The child who sets out to be a career artist and skips the “starving artist” phase has a rare story indeed. But Mead Schaeffer’s ability was undeniable, his talents easily promoted. Born July 15th, 1898 to Presbyterian pastor Charles and his wife, Minnie, Mead grew up knowing he wanted a career in art. His work brought fame and fortune alongside a lifelong friendship with another American master, Norman Rockwell.

Born in Freedom Plains, New York, the Schaeffer family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts when Mead was a little boy. He graduated high school in 1917, and moved to Brooklyn, New York shortly after to attend the Pratt Institute.

At the Pratt Institute, Schaeffer studied under Harvey Dunn and Charles Chapman. His two mentors had started their own school, the Leonis School of Illustration, in 1915. The school’s philosophy followed that of their own teacher, the famed instructor Howard Pyle. Experiencing various art groups in the city, Schaeffer became acquainted with Dean Cornwell. Mead’s relationship with Cornwell led to Schaeffer’s first jobs producing illustrations for smaller magazines and publications. He graduated at the top of his class, already a working artist, in 1920.

Throughout Mead Schaeffer’s 20s, he worked for Dodd, Mead & Company, a publishing house for classic literature. Schaeffer provided illustrations for sixteen prominent works including The Count of Monte Cristo, Les Miserables, Typee, and Moby Dick.

On September 17th, 1921, Schaeffer married his wife, Elizabeth. They had two daughters, Consolle and Patricia. New York City soon became too cramped for the family. They moved to Rye, NY and then the artists’ colony at New Rochelle, NY where the artist first met Norman Rockwell. He later moved to Arlington, Vermont where he kept a studio in an old barn as Rockwell’s next-door neighbor.

Schaeffer was introduced to Saturday Evening Post editor Ben Hibbs through Rockwell. Schaeffer’s relationship with the Post resulted in a career spanning thirty years and 46 cover illustrations. Schaeffer became most famous for chronicling the military with authenticity.

Rockwell and Schaeffer set out to pitch an idea to the government about ads for war bonds, but they were rejected. Hibbs picked up the idea and sponsored their work through The Saturday Evening Post. Schaeffer spent 1942 to 1944 as a war correspondent. He flew in planes, rode in submarines, and toured with soldiers to get a feel for the soldiers’ experiences in World War II. His collection, including 16 Saturday Evening Post covers, went on a tour to 92 cities in the United States and Canada. The tour’s purpose was to drum up sales for war bonds.

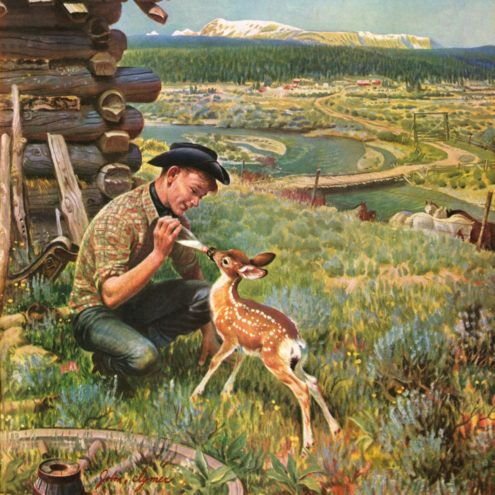

After the war, in the summer and fall of 1947, the Schaeffers and the Rockwells took a two and a half month family vacation to the American West. The families were so close many works by both artists contain the other’s children as models. Schaeffer’s wife often took dozens of photographs from all angles while the artist studied the scene. After the trip, the artist studied his wife’s photographs and incorporated their view into his work. From all of his sketches and studies, the trip provided only six Post covers.

Over the course of a 30-year career, Schaeffer provided 5,000 illustrations to books, magazines, and advertisements. His last cover for the Post was December 26th, 1953. He spent much of his retirement sketching and fly-fishing, often taking trips to Puerto Rico. By the end of his career, Schaeffer had worked for The American, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan, Scribners, Home Companion, Ladie’s Home Journal, Redbook, McCall’s, St. Nichol’s Century Magazine, and of course, The Saturday Evening Post.

He died of a heart attack on November 6th, 1980 while at lunch with his contemporaries at the Society of Illustrators in Manhattan. Today his works are on display at the USAA in San Antonio, Texas.

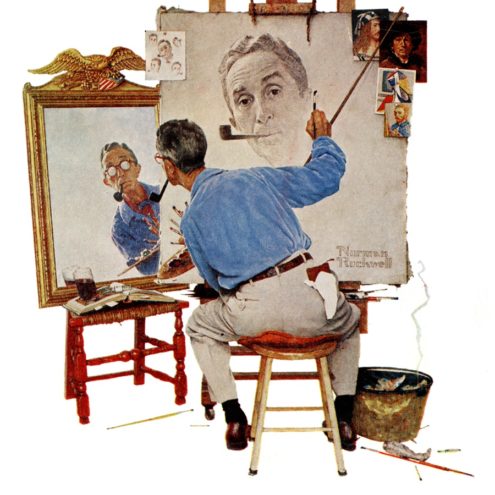

(Photo: Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©Norman Rockwell Family Agency.)