the eventual advances, made up the headlines my first weeks there. Newspapers were all around me, editions delivered by copyboys coming up from the press room with the latest edition every couple of hours, distributing them to the various news desks and editors. Big black headlines were followed by stories with the details, notably the siege of Bastogne, which the Germans surrounded early on in the fighting.

Because the German attack pushed a long, deep curve in the Allied lines before the tide turned, it came to be known as The Battle of the Bulge. The daily battles, artillery shellings, and tank attacks left those rows of white markers in the Luxembourg American and Memorial Cemetery.

The war in the Pacific was equally costly.

It came into my life the morning of February 1. When I came to work I was told not to report to my usual post at the city desk but to go to a far corner of the city room, a square of four empty desks. On the cleared top was a stack of copy paper, a pair of scissors, a glue pot, and a streamer of Associated Press (AP) copy.

The streamer was not a story but a list of names of the men the Allies had just rescued from a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines — a military operation so dramatic, daring, and dangerous it came to be known as “The Great Raid.” A raid so dramatic, daring, and dangerous that John Wayne led the rescue mission in the 1945 film Back to Bataan. In a story in the late edition, AP put it this way:

SIXTH RANGER BATTALION CAMP, LUZON — (AP) — There is a long, dusty, twisting land near here which should become a war monument, for today it bridged two worlds. It leads across the plain toward the death camp where 513 prisoners of war were rescued by American Rangers and Filipino guerrillas.

To get the names of the rescued men out to their loved ones as quickly as possible, AP was listing them as they received them, not taking time to put them in alphabetical order. That was what I was to do.

I cut the names of the men apart, long narrow strips, and laid them out on the desk top. When a deadline approached, I reached for the glue pot and made a wide strip down the center of a sheet of copy paper, and stuck the names down. I remember that while they were secure, the glue did not reach the ends … and I can still see those ends curling up.

Copyboys would come for the list for the next edition and regularly bring me a new AP streamer with its list of names.

I finished just after lunch and settled in at my regular post at the city desk, ready to answer calls of “Copy!” and take stories to the copydesk or get clips from the library. And when things grew quiet late in the afternoon, I had time to read the latest edition, just dropped off at a nearby news desk.

Amongst all the happy photos of local families beaming at family pictures of their rescued sons or husbands, boyfriends or brothers, were the first stories about the men and the toll their years in the POW camp had taken.

There were those so weak, emaciated, a Ranger could carry two men on his back. Some limped from beriberi. The legs of some were scored by tropical ulcers and other diseases, and there were those who looked up helplessly from litters.

They talked in low tones of Japanese brutality and the Death March of Bataan, of the final terrifying week of bombing and bombardment that hit Corregidor, of men dying like flies, of disease, of ten hours daily in prison camps, under the hot sun in fields, or waist high in water of rice paddies under hard eyes, of frequent beatings and shootings.

They recalled when 10,000 men at the Cabanatuan prison camp used to spend all day strung out in line for a canteenful of water from one of the camp’s four spigots.

Now, they lined up for a supper of boned chicken, peas, beans, fruit salad, jam and cocoa — a veritable banquet after the starvation fare of the Japanese prison camp.

Invited to ask for more and eat all they want, one of the men said, “Where we come from they put you in the guardhouse if you asked for more.”

It was only with time that I realized each name on those AP streamers — soon a narrow slip of paper on the cleared top of the dark green metal desks — was the name of a man who had not only survived a Japanese POW camp but the Bataan Death March, one of the most horrific episodes of the war. So named because 10,000 of the 76,000 men who had surrendered when Bataan fell to the Japanese died during the five-day, forced march —66 miles in jungle heat to the Japanese prison camps. Some guards took the men’s canteens and emptied them of water so they would have nothing to drink. Others killed, bayoneted, and beat men who tried to get a drink from the gushing artesian wells they passed.

And so, while I don’t remember the names I alphabetized that day, I remember the men whose names were on those narrow slips of paper with the ends curling up — what they endured in their service to their country.

One of the survivors, Glenn Frazier, gave an account of the horrors in the Ken Burns documentary for PBS The War. It appears in the companion book, Frazier saying:

I saw men buried alive. When a guy was bayoneted or shot, lying in the road, and the convoys were coming along, I saw trucks that would just go out of their way to run over the guy in the middle of the road. And likewise the rest of the trucks, and by the time you have fifteen or twenty trucks run over you, you look like a smashed tomato. And I saw people who had their throats cuts because [the Japanese] would take their bayonets and stick them out through the corner of their trucks at night and it would just be high enough to cut their throats. And I saw men beaten with a rifle butt until there just was no more life in them. I saw Filipino women [who tried to bring us food or water] cut. Their stomachs were cut open. Their throats were cut. I saw Filipino and Americans beheaded just with one swipe of a saber.

An officer who’d been keeping track of the cut-off heads he saw as he passed stopped counting at twenty-seven lest he go mad.

Soon the headlines moved on again. This time, to Iwo Jima. The Marines landed there February 19.

The flag raising atop Mount Suribachi as they took control of part of the island would become one of the most famous pictures of World War II, or any war, for that matter. It would win the Pulitzer Prize for AP photographer Joe Rosenthal, go on to become a huge bronze statue — the centerpiece of the United States Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia — and an array of U.S. postage stamps through the years.

Many a headline reported the battle, the progress, the fierce resistance the Marines encountered, before the fighting ended March 26. But it was only when I read the book Flags of Our Fathers by James Bradley, son of one of the flag-raisers, that I fully appreciated what the Marines faced.

“The Marines fought in World War II for forty-three months,” Bradley said. “Yet in one month on Iwo Jima, one third of their total deaths occurred. They left behind the Pacific’s largest cemeteries: nearly 6,800 graves in all, mounds with their crosses and stars.”

Someone chiseled these words outside the cemetery on Iwo Jima:

When you go home

Tell them for us and say

For your tomorrow

We gave our today

Featured image: Marines raising the American flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945 (photo by Joe Rosenthal / public domain)

Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation

The city was thronged. On Thursday, September 3, 1936, tens of thousands of people lined the streets of Des Moines, Iowa, to catch a glimpse of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived by train at the Rock Island station at noon. Troops from the Fourteenth Cavalry stood at attention as uniformed buglers greeted the commander in chief, who emerged from Pioneer, his private carriage, balanced on the arm of his youngest son, John Roosevelt, smiling broadly and waving to a cheering crowd.

Nearly half a century later, at least one admirer could recall the day in great detail. A young sportscaster at Des Moines’s WHO radio station had been visibly thrilled as he hurried to the window of his offices on Walnut Street to take in the motorcade. “Franklin Roosevelt was the first president I ever saw,” Ronald Reagan told a gathering of Roosevelt family and New Dealers at a 1982 centennial celebration of the 32nd president’s birth.

Speaking in the East Room, Reagan, now the 40th president, paid tribute to the Democrat for whom he had voted four times — in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. “Like Franklin Roosevelt, we know that for free men hope will always be a stronger force than fear, that we only fail when we allow ourselves to be boxed in by the limitations and errors of the past.” The president then offered a toast: to “Happy days — now, again, and always.”

The reference was unmistakable, for Franklin Roosevelt and the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” were inseparable in the political imaginations of Americans. The song entered the nation’s political consciousness at the Democratic National Convention at the Chicago Stadium in 1932. Roosevelt, who was seeking the presidential nomination, had planned to have “Anchors Aweigh” as his theme song, reminding delegates and listeners on the radio of his tenure as assistant secretary of the Navy during the Great War. From his command post at the Congress Hotel, Roosevelt adviser Louis Howe listened to his secretary, a fan of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” sing it out for him. Impressed, the wizened political sent word to the hall to change course: “Happy Days Are Here Again” was now the FDR standard.

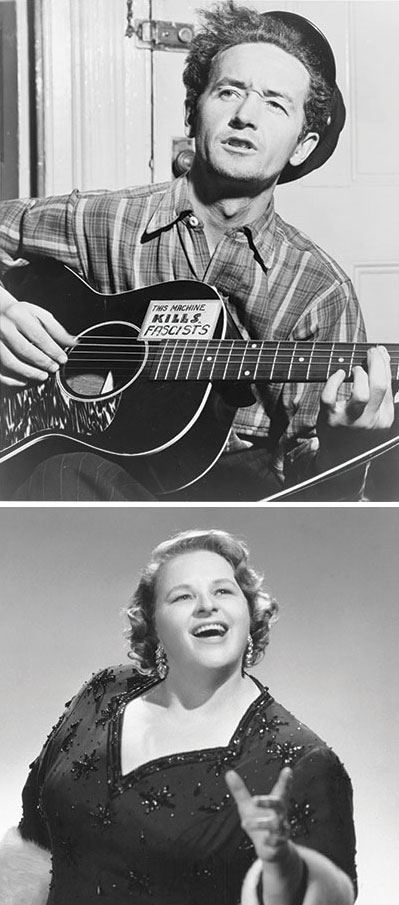

In 1938, the drift toward chaos and bloodshed in Europe prompted the composer Irving Berlin to excavate a song he’d written in 1918, “God Bless America.” He arranged for the singer Kate Smith to perform it on her CBS radio show on Armistice Day 1938, and Smith would record the number in early 1939. In the late 1930s, fearing Hitler, listeners did not have to think hard about what she meant when she spoke of “the storm clouds” gathering “far across the sea” or “the night” that required “a light from above.” Woody Guthrie, though, heard something else in Berlin’s verses: a triumphalism that portrayed America simplistically and sentimentally. And so Guthrie wrote a reply. Initially titled “God Blessed America,” it became “This Land Is Your Land,” a song that grew in popularity during and after World War II. (By 1968, Robert Kennedy was suggesting that “This Land Is Your Land” ought to be the national anthem.)

In wartime, the simpler the song, the more powerful it was, not least because life under fire was so emotionally complicated. The most moving music of the war was the music that moved the troops themselves — songs of longing and loss, of love and hope. There was “We’ll Meet Again,” “You’ll Never Know,” and big band numbers by Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and others. It was the age of such songs as “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” and Miller and the Andrews Sisters each had a hit with “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else but Me).” Miller, whose “Moonlight Serenade” was a signature song, lobbied to join the military once America entered the war. (Born in 1904, he was in his late 30s.) Bing Crosby wrote the government a letter of recommendation, saying that Miller was “a very high type young man, full of resourcefulness, adequately intelligent, and a suitable type to command men or assist in organization.” Commissioned in the Army Air Force, Miller set out, he said, to “put a little more spring into the feet of our marching men and a little more joy into their hearts.” Regular military bands resisted Miller’s attempts to bring the music forward from the Great War to the 1940s. “Look, Captain Miller,” one is said to have complained, “we played those Sousa marches straight in the last war and we did all right, didn’t we?”

“You certainly did, Major,” Miller replied, according to the story. “But tell me one thing: Are you still flying the same planes you flew in the last war, too?”

On a broadcast on Saturday, June 10, 1944, a few days after D-Day, he announced, “It’s been a big week for our side. Over on the beaches of Normandy our boys have fired the opening guns of the long-awaited drive to liberate the world.” The band’s opener that day was “Flying Home,” a jazz number by Lionel Hampton (Ella Fitzgerald would later sing a powerful version) that, for African-American GIs, signified a journey toward the kind of freedom at home they’d been fighting for abroad.

Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the afternoon of Thursday, April 12, 1945, in his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia. As the president’s body was being moved to the train for the trip to Washington, a naval chief petty officer, Graham Jackson, tears streaming down his face, played “Going Home” on his accordion.

Woody Guthrie may have offered the most timeless memorial to the fallen Roosevelt. In a song addressed to Eleanor, Guthrie remembered FDR as a providential figure:

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt, don’t hang your head and cry;

His mortal clay is laid away, but his good work fills the sky;

This world was lucky to see him born.

There is, really, nothing more to say on the matter. The world was lucky to see him born.

Jon Meacham is a Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer and author of The Soul of America (2018). Tim McGraw is a Grammy Award-winning country music artist.

From Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation by Jon Meacham & Tim McGraw, published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Merewether LLC and Tim McGraw.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.

How the Allies Tried to Exorcise Nazism

Germany’s army may have surrendered on May 8, 1945, but Nazism never admitted defeat.

Though their nation was in ruins, millions of Germans still believed in Nazism. Nazi officials, however, found it expedient to profess their ignorance, resistance, and innocence of their government’s war crimes. Others denied their affiliation with the Nazis while remaining quietly committed to the policies of the now-dead Hitler.

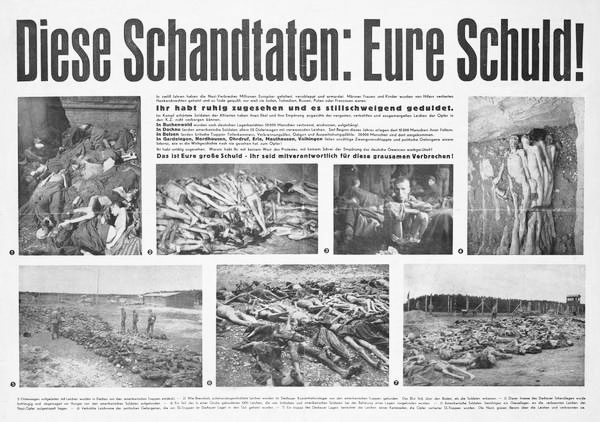

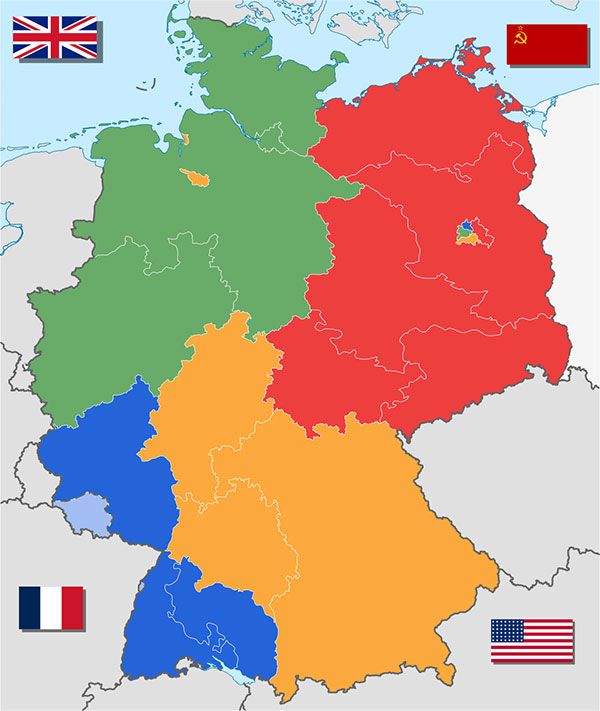

The Allies recognized the appeal of Nazism to a defeated people. The movement had sprung from Germany’s humiliating defeat 27 years earlier. To eradicate the idea, all four major powers — America, Russia, Britain, and France — agreed to a plan of denazification. They would hold the supporters of the Nazi government accountable for their crimes, eradicate Nazi regalia, and present the country with the scope of Nazi crime.

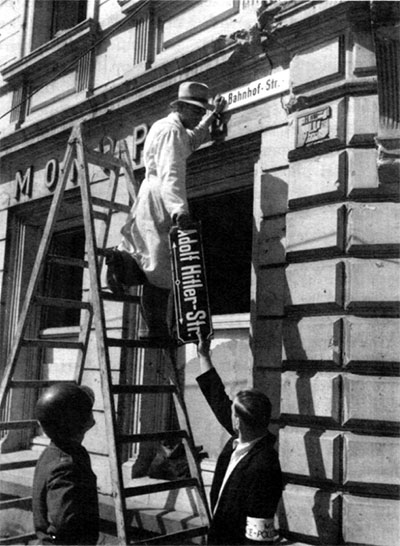

Under this plan, Germans who held government offices under the Nazis lost their jobs. The Nazi party was banned, and advocating its ideas was punishable by death. The swastika and other party symbols were removed from public view.

All Germans had to fill out a questionnaire about their involvement in Nazism.

Ex-Nazis and local residents were forced to walk through concentration camps, or made to watch movies of the abuse of Jewish prisoners.

The German people were also told they bore responsibility. They were given booklets with photographs of concentration camp victims, bearing the words “You are guilty of this!”

The Allies each occupied a sector of the country and divided the task of investigating the 45 million Germans who worked for the Nazis. They included not just members of the army and secret police but also industrialists, arms dealers, and business owners who’d employed Nazi slave labor.

The original idea was to hold all Nazis accountable, but this proved impractical. There were simply too many to investigate. And the U.S. military was bringing 785 top Nazi scientists and engineers to America without any inquiry into their politics.

In the American sector of Germany, over 170,000 Germans could be held until their case could be heard by a tribunal of American officials. Following their hearing, they were assigned to one of four groups.

- Group I: Major offenders, who were subject to arrest, trial, and a possible sentence of death or long imprisonment. Their public trials, like those held in Nuremburg, were meant to discredit them, publicize their atrocities, and justify Allied justice to the German people.

- Group II: Offenders — activists, militants, and profiteers. They would be sentenced to imprisonment.

- Group III: Lesser Offenders who weren’t imprisoned but placed on probation, with restricted rights, for up to three years.

- Group IV: Followers, who were prohibited from holding public office, fined, and limited to performing manual labor. Young adults in this category were barred from university admission.

The remainder were classified as “Exonerated.”

The process was laborious and time consuming, and the American soldiers who worked on the tribunals wanted to go home. The Americans gradually handed the job over to the Germans.

Meanwhile, in the French sector, the screening for Nazis became more lax, and the British were soon loosening their standards for prosecution as well. Many war criminals in the American sector fled to the British zone and escaped punishment.

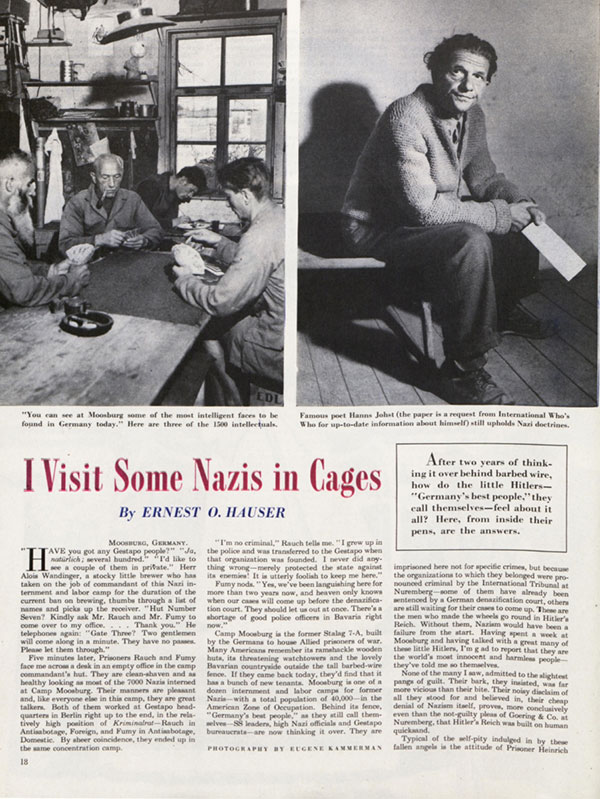

Thousands, though, were still held by U.S. authorities at the Moosburg Prison, formerly Stalag VI-A, Germany’s largest POW camp. Here army officers and high-ranking civilians awaited their hearings.

When Post journalist Ernest O. Hauser visited Moosburg in 1947, [“I Visit Some Nazis in Cages,” Oct. 11, 1947] his first request was to interview captured Gestapo officers. The two he met assured him they’d done nothing wrong. They’d been police men who were ordered into the Gestapo. Since then, they had “merely protected the state against her enemies.”

Hauser also interviewed Heinrich Hoffer, Hitler’s photographer and the man who introduced him to Eva Braun. Hoffer’s defense was he’d only joined the Nazi party because an American editor had offered him a thousand dollars to photograph Hitler, and he had to be a party member to get close to the Fuhrer.

After several more interviews with suspected Nazis, Hauser wrote, “I’m glad to report that they are the world’s most innocent and harmless people — they told me so themselves.”

Inmates who hoped to be classified as a Category III or IV had to provide evidence they were one of the “good” Nazis. The best approach, Hauser wrote, was to claim they had secretly helped Jews. “In hearing the prisoners talk about the kindly interest they always took in their Jewish compatriots,” he wrote, “one might easily think that the Nazi Party was a society for the care and protection of Judaism.”

Hauser noted the thousands of “intellectuals” in the camp — highly intelligent, well educated professionals who considered themselves, as did other Germans, as the best people in Germany. These academics and professionals were responsible for the highly efficient Nazi government. Now they demanded release, claiming to be the only hope against communism. “The Bolsheviks are coming!” they cried, according to Hauser “Let us out! We are the saviors of Europe.”

In truth, their expertise was sorely missed in a country where inexperienced civilians were trying to revive the country. Immediately after the fighting had stopped, the allies had dismissed nearly half of all Germany’s public officials.

American officers admitted to Hauser that war criminals were slipping through their hands. The guards were underpaid German civilians who, for as little as three packs of cigarettes, would look the other way as a prisoner slipped out.

When Germans took over the tribunals, they began speeding up the hearings. They released the younger detainees by declaring anyone born after 1919 (i.e., those who’d been adolescents when Hitler came to power) had been “brainwashed.” In later decisions, the German panels determined 90 percent of detainees didn’t require a trial. Even so, by 1947, over 90,000 Germans still remained in detention.

The results of denazification were not encouraging to American authorities. Much of the German population remained in sympathy with Hitler and his party, even after the public trials and the publicizing of the Holocaust. In 1946, 37 percent of Germans said the Holocaust was necessary for the security of Germans. In 1952, one fourth of Germans still had a good opinion of Hitler. General Eisenhower believed it would take 50 years for the spirit of Nazism to die.

At least 200,000 Germans participated in Nazi crimes. In a CNN article, German history professor Mary Fulbrook says that the tribunals heard 140,000 cases between 1945 and 2005, but just over 6,650 were convicted.

Eventually, 270 Nazis in were tried in court and found guilty. Death sentences were handed down for 190 (though 28 were commuted to lengthy prison terms). Few of the industrialists accused of profiting from slave labor faced severe punishment.

Of all the top Nazis, seven were sentenced to particularly long sentences in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. The last convicted Nazi was Rudolf Hess, who had been imprisoned since flying to England on a one-man peace mission in 1941. After 46 years in prison, he committed suicide in 1987, at the age of 93.

What of the rest? Those who couldn’t successfully lie about their Nazi past fled the country. In 2012, a British paper studied immigration papers from Brazil and Chile and concluded that 9,000 Nazis from Germany and neighboring countries had fled to South America after the war. Most resettled in Argentina.

The spirit of Nazism never fully died, as can be seen at protest rallies around the world today. But it lost much of its appeal when Germans saw a democratic government, supported by western allies, successfully oppose Russian aggression, and standing firm in West Berlin. They could see two futures, one of abundance with the West or austerity with the East, separated by only a wall. And a younger generation were better informed than they were in the Nazi era. According to one teacher in that 1945 Post article, German youth needed a better spirit of enlightenment and tolerance. As he told Hauser, “Democracy is not just majority rule — it is respect for the minority.

Featured image: Germans removing a street sign named after Adolf Hitler (Wikimedia Commons)

Guide to the Archive: An Intrepid Journalist Covers World War II for the Post

Journalist Richard Tregaskis had been covering World War II since its earliest days. He witnessed the Battle of Midway and he was with the Marines during the first months of fighting on Guadalcanal Island. He also wrote dispatches for The Saturday Evening Post, writing about the dangers that G.I.s faced in Europe and the Pacific Theater.

Saturday Evening Post members can enjoy reading Tregaskis’s articles in our digital archive, along with stories by other greats such as Ray Bradbury, Dorothy Parker, and Jack London.

Articles by Richard Tregaskis

All articles can be found in our digital archives.

“House to House and Room to Room,” February 24, 1945, page 18

“Road to Tokyo—We of the B-29’s Say Good-By,” August 18, 1945, page 17

“Road to Tokyo—‘I Don’t Intend to Ditch’,” August 25, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Disillusionment in Hawaii,” September 1, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—‘Guam—This is It!’,” September 8, 1945, page 22

“Road to Tokyo—‘Fighters Right Close . . . at 7 o’Clock’,” September 15, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Pay-Off Over Japan,” September 22, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—Peace Caught Us Napping,” September 29, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—We Soften the Peace,” October 6, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—The Infantry Never Had it So Tough,” October 13, 1945, page 20

“Road to Tokyo—The Fine Hand of Mr. Suzuki,” October 20, 1945, page 18

“Road to Tokyo—Have We Given Japan Back to the Japs?” October 27, 1945, page 20

“Pappy Hain Comes Home,” January 19, 1946, page 20

“Jim Davis Comes Home,” February 9, 1946, page 17

“Commando Kelly, Businessman,” March 2, 1946, page 22

“A Hot Pilot Cools Off,” March 23, 1946, page 17

“Brash Young Man,” April 13, 1946, page 18

“The Bombardier Who Would Build Cities,” May 4, 1946, page 21

“The Marine Corps Fights for Its Life,” February 5, 1949, page 20

“The Cities of America: Norfolk,” July 9, 1949, page 42

“Gabreski, Avenger of the Skies,” December 13, 1952, page 17

“The Cops’ Favorite Make-Believe Cop,” September 26, 1953, page 24

Featured image: The 160th Infantry on the beach at Guadalcanal (Department of the Army)

Memories of a Women’s College in 1942

Today, it’s a time capsule. A Sinatra record playing on my portable record player as I studied for an exam in U.S. History, the little known “Night We Called It A Day.” Still a favorite. There was a moon out in space/But a cloud drifted over its face/You kissed me and went on your way/The night we called it a day.

The place was my dorm room at Stephens Junior College for Women in Columbia, Missouri, in 1942.

It was a time when men weren’t allowed on dorm floors above the entry lobby except the day of arrival or departure, for hellos and goodbyes and moving trunks. That included fathers. Brothers. Fiancés. It mattered not. And it was standing policy that if you were caught (even seen) in a car with a member of the opposite sex without written proof from home that he was your brother or fiancé, you were subject to immediate and automatic expulsion.