Considering History: Voter Suppression and Racial Terrorism, the Twin Pillars of White Supremacy

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

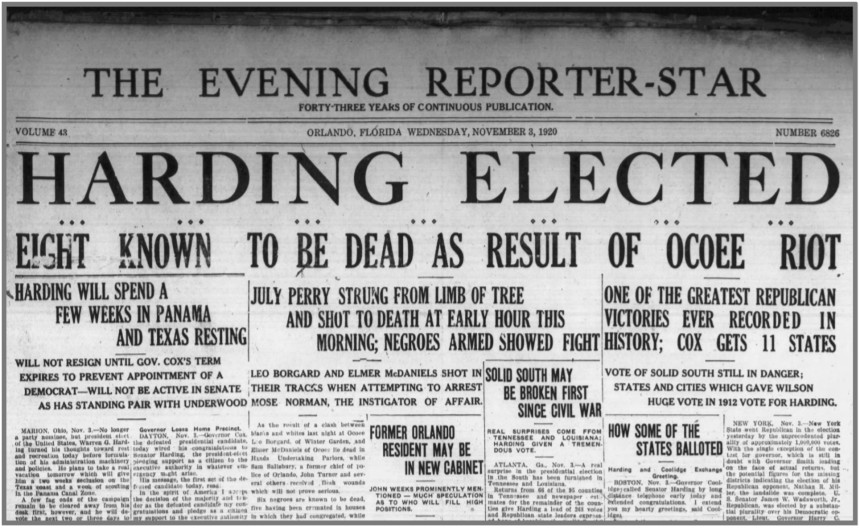

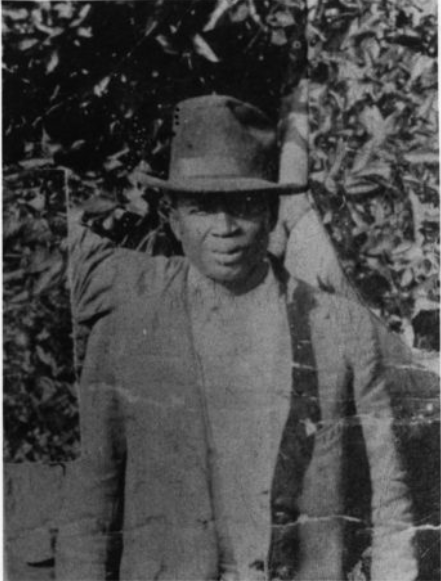

On November 2, 1920, as voters across the country went to the polls to decide a presidential election between two Ohio politicians, Republican Senator Warren G. Harding and Democratic Governor James M. Cox, violence erupted in the Florida town of Ocoee. Local African-American farmer Mose Norman tried to exercise his Constitutional right to vote, and was turned away twice under the pretense of the state’s Jim Crow efforts to disenfranchise black voters. An angry white mob then pursued Norman, laying siege to the home of another man, Julius “July” Perry. Perry fired on the attackers in self-defense, and the mob seized upon that action to terrorize the town’s Black community, eventually killing Perry and more than fifty other African-American residents, burning down homes and businesses, and forcing much of the rest of the community to flee the town.

The Ocoee massacre, known as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” had its roots in multiple historical trends. Like states throughout the Jim Crow South, Florida had developed in the 50 years since the 15th Amendment’s ratification numerous legal measures and social practices intended to make it impossible for African Americans to vote. But those longstanding voter suppression measures were complemented by a much more immediate, violent threat of force: the day before the election, members of the newly resurgent, 2nd Ku Klux Klan had marched through Ocoee, proclaiming through megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And no 1920 act of racial terrorism can be separated from the prior year’s epidemic of such violence, the year-long series of lynchings and massacres that came to be called the “Red Summer of 1919.”

Those factors help us understand the divisions and discriminations at the heart of American culture in 1920. But on the 100th anniversary of the Ocoee massacre, and as we approach another election day, that specific historical event can also help us to better recognize an overarching, profoundly relevant American trend: the way in which voter suppression has consistently gone hand in hand with racial terrorism to prop up white supremacy.

In recent years, we’ve started to do a better job of remembering the history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America through such vehicles as public memorials and pop culture texts, including horrific individual events such as the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the century-long lynching epidemic. But too often the stunning brutality and destruction of those acts of violence can make them seem like impromptu explosions, perhaps reflecting consistent undercurrents of racism but not the result of purposeful, extensive, organized political planning.

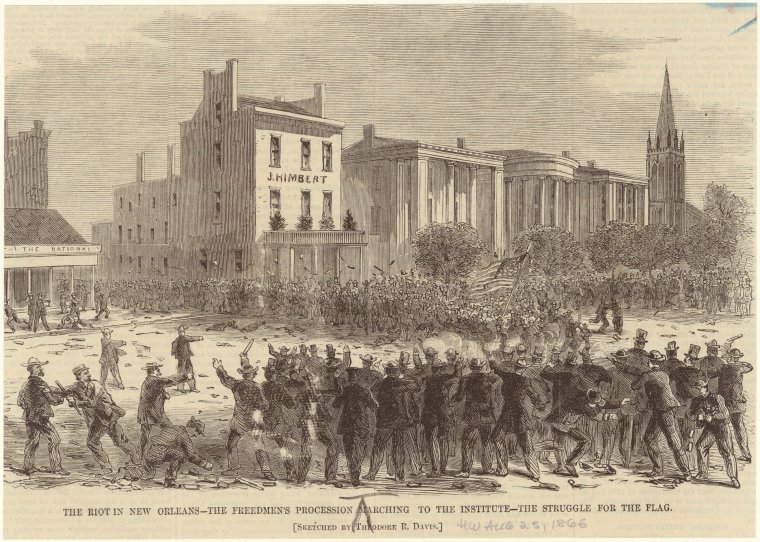

Yet the truth is that these acts of racial terrorism have consistently been tied to planned, organized, systematic plans for voter suppression and related political agendas, as illustrated by not just Ocoee in 1920, but also three prominent 19th century massacres and one from the Civil Rights era. The July 30, 1866 New Orleans massacre began when white supremacists attacked 130 African-American residents marching toward the Louisiana Constitutional Convention at Mechanics’ Institute; the state legislature had passed a series of Black Codes barring Black men from voting (among many other discriminatory effects), and the marchers were hoping to join the Convention to advocate for their rights. New Orleans’ newly re-elected Confederate mayor, John T. Monroe, led a group of ex-Confederates, police officers, and other white supremacists to attack the marchers, starting a massacre that would end with more than 200 African-American Union Army veterans and another 200+ Black civilians killed.

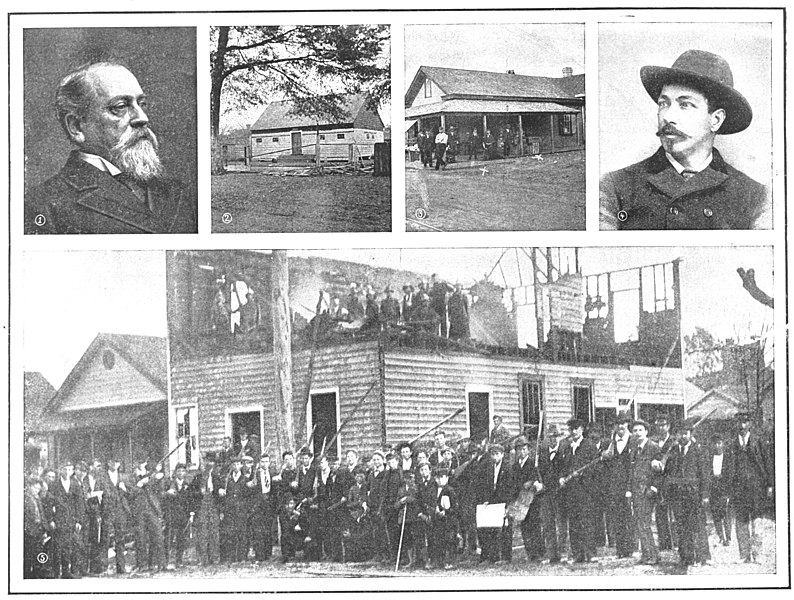

Despite such racial terrorism, African Americans continued to exercise their Constitutional right and active patriotic goal of voting, and were consistently met with extensive suppression and violence. On November 3, 1874, African-American voters at the polls in Eufaula and Spring Hill, towns in Alabama’s Barbour County, were attacked by members of the widespread white supremacist organization The White League; seven African Americans were killed and another 70 wounded. The Barbour County massacre was one of many such events throughout the South on that 1874 election day, a planned campaign of voter suppression and violence after which League-affiliated officials also threw out legitimate votes for Republican candidates and helped install sympathetic Democratic officials in their place (a shift often defined as the beginning of the end of Federal Reconstruction).

The November 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) coup and massacre originated from even more overtly organized voter suppression goals. By late 1898 Wilmington was one of the last communities in North Carolina (and the entire Jim Crow South) not governed by white supremacists — the so-called “Fusion” Party, featuring African-American political figures and their Republican and Populist white allies, had in the 1896 election held on to many of the city’s positions. White supremacists targeted the next election day, November 8, 1898, as an occasion to reverse that trend by force and violence: planning for months an extensive program of both voter suppression and systemic violence, alongside an accompanying propaganda campaign in the media, that resulted in both a coup d’etat and a massacre that devastated the city’s African-American community.

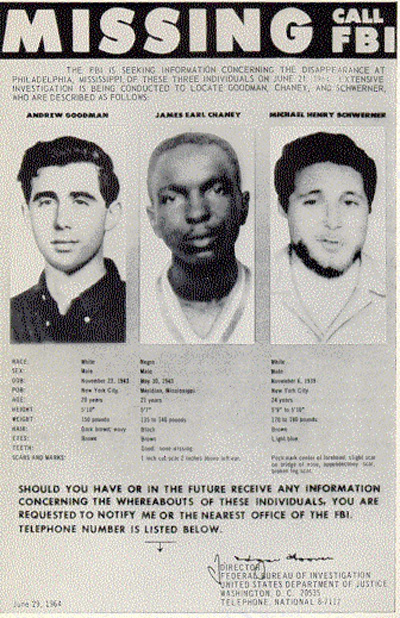

One of the latest documented lynchings, the infamous June 1964 murder of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner near Philadelphia, Mississippi, was similarly interconnected with voter suppression. The three men were working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as part of its Freedom Summer campaign to register African-American voters in Mississippi and throughout the South, and were on their way to a registration event at a local church when they were pulled over by local law enforcement. An extensive FBI investigation determined that members of the Philadelphia Police Department, the Neshoba county sheriff’s office, and the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan subsequently abducted and killed the men. The collaboration between those official and domestic terrorist organizations doesn’t simply reflect their overlapping membership; it also illustrates that the murder of these voting rights activists was part of a political campaign to suppress African-American votes and keep these white supremacist forces in power.

Throughout American history, those who have fought for the right to vote have had to do so in direct opposition to some of the nation’s most powerful forces, including white supremacist suppression and violence. Those battles continue into the 21st century, and as we continue to fight for and to exercise the right to vote, it’s vital that we remember the foundational and consistent ties between voter suppression and white supremacist racial terrorism.

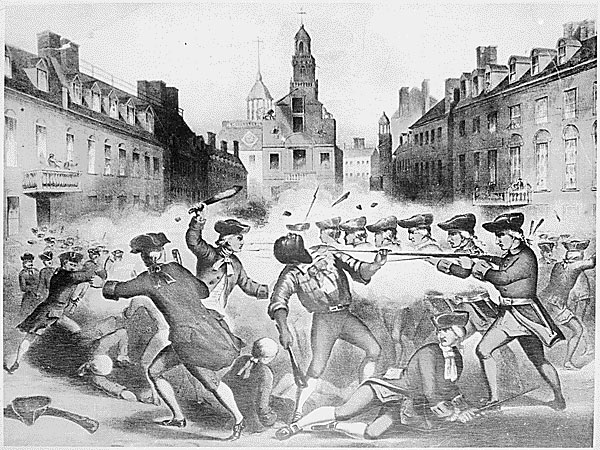

Featured image: The New Orleans Massacre (Artwork by Theodore R. Davis for Harpers Weekly / Wikimedia Commons)

In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When you see the word bulldozer, you might conjure an image of a large yellow machine with caterpillar treads flattening everything before it with its steel-toothed blade. Or maybe your mind goes back to a smaller Tonka version of this mechanical behemoth that you played with as a child. Taken on its own, with no context, bulldozer might even call to mind some serene bovine scene, perhaps Ferdinand the Bull dozing among the daisies.

How jarring, then, to discover bulldozer’s horrible, violent beginnings.

Bulldozer (originally spelled bulldoser) first appeared in the run-up to the election of 1876. That was the final year of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term in office, and he had unexpectedly declined to run for a third term. In his place, the Republican party put its support behind Ohio Governor and former U.S. Representative Rutherford B. Hayes, while the Democratic candidate was New York Governor Samuel Tilden.

This was an important election. All the former Confederate states had returned to the Union, post-Civil War Reconstruction was ongoing, and this was the first presidential election in which African-American men could vote for someone who wasn’t Ulysses S. Grant. The outcome of the election of 1876 would shape the future of the South for years to come.

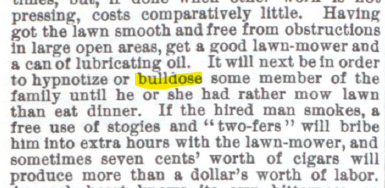

The former slave owners and secessionists in the South knew it, and they weren’t about to sit back and let the North and their former slaves usurp their power and privilege. Despite three new federal laws in 1870 and ’71 designed to protect Black Americans from violence and coercion at the polls, many were bulldosed into silence. Bulldose was a slang term derived from either “a dose fit for a bull” or “a dose of the bull” — the second being a reference to the bullwhip. Bulldosers used physical violence against Black voters either to keep them from the polls or to intimidate them into voting Democratic.

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

The machine we think of as a bulldozer was invented in the early 1920s, and by the initial months of the Great Depression, we start to find the term bulldozer in writing, with that Z further obscuring the word’s origins. The violent, racist origin of bulldozer is one reason many people now use the term earth mover to describe these massive machines.

If you’d like to learn more about the election of 1876 — including commentary from the Post while the election results were in flux — read “The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History.”

Featured image: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

Considering History: Kamala Harris’s Heritage and the Legacies of Slavery and Sexual Violence

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s selection of Senator Kamala Harris to be his vice presidential running mate, a controversial Newsweek article raised questions of whether Harris, the daughter of two immigrants, would be eligible to serve in that role if elected. The article, authored by a right-wing law professor who had previously run against Harris for the position of California’s Attorney General, doesn’t hold legal water; Harris was born in Oakland and so was, from birth, a United States citizen, as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But the article has reignited debates over that Constitutional concept of birthright citizenship, one that President Trump has at various times expressed a desire to do away with.

While Harris’s own citizenship status under that existing law is clear and indisputable (as Newsweek has subsequently admitted), there is another, more genuinely complex part of her heritage and family that has also received renewed attention since the VP announcement. In 2018, Harris’s father Donald, a Jamaican-American immigrant and retired Stanford University economics professor, wrote an article about his Jamaican ancestors in which he argued that he is descended on his father’s side from the infamous 19th century white slave owner Hamilton Brown, who ran one of the island’s largest plantations and was responsible for the importation and enslavement of hundreds of Africans.

Donald Harris’s claims about his relationship to Hamilton Brown have been used by conservative pundits like Dinesh D’Souza and others as a “gotcha” moment, as the basis for arguments that neither Harris nor her supporters can discuss the legacies of slavery and racism since she herself is descended from a white slave owner. But in truth that heritage, which is shared by a significant number of Americans of African descent, reflects one of the most essential and too-often forgotten histories of slavery and the sexual violence that accompanied it. And if we set aside political and partisan concerns, Harris’s story can help us understand those vital histories of slavery, sexual violence, race, and heritage, the legacies of which are certainly still with us in 21st century America.

One of the most consistent and central elements of chattel slavery, as it was practiced throughout the Americas, was the rape of enslaved women by male slave owners. It is difficult if not impossible to ascertain the percentage of enslaved women who were so violated (and thus of enslaved children who were the product of such acts), both because the practice was so ubiquitous and because it was for centuries under-narrated in histories of slavery. The latter trend has been challenged in recent years, as illustrated by historian Rachel Feinstein’s When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery (2019) among other works.

Another recent trend that has made it more possible to grapple with these histories is the rise of ancestry studies and the corresponding use of DNA analysis to trace heritages. For example, the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., a pioneer in the use of such data to analyze individual, familial, and collective ancestries, estimates that “a whopping 35 percent of all African-American men descend from a white male ancestor who fathered a mulatto child sometime in the slavery era, most probably from rape or coerced sexuality.” And since that number reflects 21st century identities and all the other factors that have contributed to them, it likely only scratches the surface of how widespread these practices and their effects were in the era of slavery.

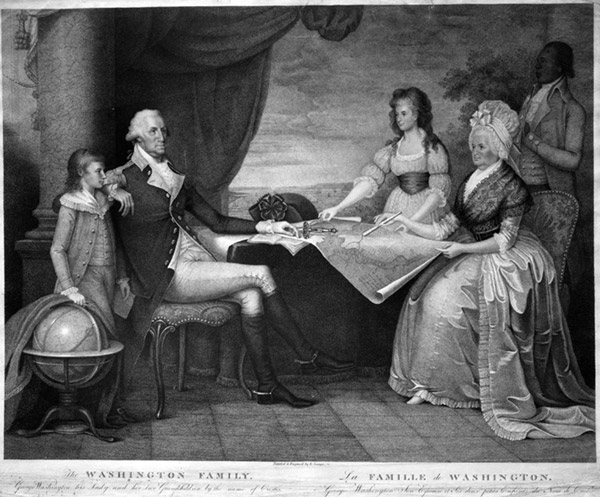

While many of those experiences are unfortunately lost to history, individual case studies can help us engage with the aftermath of sexual violence under slavery. As I highlighted in this July 4th column, the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings offers one particularly prominent such case study. After nearly two centuries of rumors and debate, both DNA analysis and the pioneering work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed have confirmed that Jefferson did rape and father at least one child (and almost certainly six or more children) with Hemings, one of the enslaved women on his Monticello plantation. Historians have only begun to uncover the complex stories of the descendants of those sexual assaults, enslaved young men and women who, despite their famous father and the promise of freedom that came with that status, still experienced some of the worst of antebellum American slavery and racism.

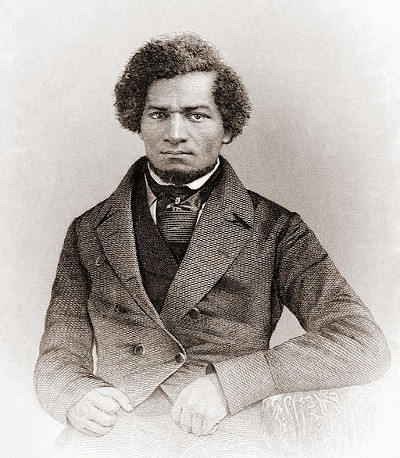

Another of the 19th century’s most famous Americans, Frederick Douglass, experienced life as the child of sexual assault under slavery. In the opening chapter of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass notes his belief that his father, whom he never knew, was the white slave owner of the Maryland plantation onto which he was born. As usual with his autoethnographic works, Douglass uses this personal detail to illuminate social and historical meanings, noting for example that the law making the children of enslaved women themselves slaves “is done too obviously to administer to [slaveowners’] own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.” But Douglass also empathetically notes the potentially painful effects for all involved, from masters having to sell their own children to “one white son” having to “ply the gory lash to his [brother’s] naked back.”

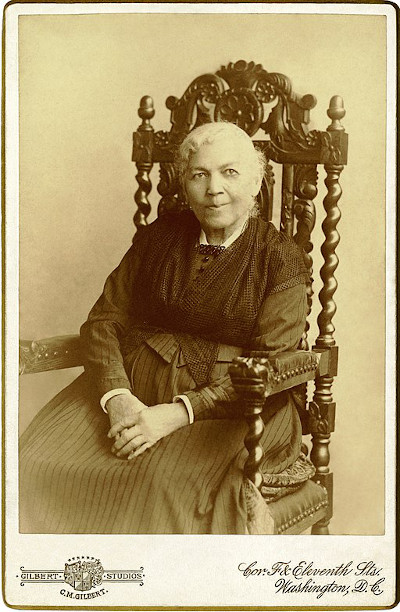

Douglass did not have the chance to know his mother well before her tragic death, so he was unable to write about her perspective. But another prominent personal narrative of slavery, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), captures the experience of enslaved women under the constant threat of sexual violence. As Jacobs puts it in her chapter “The Trials of Girlhood,” “there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men…She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child.” And through her own constant battles with her despicable master Dr. Flint, Jacobs traces how “the influences of slavery had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.”

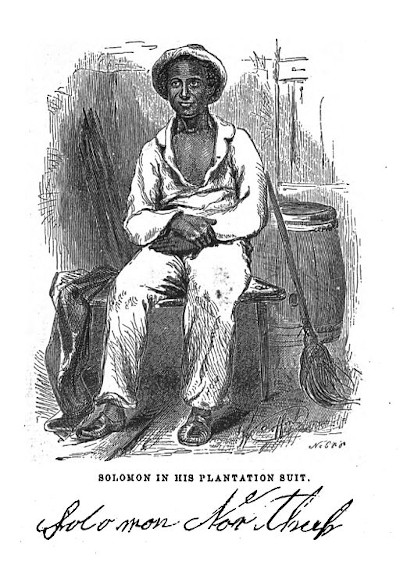

Individuals like Douglass and Jacobs managed to escape the horrors of slavery and publish their stories. But of course the vast majority of both enslaved women raped by their owners and the children of those rapes remained enslaved throughout their lives. We get a glimpse of such experiences in another personal narrative, Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853). At the final plantation to which Northrup is taken, he meets Patsey, an enslaved young woman whose beauty and strong will make her a singular focus of her owner Edwin Epps. If not enslaved, Northrup writes, Patsey “would have been chief among ten thousand of her people”; but on the Epps plantation, this impressive young woman becomes instead “the enslaved victim of lust and hate,” with “no comfort in her life.” Although the illegally kidnapped Northup is eventually rescued from the Epps plantation, he can do nothing for Patsey; a tragic reality captured in a culminating scene from the 2012 film adaptation of 12 Years, as Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) watches Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) recede as he rides away from the plantation.

No one can blame Northup in this moment, as there is nothing he can do for Patsey. But for far too long, both our laws and our collective memories likewise abandoned enslaved women like Patsey and their children to sexual violence and its effects. We cannot change the past, but—with heritages like Kamala Harris’s to help guide us—we can remember those histories and consider all that they mean for all Americans.

Featured image: Kim Wilson / Shutterstock

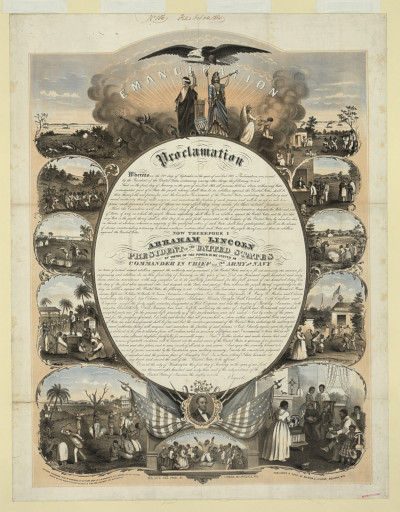

The Voting Rights Act: Passed, but Present

The Department of Justice called it “the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.” It’s played a role in 22 Supreme Court cases. It’s been subject to five major amendments since it originally passed. And yet, there are still those that would try to undermine it. It is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and it has proven absolutely essential to the advancement of the country.

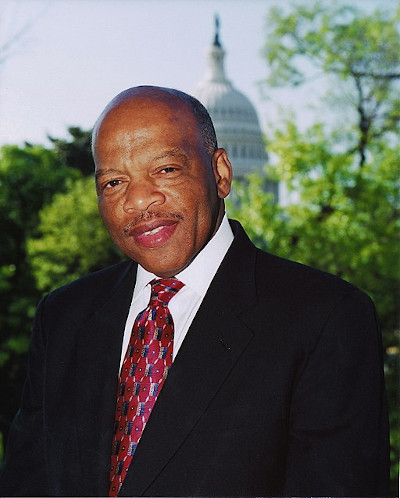

Writ large, the Voting Rights Act is there to prevent racial discrimination against voters. It was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson 55 years ago this week after a particularly contentious and violent few months in America. March of 1965 saw the marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, three events that The Saturday Evening Post covered at the time. The recently deceased Congressman John Lewis led the first march, an occasion that would be become known as “Bloody Sunday,” after many marchers were attacked by police. President Johnson had called for voting rights action in February, but the focus that the marches put on the issue enabled Johnson to push for such legislation during a televised address to Congress on March 15.

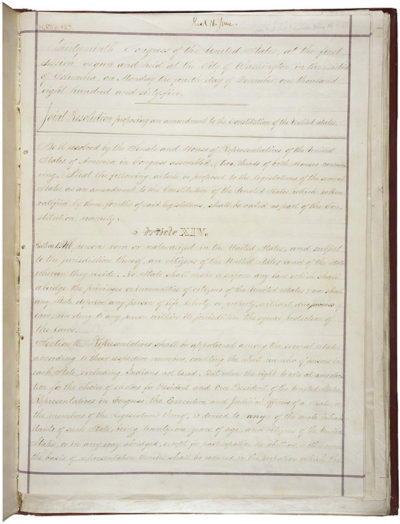

Voting rights had been enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and solidified for all citizens by the so-called Reconstruction Amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th). These three amendments also carry language that allows Congress to pass further legislation in the future, should the need arise to provide additional enforcement. The appropriately named Enforcement Acts followed in 1870, making it a criminal offense to interfere with voting rights while also establishing federal oversight for voter registration and elections. However, two Supreme Court decisions in 1875 defanged the Enforcement Acts, meaning that while these new rules were on the books, they were not uniformly interpreted or enforced throughout the country.

After the advent of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s, Congress would pass three sets of legislation aimed at leveling the playing field in America. Civil rights acts passed in 1957, 1960, and 1964. The broad aim of the 1964 Act was to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places . However, there weren’t enough specifics on voting protections. After the election of 1964, Johnson directed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to write a functionally bulletproof act on voting rights; Katzenbach would get input from both Senator Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader. Mansfield and Dirksen jointly sponsored the Act, and introduced it on March 17, 1965. For his part, Dirksen had been moved to co-sponsor the bill after seeing the violence unfold on Bloody Sunday.

When the bill was formally introduced, a total of 64 more Senators joined as co-sponsors. The House and Senate voted on the Act on August 3 and 4, respectively. It passed the House 328-74, and did the same in the Senate 79-18. Two days later, Johnson signed it into law.

The Act covers two sets of provisions; one set is general, which covers the entire country, and the others are “special,” designated for particular states and local government structures. The Act specifically prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or the spoken language of the voter. Literacy tests, once used in many states to disqualify voters, were banned under Section 2. Section 5 targeted areas that were notorious for a history of illegally disenfranchising voters by specifically noting that they couldn’t make changes to law that countermanded any part of the Act without federal consent.

Of course, very few laws or acts are perfect on the first go-round, so amendments have been applied in subsequent acts. The 1970 and 1975 Acts bolstered discrimination protections for voters with language issues. The biggest 1982 change made it easier to determine if discrimination had happened not just in person, but by the wording used in state laws. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act of 1992 extended protections that were to expire and expanded support for bilingual voters, including Native Americans. The 2006 Act, properly called the Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, extended the special provisions for another 25 years.

If there’s a battleground for the Act in the future, it’s likely on the field of gerrymandering; in fact, the Act has already figured into Supreme Court decisions on the topic. Sections 2 and 5 forbid the creation of voting districts that are made in such a way as to intentionally split up the votes of minorities protected by the Act. However, the Supreme Court has held that you also can’t draw districts to favor particular racial composition. It’s a balancing act that will likely result in more challenges going forward.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented an important step in the United States. Whether or not it was perfect is beside the point. It was attempt to, for lack of a better phrase, get it right. The great contradiction of America is that it rose under the specter of slavery and has to contend with a Constitution that once called Black people 3/5 of a person. The Act itself represented a long overdue shift, a change that attempted to acknowledge and redress systemic problems in the country. While it’s certain that we have many miles to go, the Act remains a crucial lever in the machine of positive change.

Featured image: President Johnson gave Martin Luther King, Jr. one of the pens used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Photo by Yoichi Okamoto; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum. Image Serial Number: A1030-17a. Public Domain.)

Considering History: The Washington Redskins, Oklahoma Territory, and the Myth of the “Vanishing Indian”

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

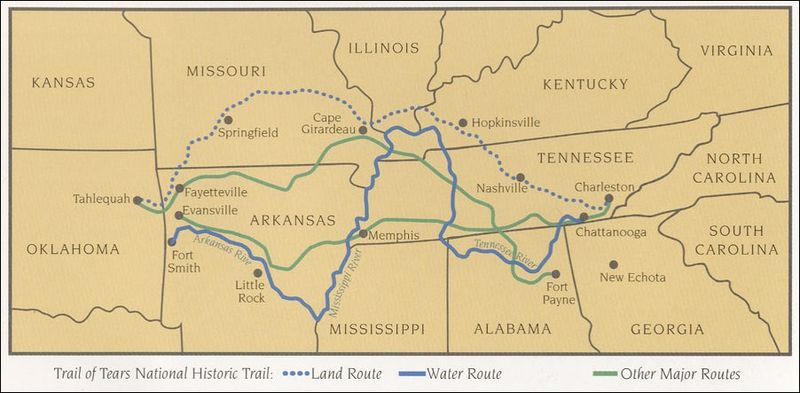

Recently, we have seen two striking decisions on longstanding issues connected to Native American communities. On July 9, in one of its last announced decisions of this session, the Supreme Court ruled that the eastern half of the state of Oklahoma remains “Indian territory” under 19th century treaties that guaranteed the land for tribes forced west on the Trail of Tears, treaties that have never been amended by Congress and so (the Court ruled) continue to hold today. And on July 13, the NFL franchise the Washington Redskins formally announced that the team will be changing its nearly century-old racist name and logo.

The details of these two decisions are quite specific to their respective arenas, and reflect evolving conversations in each case. But taken together, they exemplify two longstanding and contrasting national narratives: those which depict Native Americans through reductive, stereotypical images in order to justify attempts to expel and destroy native communities; and those which recognize instead Native Americans’ foundational and continued presence within America.

In order to justify his proposed, genocidal Indian Removal policy which produced the Trail of Tears, President Andrew Jackson depicted Native Americans through such stereotypical and racist imagery, defining them as savages unable to coexist with European-American communities or indeed exist at all within the expanding Early Republic United States. In his December 1829 first President’s Annual Message to Congress, Jackson argued that “this fate [disappearance] surely awaits them if they remain within the limits of the States.” And in his December 1833 fifth annual message, Jackson went much further, claiming, “That those tribes cannot exist surrounded by our settlements and in continual contact with our citizens is certain…Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

Jackson’s more aggressively racist depictions of Native Americans were complemented by a gentler and more insidious exclusionary perspective that came to be known as the “Vanishing Indian” narrative. Often advanced by figures and communities sympathetic to native rights, this narrative relied on images like the admirable but doomed “Noble Savage” to depict Native Americans as tragically but inevitably disappearing from the continent. James Fenimore Cooper’s bestselling historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826) illustrates this trope, arguing from its title on that its heroic Native-American characters are the “last” of a tribe that in fact still existed in Cooper’s era (and still does in our own). Poet Lydia Huntley Sigourney’s “Indian Names” (1834) is even more striking, as Sigourney uses the persistence of Native-American names on the American landscape to angrily (and inaccurately) lament the destruction of native communities: “Ye say they all have passed away,/That noble race and brave/… But their name is on your waters,/Ye may not wash it out.”

The “Vanishing Indian” narrative became a dominant trope across the 19th century and into the 20th, and in subtle but significant ways informed numerous prominent cultural works, as illustrated by Wellesley Professor Katharine Lee Bates’s 1893 poem “America” that became the lyrics for the song “America the Beautiful” (1910). That trope is most apparent in Bates’s second verse, where she describes America’s origin point: “O beautiful for pilgrim feet/Whose stern, impassioned stress/A thoroughfare for freedom beat/Across the wilderness!” But Bates likewise disappears Native Americans from the idealized images of the national landscape with which her poem opens, and which were inspired by a cross-country train trip from her Massachusetts home to a summer teaching job in Colorado. Bates originally named her poem “Pike’s Peak,” as she wrote it after a day trip ascending the mountain — but, like that name itself, her poem leaves no place for the Ute and Arapaho tribes who had been part of that landscape long before explorer Zebulon Pike arrived.

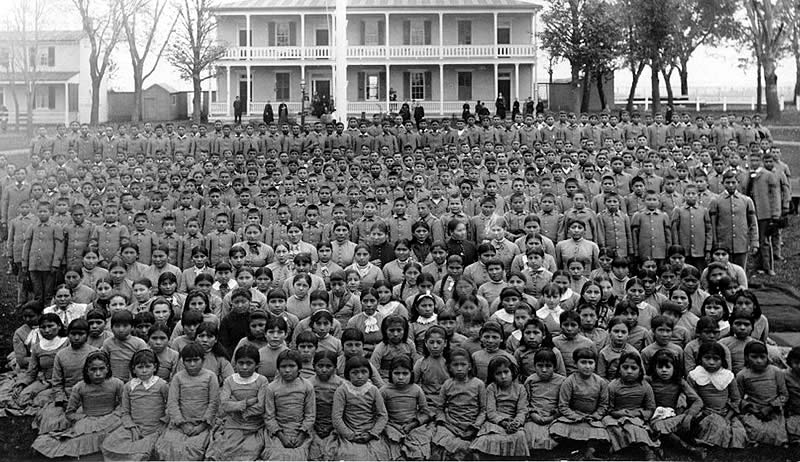

Bates’s 1893 trip took place just two-and-a-half years after the December 1890 Wounded Knee massacre in South Dakota, an exemplification of the far more violent exclusionary attacks upon Native-American communities that continued throughout the 19th century. The late 19th and early 20th century also featured another, even more insidious form of cultural genocide designed to facilitate the disappearance of Native-American cultures: the boarding school movement, which (as Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder and former “Indian Wars” Captain Richard Pratt put it) was intended to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Both these military and educational efforts illustrate that the “Vanishing Indian” was not just a cultural image, but also and most importantly an ongoing white supremacist goal.

As I wrote in this October 2018 Considering History column, Native-American activists and communities have consistently used legal and political means to challenge such attacks and advocate for their survival and their rights. In response to Jackson’s Indian Removal policy the Cherokee nation did so forcefully, with the tribe’s leaders drafting a series of “Cherokee Memorials” to the U.S. Congress that were published in the tribe’s newspaper The Cherokee Phoenix and submitted to Congress to request their assistance. The Cherokee also took their claims to the court system, and the Supreme Court sided with their rights to their land in the Worcester v. Georgia (1832) decision. Jackson famously ignored the Court and proceeded with removal.

Native-American legal and political efforts continued for the next century-and-a-half, including the two prominent moments I highlighted in my earlier column: Ponca Chief Standing Bear’s legal challenge which resulted in the groundbreaking 1879 decision that “an Indian is a person” for purposes of the law (and otherwise); and the numerous activists, including Zitkala-Ša and Nipo Strongheart, whose advocacy led to the watershed 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

The 1960s and 1970s American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis in 1968, continued to utilize the political and legal system to advocate for native lives and rights, while fostering the Red Power and Native-American Renaissance cultural movements of late 20th century America.

These destructive myths and their effects have endured, as illustrated by the horrifically high numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths on Native-American reservations — one more way (among too many, including the kidnappings and murders of native women and the destruction of native lands for pipeline construction) in which native communities continue to face the threat of disappearance. But the Supreme Court decision embodies a perspective in which Native-American rights and presence are seen and supported, and where native communities are defined as foundational and integral parts of America’s history, identity, and future.

Featured image: The delegation of Sioux chiefs to ratify the sale of lands in South Dakota to the U.S. government, December1889 / photo by C.M. Bell, Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

A Black Champion’s Biggest Fight

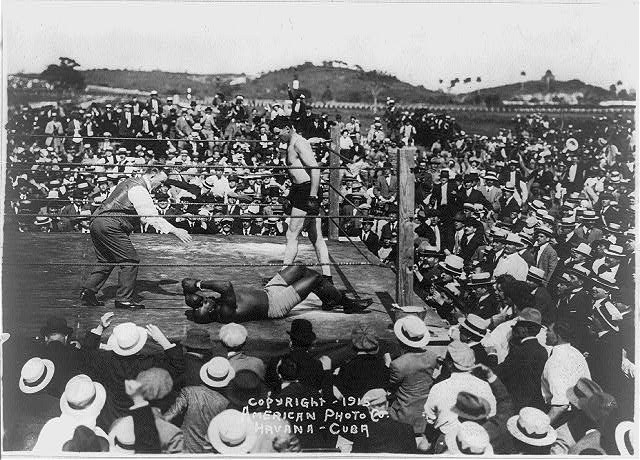

The prize fight held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada was hailed “the Fight of the Century.”

In fact, it was just part of a fight that has been as long as our country’s history.

On that date, African-American champion Jack Johnson was defending his title against Jim Jeffries, as well as defending his race against a racist opponent. His victory detonated America’s first national race riot.

Seven years earlier, Johnson had won the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World.” He then achieved what no black athlete had done before: secured a chance to take a championship title from a white athlete. He boxed and defeated Canadian Tommy Burns for the world heavyweight title.

Johnson’s win challenged the racial superiority assumed by many white Americans. Sports writers and white fans called out for a “great white hope,” a heavyweight boxer who would re-assert white supremacy in the ring. When former champion Jim Jeffries agreed to fight Johnson, he publicly said his intention was “to win the title back for the white race.” And “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro.”

The need to beat Johnson was made even more urgent because of his personality. He was flamboyant, proud, lived lavishly, drove recklessly, and had affairs with white women. So when he climbed into the ring in Reno, Johnson could sense waves of resentment rising from the crowd of 22,000 spectators. Jeffries even refused to shake his hand before the match.

Jack Johnson vs James J. Jeffries (uploaded to YouTube by Classic Boxing Matches)

Twenty-five years later, in an article from the August 3, 1935, issue of the Post, Jeffries said he trained intensively for a year-and-a-half before the match. He got back into shape and dropped his weight from 285 to 220. But just days before the match, he caught a severe case of dysentery that kept him from putting up his best fight. But there was no talk of illness in the days following the match. Then, Jeffries said, “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

White boxing fans who had made the match a contest of the black and white races felt humiliated and angry. They took the fight from the ring into the streets of American cities.

It was not a good year for race relations in America. At least 67 black Americans were lynched in 1910. The Keokuk, Iowa, newspaper that carried the news of Johnson’s victory also featured a front-page story about the black population of Charleston, MO, fleeing the city after two black men were lynched in the street by a gang of white men.

That same paper reported race riots broke out in 50 American cities following the news of Jeffries’ defeat. In New York, according to the Daily Gate City, 11 different racial brawls were reported on the night of the Fourth. Crowds, the paper reported, tried to burn tenements in black neighborhoods. African Americans were dragged from trolley cars in several locations by white rioters and beaten.

In Columbus, Ohio, white spectators repeatedly set upon 400 black men and women who were marching in a parade celebrating Johnson’s win.

A black man buying a newspaper was accosted by a mob, who demanded he tell them what he thought of the fight. “I am neutral,” the man replied. “Let’s kill the [racial epithet],” someone said and the gang approached him. He pulled a knife and held them off until the police arrived.

One reason for the attacks was the fear that African Americans would abandon the deference they were expected to show for the racial majority. A New York Times editorial written two months before the fight stated, “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.”

For some white fans, this championship bout ruined the sport. Eight years later, a humorous note in the October 6, 1923, Post observed, “The papers have been full of the news of prize fights. There must be some mistake about it. As nearly everybody knows, the boxing game in this country died when Jack Johnson whipped Jim Jeffries. It was repeatedly and authoritatively stated there never would be another prize fight.”

Five years later, Johnson was defeated by Jess Willard, a white boxer. Many white boxing fans were exultant. The book Jess Willard: Heavyweight Champion of the World described the aftermath: A sports writer for the St. Louis Times reported, “thousands and thousands of fight fans as well as thousands and thousands of ordinary citizens flooded the downtown streets waiting for the decision.” When they heard Willard had won, “they acted like crazy people.” According to the New York Tribune, the news prompted “respectable business men [to pound] their unknown neighbors on the back and [caper] about like children.”

In a May 8, 1915 editorial, the Post observed, “Critics seem quite unanimously of opinion that this event… is a thing of high importance to the white race. They seem, also, quite unanimously of opinion that Mr. Johnson would have beaten his white antagonist handily if he had not for some years followed an injudicious and deleterious mode of living. We are puzzled to discover a cause for racial pride in the circumstance that a white man was able to whip a black man only after the latter had impaired his constitution by dissipation.”

Three years before the match with Willard, while he was still champion, Johnson had been arrested and charged with violating the Mann Act for driving his white girlfriend “across state lines for immoral purposes.” Johnson fled the country to escape prosecution, which was why his fight was Willard was held in Havana, Cuba.

For years, the rumor persisted that Johnson threw the match, agreeing to take a fall in return for having the charges dropped. Johnson himself contributed to the stories, insisting that he had pretended to be knocked out as part of a deal with the government to drop its charges against him.

But writing for the Post in the April 4, 1925, issue, former heavyweight champion James J. Corbett said of the Johnson-Willard fight, “I was quite near the ringside and watched Johnson closely, and I am morally certain he would never have gone through twenty-six long rounds had the result been prearranged; he would have chosen an earlier round to flop in.” Agreeing with Corbett, Willard said, “If he was going to throw the fight, I wish he’d done it sooner. It was hotter than hell out there.”

But the rumor never stopped hounding Johnson. In the 1940s, having spent a year in jail for the Mann Act violation, he was reduced to boxing in private events. He then got the idea for another way to raise cash, and went to the editor of the boxing magazine Ring, Nat Fleischer.

Fleischer knew Johnson. He had been at ringside when Johnson fell. According to a March 16, 1946 Post interview with Fleischer, “Johnson went down under big Jess Willard’s blows in the twenty-sixth round, rolled over on his back and raised an arm to shield his eyes from the tropical sun as he was counted out.” The arm-raising incident was cited as proof that Johnson had gone into the tank for Willard. Fleischer, convinced that the bout was fought on its merits, always argued that even a semiconscious man would instinctively try to shield his eyes from the blinding rays of the sun.

Despite Fleischer’s certainty of Johnson’s integrity, the Post reported that, “Johnson came to Fleischer with a signed confession stating that he had ‘gone into the water’ for Willard. Nat paid him $250 for it, after the ex-champion had signed an agreement giving him the exclusive rights to publish the story. Fleischer put the document in his safe, where it has since gathered mildew. Fleischer says Johnson has since tried to buy back the ‘confession,’ because he can get a better price for it elsewhere.”

Nat refused to sell. He didn’t believe a word of it, and chose not to publish the confession to protect a boxer, and a sport, that he revered.

In 2018, 72 years after his death, Johnson finally received a presidential pardon for his violation of the Mann Act.

Featured image: Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in 1910 (Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress)

How the Lost Cause Myth Led to Confederate “Monument Fever”

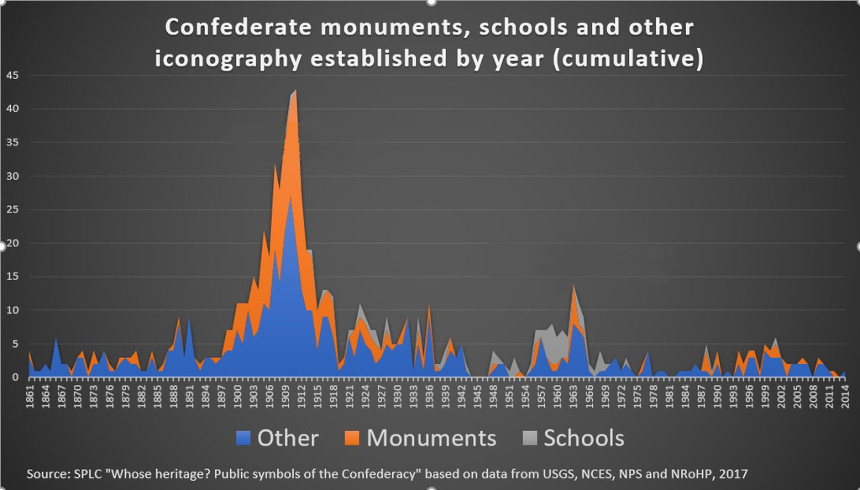

Most Confederate monuments in the U.S. were not erected by the Civil War generation to honor their dead. Instead, they were built almost two generations later. What was the cause of this “Monument Fever” that bloomed in the early 1900s, long after the end of the war?

Few Confederate monuments appeared in the South in the years following the war because of the poverty that the war had brought and the reluctance of southerners to put up statues honoring Confederate heroes while federal troops were still stationed in their states.

Southerners of the late 1860s were more concerned with their personal losses, tending the graves of loved ones and struggling to put their own lives back together. In time, though, the economy revived and more southerners could afford monuments that recalled the Confederate dead and their cause.

In 1894, Caroline Meriwether Goodlett and Anna Davenport Raines founded what would become the United Daughters of the Confederacy. They wanted a group that would tell of the Confederacy’s “glorious fight” and keep the memory of its soldiers alive. The UDC denied that it promoted white supremacy, but it strongly supported the memory of the original Ku Klux Klan and actively supported its revival. As late as 2018, the Daughters’ website declared “slaves for the most part, were faithful and devoted. Most slaves were usually ready and willing to serve their masters.”

Eighteen-ninety-four was a year where the reassuring past seemed to be fading away. The country was in a deep recession. Organized labor was staging strikes in major industries. Disruptive technology, in the form of the telephone, was heralding unexpected change. The Civil War was falling out of living memory; many of its famous veterans had already died. Older southerners were concerned the next generation would only know of the war what they learned from the unsympathetic accounts in northern schoolbooks.

The United Daughters wanted to preserve a history that centered on “The Lost Cause”: an interpretation of the war that gave a nobility to the Confederacy’s cause and its defeat.

The Cause involved far more than defending the property rights of slave holders. The South, it asserted, was defending its culture against the North’s influence — a defense of Christianity, social order, and states’ rights.

The Lost Cause emphasized the stories of noble, chivalrous warriors — the type of people who belong on a pedestal. It presented the antebellum South as a land of gracious, cultured living. And it opposed anything that would upset the traditional racial, political, and industrial status quo. It also kindled resentment against the North over what had been lost in the war.

But the narrative of the Lost Cause omits, minimizes, or mis-remembers the most troubling aspects of the war. Professor of History of the Civil War at the University of Virginia Caroline E. Janney calls the Lost Cause as “an important example of public memory, one in which nostalgia for the Confederate past is accompanied by a collective forgetting of the horrors of slavery.”

Henry Louis Gates describes the Lost Cause as “a brilliantly executed propaganda campaign that successfully changed the narrative of the cause of the Civil War from freeing the slaves to preserving states’ rights and a people’s noble way of life.”

The Lost Cause, and the appeal to southerners’ pride, proved successful to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Between 1900 and 1917, membership grew from 17,000 to 100,000. The Daughters sought to raise awareness of the Lost Cause and to preserve southern virtues by choosing textbooks for schools that best represented their version of the Civil War. But their chief focus was on the construction of Confederate monuments.

In 1907, Goodlett told the United Daughters that, in hindsight, she’d envisioned something for the organization beyond raising statues and funding memorials. She had waited for “the monument fever to abate” so the organization could take on a more important goal. The greatest monument the Daughters could build in the South, she added, “would be an educated motherhood.” But the year that Goodlett made her comments, monument fever was an all-time high and wouldn’t slow for another decade.

Today, about 700 monuments honoring the Confederacy, its soldiers and its statesmen, can be found in 31 states and D.C., though the Confederacy only incorporated 11 states. Given when almost all were built, they are not so much memorials of the 1860s as tributes of the twentieth century to honor a version of southern history that’s goal was to, as Mayor Landrieu put it, “rewrite history to hide the truth, which is that the Confederacy was on the wrong side of humanity.”

Featured image: Statue of Robert E. Lee is removed from its pedestal on May 17, 2017 (Abdazizar, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, Wikimedia Commons)

Saturday Evening Post History Minute: Using Photography to Fight Slavery

See all of our History Minute videos.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Considering History: Reunion, Juneteenth and the Meaning of the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This past weekend, after Alabama Senator Doug Jones voted for a bipartisan amendment to the annual defense authorization bill that would remove the names of Confederate officers from U.S. military installations, former Attorney General and current Senate candidate Jeff Sessions tweeted an extended critique of Jones. Arguing that “Naming U.S. bases for those who fought for the South was seen as an act of respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Sessions attacked Jones’s vote as “a profound deficit in his understanding of what it means to be AL’s Senator. [Jones] seeks to erase AL’s & America’s history and thousands of Alabamians for doing what they considered to be their duty at the time.”

That Sessions, who in the late 1980s was denied a federal judgeship due to his overtly racist views and whose full name is Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III, would endorse keeping Confederate names is no surprise. But his comments reflect more widespread and fundamental American issues, not simply the prevalence of Confederate names and memorials but also the way our collective memories have consistently framed the Civil War as a tragic conflict between white Americans — rather than as the culminating moment in the history of American slavery and a complex but crucial turning point in African-American history.

In two of my recent Considering History columns, I’ve discussed the rise and dominance of neo-Confederate narratives in the century after the Civil War: tracing the late 19th century renaming and reframing of Decoration Day as Memorial Day; and using white supremacist elements of the New Deal to illustrate the decades-long process by which, as Heather Cox Richardson has recently put it, the South won the Civil War. The proliferation of Confederate memorials and statues offers one particularly overt and potent example of that trend, which is why historian Adam Domby focuses at length on such commemorations in the opening chapter of his excellent new book The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory (2020).

Yet alongside that evolving late 19th and early 20th century neo-Confederate narrative we find another, and in some key ways even more destructive, collective vision of the Civil War: one that defines it as a tragic conflict between white Americans. Despite the central role of slavery in the war’s causes and emancipation in its turning points and outcomes, this vision focuses on the white soldiers who fought and died on both sides, as well as on the white families and communities torn apart by the war. Minimizing both the hundreds of thousands of African-American soldiers who served the Union cause and the millions of African Americans profoundly affected by its victory, this narrative instead frames the war’s shared losses and tragedies for all white Americans. And in so doing, this longstanding definition of the war’s meanings likewise, and even more crucially, contributes to an understanding that the nation’s primary goal in the post-war period was to bring white America together once more, rather than to address the significance and aftermaths of emancipation for enslaved African Americans.

In the famous closing sentence of his March 1865 Second Inaugural Address, with the war not yet concluded, President Abraham Lincoln provided a clear early example of that vision:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

While Lincoln reiterated that the Union cause was right, both this sentence and his brief speech overall focus far more on the goals of healing and peace, and on the absence of malice and presence of charity toward the Confederates that could best achieve those goals.

Those post-war goals came to be part of an overarching frame of reunion, the process of bringing back together the nation that had been tragically and painfully divided by the war. So widespread were cultural depictions of that process that an entire literary genre, what scholar Nina Silber has termed “the romance of reunion,” developed in the post-war decades; these works feature Northern and Southern protagonists whose post-war romantic relationships, connections which depend in these stories on the characters downplaying the war’s horrors in favor of mutual understanding and admiration, symbolize and model the reuniting of North and South.

This frame for the post-war period as a time of reunion also entailed a particular vision of the war itself. That narrative focused on the concept of “disunion,” on the war as fundamentally defined by the tragic separation of and ultimately the connections between the Union and Confederate sides. As historian David Blight argues in his landmark study Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (2002), this “culture of reunion … emphasized the heroics of a battle between noble men of the Blue and the Gray.” We see the legacy of that emphasis in Jeff Sessions’ argument for “respect and reconciliation towards those who were called to duty by the States,” Confederate as well as Union.

This vision of heroism and sacrifice on both sides has come to dominate cultural representations of the Civil War. Michael Shaara’s best-selling and Pulitzer-winning historical novel The Killer Angels (1974), adapted into the popular Hollywood film Gettysburg (1993), depicts the humanity and heroism of Union and Confederate officers at the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. Even more influential has been Ken Burns’ nine-part documentary The Civil War (1990), the centerpiece of which is the use of private letters and diaries to depict the perspectives and voices of ordinary soldiers on both sides of the conflict. These and other texts have helped create and amplify an enduring narrative of brother fighting brother, of two divided yet parallel American communities.

Yet more than 180,000 of the Union soldiers were African American, of course, a sizeable cohort (comprising 10 percent of the Union army and 25 percent of its navy) all too often forgotten in these collective memories of the war. But the bigger problem with this vision of the Civil War is that it has minimized, if not indeed ignored, what Blight calls “the moral crusades over slavery that ignited the war … and the promise of emancipation that emerged from the war.” Which is to say, our collective memories of a war can focus not only on the experience of fighting it, but also and especially on the war’s overarching purposes and meanings — hence our narratives of World War II, for example, as a battle to halt Nazi aggression and stop the Holocaust. What would it mean to define the Civil War not as a tragic conflict between divided Northern and Southern states, but as a necessary and crucial final step in the long, even more tragic history of slavery in America?

One thing that reframing would mean is that the abolition of slavery would become not just an element or effect of the Civil War, but the war’s essential through-line and meaning. On June 19th, 1865, a community of enslaved African Americans in Texas learned that the war was over and slavery had been abolished; that date has been known ever since as Juneteenth, a symbolic anniversary of emancipation celebrated as a holiday within the African-American community. But over the more than 150 years since, Juneteenth has never received any national or formal recognition as a holiday, much less been highlighted as symbolizing the war’s culminating and crucial event. Similarly, the 1863 events consistently emphasized by historians and in our collective memories as the turning points in the war are the early July Battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg, not the January 1 Emancipation Proclamation that represented the first step toward comprehensive abolition.

If the Civil War had been consistently defined in the immediate post-war period through this narrative of slavery and emancipation, it would have likely been more difficult for the nation to so thoroughly forget and fail its African-American citizens. An 1877 editorial in the progressive magazine The Nation opined that, with the end of Reconstruction, “the negro will disappear from the field of national politics. Henceforth the nation, as a nation, will have nothing more to do with him.” Such an argument depended on the narratives of disunion and reunion, on a vision of both the war and the post-war period that emphasized white Americans coming back together after a tragic separation, rather than African Americans participating in and emerging out of a war of emancipation and abolition.

We can’t change what happened after the Civil War, nor the events of the subsequent 150 years. But we can shift both our narratives of those events and our 21st century conversations about the war. And if we remember the war as both the culmination of the tragic history of slavery and a fraught but crucial turning point toward all that has followed for African Americans, if we commemorate emancipation as the war’s fundamental purpose and Juneteenth as its defining memorial, we will be able not only to reframe the Civil War’s essential meanings, but also to move away from the narratives that have made collective Confederate memory so possible and potent.

Featured image: African Americans celebrating Juneteenth in 1900 (The Portal to Texas History Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

The Campaign That Sold the Klan

It was one of the greatest — and most disturbing — success stories of the 1920s. In just five years, the Ku Klux Klan grew its membership from a few thousand to five million. What had been an organization principally of rural white southerners in the 1860s now included among its members doctors, lawyers, and professors in both northern and southern states. How did they do it? Like any modern organization: they launched a marketing campaign.

The Klan had begun as a fraternal order of former Confederate soldiers who terrorized freed slaves and members of the state governments implementing Reconstruction. But when Reconstruction was dismantled, the Klan melted away.

By 1915, the Klan had just one member: William Joseph Simmons. He was inspired to revive the organization after watching D. W. Griffith’s film, Birth of a Nation, which portrayed Klansmen as heroes.

To Simmons, 1915 seemed right for the Klan’s return. Many southerners were angered by progressive policies that were expanding the federal government and supporting civil rights for minorities. Also, many resented the flood of immigrants and feared foreign cultures would destroy what they considered “traditional American values.”

Simmons felt the country would be receptive to an organization pledged to white nationalism. On Thanksgiving Eve, 1915, atop Stone Mountain near Atlanta, Simmons swore 15 candidates into the revived Klan. After they repeated the oath, he set a large cross on fire. It was a bit of stagecraft dreamed up from Birth of a Nation that had captivated Simmons, and it soon became a Klan tradition.

But something was missing. Recruitment was slow. In five years, Simmons had added only 5,000 members.

Then he met Mary Tyler and Edward Clarke, professional fundraisers who saw potential in the Klan, particularly when Simmons offered them 80 percent of the profits from dues. In June 1920, they became the brains behind the Klan’s national marketing campaign.

The timing for a racist organization was better than it had been five years earlier. There was a new defiance among black Army veterans, now returning to the South from the war. Having served their country, they were unwilling to reprise any subservient role in their communities. Major race riots had already erupted in several cities.

But Clarke and Tyler realized that racism wasn’t enough. Not every part of America was as interested in suppressing black Americans and protecting white power. The Klan couldn’t grow unless it reached a broader audience.

So Clarke and Tyler divided the country in eight regions and sent out 1,000 agents to identify the focus of bigotry and fear in their assigned areas: labor-union organizers and communists in the industrial north, Asians on the west coast, Jews and Catholics almost anywhere.

They began to expand the Klan’s mission, stirring hatred against these groups.

The two also tapped into Americans’ anger at accelerated social change. They wanted to channel the disapproval of the media that mocked tradition, the rebellious attitude of young people, the immodest behavior of women, and, of course, jazz.

Having relatively few adherents in cities, the Klan adopted several attitudes popular in rural areas. They helped enforce Prohibition and they denounced motion pictures.

Almost everywhere they found a public yearning for a golden past, where they remembered an America free of foreign influences. Millions were drawn to the Klan’s policy of “America for Americans” as well as its sometimes violent enforcement of fundamentalist Protestant values.

Many members would never have supported the beatings, tar-and-featherings, murders, and kidnappings committed by other Klansmen. They believed in the Klan was a patriotic, God-fearing organization that revered traditional values. To them, it was simply a fraternal organization, a good place to enjoy white privilege, and maybe do some business networking.

Tyler realized that American women were another promising market. “The Klan stands for the things women hold most dear,” she told the New York Times in 1921. She developed a women’s Klan that eventually claimed 500,000 members, who hosted picnics and attended cross burnings.

They launched a modern media campaign for Simmons, lining up interviews with reporters. Suddenly the Klan’s message was reaching whole new parts of the country. Within a few months, membership had grown 2,000 percent.

Meanwhile their agents were recruiting members in every part of the country. About half of every $10 initiation fee they collected was forwarded to the national office in Atlanta, most of it flowing into the pockets of Clarke and Tyler.

In addition, they were getting a kickback on the sale of official white robes, charging $6.50 for robes that had cost them $3.28. Sensing even greater profits, they began churning out various Klan publications for members. As another sideline, they managed real estate on Klan-owned properties. Within a year, Clarke and Tyler had taken in over a million dollars.

It had been an illegal, covert organization in the Reconstruction era. But in 1925, over 50,000 Klansmen marched boldly through Washington D.C. And, contrary to tradition, not a single one wore a mask.

Not only had the Klan gained social acceptance, it held political power. Klan-backed candidates held office in city and state governments across America, where they protected the Klan’s interests. In Indiana, Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson could even claim, with good reason, “I am the law.”

The Klan might have seemed unstoppable, but the end came soon afterward as it was rocked by several scandals. In addition, the fallout from several investigations was bringing to light the true work of the Klan.

The New York World’s investigation revealed that, in 1921, the Klan was responsible for four murders, a mutilation, 41 floggings, 27 tar-and-featherings, five kidnappings, and 43 threats and warnings to leave town. Civic groups started posting the Klan’s membership lists publicly, and the NAACP led a successful public education campaign about the abuses of the Klan.

One of the scandals took down Tyler. She and Clarke were planning to oust Simmons and take over the Klan’s leadership when they were arrested in a “house of ill repute.” Police discovered them conducting an affair despite being married to others — while in possession of bootleg alcohol. Klan members were outraged, especially when they discovered Tyler, a woman, had been the force behind the Klan’s rapid growth.

She was accused of embezzlement and forced out of the Klan in 1922.

That same year, the FBI was requested to investigate the Klan control of northern Louisiana. The complaint said members had already tortured and killed two men who had opposed the organization. The FBI focused its efforts on Clarke, who had been able to remain an officer in the Klan and was now taking $8 out of every $10 initiation fee.

Unable to convict Clarke on any existing law, he was charged with violating the Mann Act when he drove his mistress across a state line. He, too, was forced from the Klan and moved out of the country to avoid prosecution.

The Klan’s membership started declining rapidly, from its peak of five million members in 1925 to 30,000 in 1930. It reached a low of 3,000 in 2015. Recently, Klan membership has started to pick back up again. There’s been no official word on who is handling their marketing.

Featured image: A flyer advertising a Klan event at the Texas State Fair, 1923 (The Portal to Texas History, the University of North Texas)

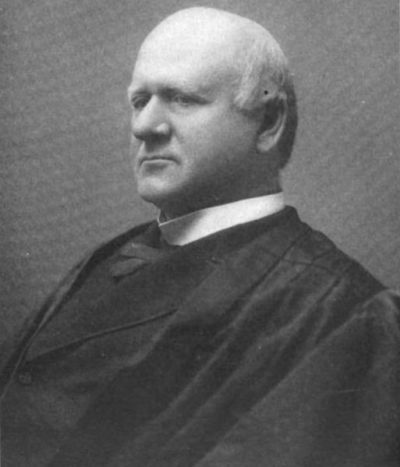

Before Brown v. Board of Education, Sweatt and McLaurin Challenged “Separate But Equal”

When it comes to controversial Supreme Court decisions, Plessy v. Ferguson remains a flashpoint. The 1896 decision perpetuated segregation if the transportation or facility in question was “equal” in quality to the thing that was serving the white population. Of course, the facilities in question were rarely equal in quality, design, or funding. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education smashed that notion in a decision that rendered segregation of public schools to be unconstitutional. However, two cases decided in 1950 laid the groundwork for Brown by challenging “separate but equal” in higher education. Those cases were Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, and their decisions were returned 70 years ago today.

Sweatt v. Painter involved Herman Marion Sweatt. Sweatt, who was black, applied to the University of Texas School of Law, but was denied admission. The rationale handed down by the University president Theophilus Painter was that the constitution of the state of Texas banned integrated education. Sweatt’s original suit received a continuation in state district court, which was a stall tactic for the school. The University of Texas then put together a law school in Houston for black students, which wasn’t even in the same city (Austin) as the original School of Law. With the support of the NAACP, Sweatt took the case to federal court on the grounds that the facilities, while separate, were in no way equal.

The Supreme Court decided in favor of Sweatt, agreeing that the facilities created for black students suffered greatly in comparison. Examples in the unanimous decision included the smaller number of faculty, the vast disparity in library size, and a variety of other facilities issues. The Court also cited the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment as the constitutional basis upon which Sweatt should be admitted.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents involved graduate programs at the University of Oklahoma. George W. McLaurin had earned a Master’s in Education from University of Kansas, but was denied the opportunity to pursue his Doctorate at Oklahoma. McLaurin sued in U.S. District Court, invoking the 14th Amendment, and won. The school admitted him, but forced him into separate facilities, even occasionally making him eat at times when white students weren’t present. McLaurin petitioned the District Court for redress, but was denied, so he took the case to the Supreme Court. In another unanimous decision that also leaned on the 14th Amendment, the Court held that the school couldn’t restrict McLaurin in that manner.

The two cases set the stage for Brown v. Board of Education four years later. Another influential case leading up to Brown was Mendez v. Westminster, which allowed the integration of Mexican-American students into the California school system. The Supreme Court Justices deciding on Brown would also invoke the 14th Amendment and unanimously vote to overturn the “separate but equal” notion that had been enshrined in Plessy.

Sweatt and McLaurin may not be as widely known, but they remain significant steps along the way toward realizing an equal vision of education in America. They set important precedents that allowed bigger decisions to be made later. 70 years on, in an America that still struggles mightily with a legacy of segregation and mistreatment, it’s important to acknowledge that the smaller victories can still bring about greater triumphs.

Featured image: Shutterstock

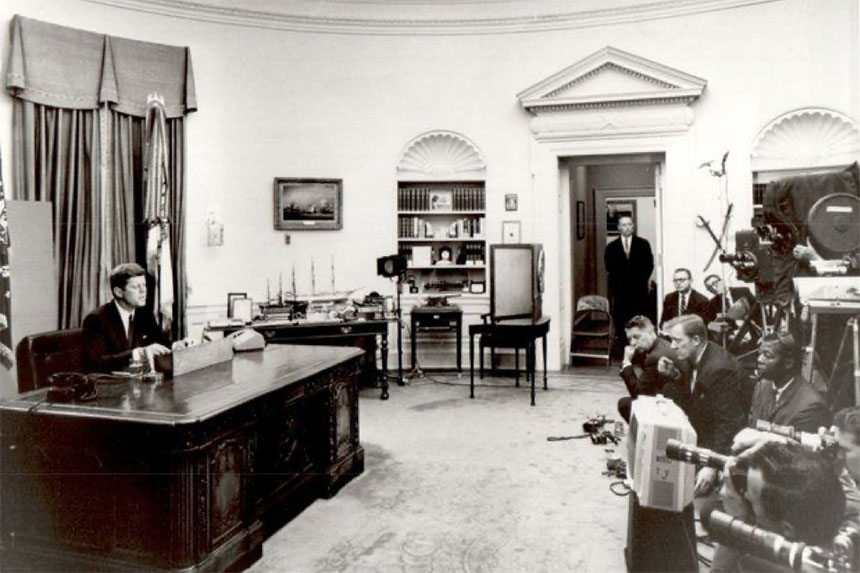

Considering History: Civil Rights, Racism, and the Question of American Progress

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On June 11, 1963, President John F. Kennedy gave a televised presidential address on the question of race and civil rights. The speech addressed specific, ongoing events: earlier that day Alabama Governor George Wallace had literally blocked two African American students, Vivian Malone and James A. Hood, from enrolling at the University of Alabama; in response Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard, after the arrival of which Wallace backed down and Malone and Hood successfully integrated the university. But Kennedy used his June 11 address and its national platform to go much further than that targeted response, proposing sweeping civil rights legislation that his administration would subsequently send to Congress.

Like Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous March on Washington speech, delivered two-and-a-half months later, Kennedy’s speech frames the events of that time through the fraught question of American progress. As Kennedy notes, “One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free.” In his speech’s opening paragraphs, King extends and deepens that point: “But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free; one hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.”

A century after the Emancipation Proclamation, America had made painfully little progress on issues of racialdiscrimination, oppression, and violence. But what about now, 57 years after Kennedy’s speech, more than half a century beyond the March on Washington? While some progress has unquestionably been made, when it comes to key issues such as white supremacist violence, voting rights, and structural inequity and inequality, America remains far too close to where it was in the summer of 1963.

The areas on which the most overt progress has been made tend to be those that were directly covered by the Civil Rights Act, the July 1964 law that resulted from Kennedy’s proposal. Institutions like schools and businesses can no longer discriminate against Americans based on their race, nor any other element of their identities (although the legal battle over discrimination based on sexual orientation continues to rage). That progress is about not only access but also equality: institutions can also no longer create separate, segregated spaces for individuals of different races, and must instead offer the same opportunities or face legal and financial penalties; in one of the most famous such cases, In 1994 Denny’s restaurants were proven to be discriminating against African-American patrons and had to pay tens of millions of dollars in settlements.

But as Kennedy’s speech acknowledges, civil rights is about more than just equality of access or opportunity, and instead represents what he calls “a moral issue … as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution”: “whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated,” whether every American can “enjoy the full and free life which all of us want.” And on a number of levels, African Americans continue to be denied the full protection of the law that would guarantee such freedom from discrimination and oppression.

Protection from racist violence remains frustratingly rare for 21st century African Americans. Some of the foundational incidents of the Civil Rights Movement featured an absence of such protection, from the lynching of Emmett Till and the sham trial that followed it to the ubiquitous sexual violence that precipitated the Montgomery bus boycott. Yet despite civil rights laws and more recent follow-ups like the 2019 anti-lynching legislation, those who commit acts of violence against African Americans still all too often escape justice. Some of those are civilians committing extra-judicial lynchings, like George Zimmerman’s 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin or the two men who killed Ahmaud Arbery in February (and the third who filmed it). But many are officers of the law, such as the police officers involved in the 698 shootings of African Americans between 2017 and March 2020 (22 percent of the 3,215 total shootings over that time; in another 629 shootings the victim’s race was unreported, so the percentage is likely higher still). Many of those citizens and officers were never charged with a crime; of those few who have been indicted, the vast majority were (like George Zimmerman) acquitted on all counts.

One of the principal means through which such legal injustices can be challenged is by voting in new officials, and the Civil Rights Act’s 1965 counterpart, the Voting Rights Act, extended federal voting protections to African Americans. But in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder decision, the Supreme Court ruled that key Voting Rights Act protections were unconstitutional, adding that the country “has changed” and that such protections are thus no longer as necessary as they were in 1965. In the half-decade since the decision, that opinion has been proven entirely incorrect, as countless measures have been enacted that work purposefully and effectively to limit and deny the vote for African Americans and other communities of color. The proponents of such measures, which often closely mirror pre-Voting Rights Act practices such as poll taxes and “literary clauses,” have consistently admitted that suppressing the vote among those particular American communities is their goal.

While of course African Americans want the same legal and democratic rights as all Americans, their ultimate goals are even more fundamental and deep-seated: as James Baldwin put it in a 1968 speech, “I simply want to be able to raise my children in peace, and arrive at my own maturity in my own way in peace.” But systemic, structural inequities and inequalities make those goals far less achievable for African Americans than their white fellow citizens. Take two elements of my seemingly progressive home state of Massachusetts, for example. Massachusetts’ public schools are significantly more racially segregated in the 2010s than they were a few decades earlier, with the schools with the highest percentage of students of color receiving over $1000 less in annual funding per pupil. And not coincidentally, a groundbreaking 2017 investigative series by the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team found the median net worth for an African-American family in Boston to be $8 (that’s not a typo, it’s 8 dollars), compared to a median net worth of $247,500 for white families.

Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These are the inalienable rights that the Declaration of Independence identifies as core values of the United States of America. In June 1963, the proposed Civil Rights Act (like the Civil Rights Movement) sought to better protect those rights and thus make them more genuinely attainable for African Americans. As of June 2020, it remains an open and crucial question whether the nation has progressed closer to that promise, and what we must do to ensure real progress from here.

Featured image: Lyndon Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act (Wikimedia Commons / LBJ Library / Public Domain)

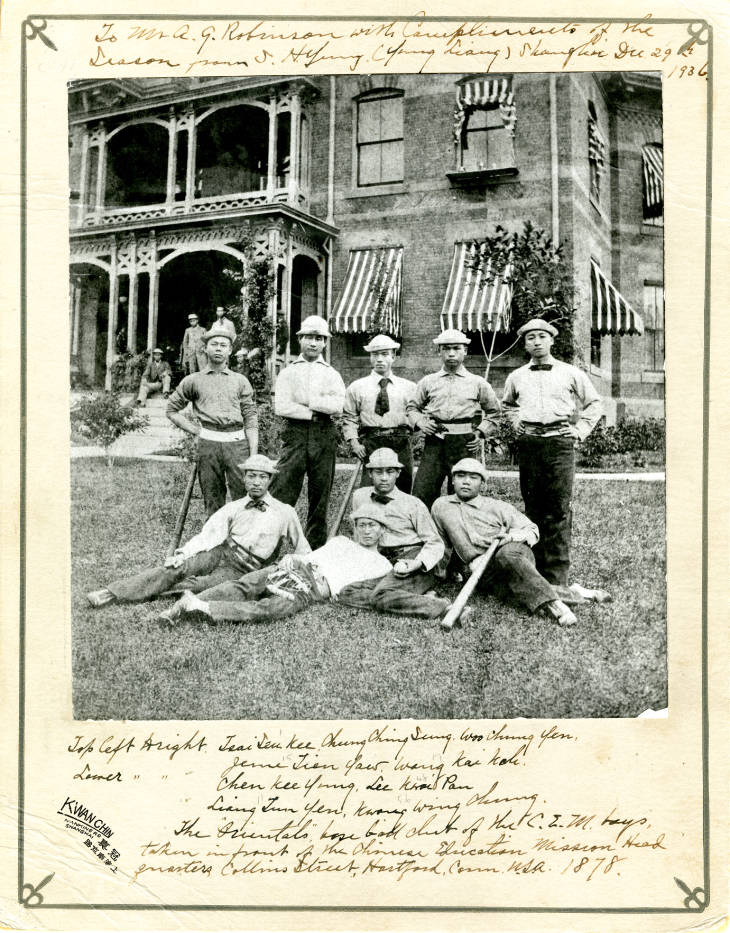

Considering History: Baseball, Chinese Americans, and the Worst and Best of America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In honor of Asian and Pacific Islander American Heritage Month, PBS is airing this week a compelling and vital new five-part documentary, Asian Americans. This examination of the longstanding, multi-faceted histories of the Asian-American community (across many different nationalities and cultures) could not come at a more important moment, as xenophobic and racist associations of COVID-19 with China have led to a dramatic spike in harassment and hate crimes targeting Asian Americans.

Such prejudice and violence are driven by equally longstanding collective narratives of Asian Americans not only as carriers of disease, but also as fundamentally outside of and foreign to “American” identity. Even a prominently progressive American figure like Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote, as part of his famous dissent to the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision, that Chinese Americans were “a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States” (contrasting that idea with his support for African-American equality under the law). In a public lecture two years later, he went even further, arguing that “this is a race utterly foreign to us and never will assimilate with us.”

In that late 19th century era of Chinese-American exclusion, such racist and xenophobic sentiments were given voice not only in governmental and legal documents, but also in violent gatherings of white supremacist protesters and agitators. Yet in one of the most prominent sites for these angry and divisive gatherings, a sandlot in California, we can also find a far more inclusive and inspiring vision.

As anti-Chinese sentiment became a dominant social and political perspective in the 1870s, one of its leading proponents was an Irish-American businessman, labor activist, and demagogue named Denis Kearney (1847-1907). Born in County Cork, Ireland, Kearney left home at the age of 11 and sailed the globe for a decade on clipper ships, working his way up from cabin boy to first mate before finally settling in the U.S. in 1868. Over the next decade, he married a fellow Irish immigrant (Mary Ann Leary), started a family, and established a successful delivery business in San Francisco, but it was his evolving labor and anti-immigration activism that would earn him national attention.

Kearney’s activism began with a focus on labor, including specific opposition to a city monopoly on hauling and broader support for workers’ rights; to that end he helped found in 1877 a new political party, the Workingmen’s Party of California. But he became especially famous for his fiery rhetoric, often delivered at an outdoor San Francisco space known as “The Sandlot.” In speeches that often lasted as long as two hours, delivered to thousands of angry workingmen, Kearney attacked opposition politicians, advocated for violence if their demands were not met, and, more and more over time, identified Chinese Americans as the community’s true adversary (leading the era’s anti-Chinese narratives to be frequently called “Kearneyism” and “Sandlotism”).